Which of your works do you like most and why?

I consider Medvědí román to be the most important, though I actually prefer Brněnské povídky. All the essentials were revealed to me in Medvědí román, my way of writing, i.e. the status of the narrator, who is also actually one of the characters, so he can enter the narrative, as well as the narrative game and the awareness that narrative for me is not just a depiction of reality, but a reflection of reality through stories. I like Brněnské povídky most, because short stories are my favourite genre even as a reader: Bunin, Babel, Borges, and here Vyskočil, Hrabal and the like. Of Kundera’s work I most like Směšné lásky and Knihu smíchu a zapomnění, which are also stories actually. As an author I like short stories most of all, because I feel I’m more of a sprinter than a marathon runner, and I only write novels when I find a particular plot simply doesn’t fit into a short story.

What are you working on at present?

On the journalistic flea market (essays, feuilletons and so forth) and a second book of Brno tales.

What would you like to write and publish next?

Apart from the journalistic work and the second book of Brno tales there is another novel, whose subject and plot I do already know.

Which work do you regard as your most successful with regard to criticism, literary awards, readers’ responses, number of copies sold and number of translations, or responses from abroad?

The novel Uprostřed nocí zpěv, published by Gallimard and Rowohlt, two of the most prestigious European publishers.

Where do you think your works are best understood?

In the German-speaking world and surprisingly in Spain.

How do you write – easily, quickly, by hand, on the computer?

I write slowly – first version by hand and the second one on the computer.

How and why did you become a writer?

Narro, ergo sum. Even as a boy I used to be a popular story-teller, and I enjoy turning reality into fantasy.

Your stories sometimes have a dream-like quality. Do dreams play a role in your narrative art? Do they ever inspire you?

I’d say they do, and it’s happened several times now that a story I didn’t have a clue what to do with, a story that had got stuck, was “written out to the end” in a dream.

How would you feel if you ever found one of your stories in a science-fiction anthology? Are you interested in science fiction and fantasy here and abroad?

I’d be very pleased. I’m a keen sci-fi reader, but only the classics, like Bradbury, Clarke and Asimov.

Linguistically your stories often have a distinctive Brno touch to them. Do you actually think in Brno “Hantec” dialect?

No, I don’t think in Hantec. Nowadays that’s just artificial folklore, though it was still alive when I was a boy. It no longer interests me, apart from just a few words that have slipped into my literary vocabulary for good, just like a few Slovak words have, for example.

How do you feel when you are in Prague? Are you able to write when you are there?

I can’t write anything in or about Prague.

What do you say to those who feel there is some “escapism” in your stories?

Well, I actually feel my short stories and novels are condensed from reality, as it were. I went through a dozen different trades in the days when I was a forbidden author, and when I say trades I mean labouring at plants of all kinds, and after my father emigrated I experienced all kinds of interesting traumas (that is, they strike me as interesting now from the literary viewpoint), so quite unwillingly I have lived an adventurous life, which I make copious use of in my stories.

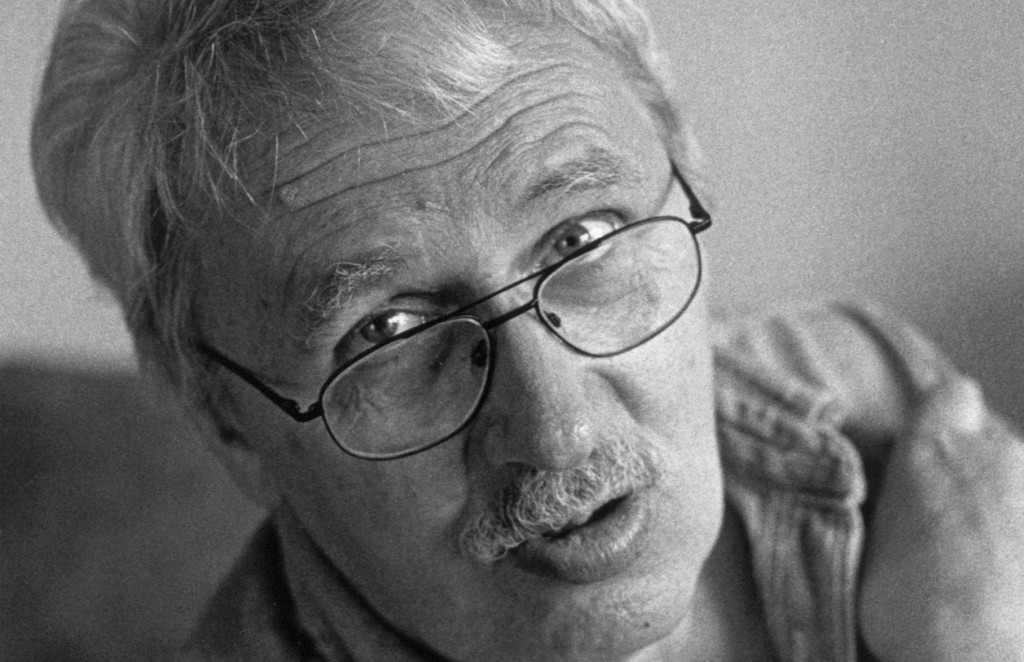

Interviewed by Melvyn Clarke