This summary is neither an in-depth analysis nor an exhaustive list of the major contemporary poetics, trends, poets, anthologies and poems aimed at specialists in Czech literature. It sets out to describe the main trends in contemporary Czech poetry in a straightforward manner, without recourse to theoretical terminology or even a strict definition of the word “contemporary” (roughly from 1989 to the present), and will attempt to suggest similarities and affinities in the methods of poetic expression employed by the poets who have been selected.

General features of contemporary Czech poetry

In terms of the productivity of authors and the number of contemporary poetry titles published, this area of literature has been faring surprisingly well. However, as is true elsewhere in the world, large numbers of books do not necessarily mean large numbers of readers, let alone sales. However, in comparison with the 1990s, when Czech poetry was in decline and people were sceptical about its very chances of survival, it now has a very stable, rich, productive and varied “creative base”. There is also no shortage of literary criticism, though this tends to take the form of sporadic reviews rather than sustained critical attention. Czech poetry receives regular publicity through selected radio programmes, series of authors’ readings presented in various ways, poetry festivals, competitions and prizes, and most importantly, literary journals, both printed (Tvar, Host, Souvislosti, Psí víno, A2, H_aluze, Pandora, Aluze, Revue Protimluv, Revolver Revue) and electronic, as well as literary websites, specialist blogs, Facebook pages (for analysis and a summary of digital Czech literature, see studies by Karel Piorecký, e.g. here), and niche publishers and editions. It is rare, though, for new poetry collections to be translated from Czech into foreign languages and vice versa.

Host magazine

However, as the Czech poetry scene becomes more fully developed (poets know each other, follow each other’s careers and read each other’s work), there is a danger of it becoming insular and rather unwelcoming (some people would go as far as to describe it as “toxic to humans”), as it constantly feeds off petty or more serious internal conflicts and animosities, often of a personal nature. Occasionally these explicit or hinted-at rivalries, whether non-programmatic or deliberately designed to court controversy, may result in a constructive polemic; mostly, however, they are unproductive if not downright destructive and do not contribute to any creative development or help to form a new style. The inaccessibility of the poetry scene makes it relatively difficult to “establish” oneself as a poet and be accepted by “colleagues/them”, something which had previously been associated with a standoffish attitude to young “beginner” poets, and with poets from the so-called regions being made to feel marginalized and unsophisticated. Now it is clear that this notional division between the centre of poetry (Prague?) and the periphery (the regions) is neither meaningful nor justifiable. In fact, it has been replaced by a paradoxical willingness to publish almost anything, including poetry of dubious quality.

In other words, contemporary Czech poetry is partly defined by the way that the poetry scene is organized – it is shaped by lively literary activity, as well as by its limitations, by the need for controversy and by the policies of publishers and grant bodies. The “marginal” status of poetry, or its existence on the periphery of readers’ interest, is seen as proof of its imagined “elitism” or complexity, which still stigmatizes this art form today. This is strongly qualified in the Czech Republic by the energy of the poetry community, in particular the activities, mutual support and friendship of authors mainly in their 30s, whose commitment to “the poetry cause” is huge and greatly contributes towards raising its profile (albeit only among the initiated) and putting it on an equal footing with other, more accessible forms of art. It seems that the willingness to resign oneself to having a small readership disproportionate to the large number of poetry collections being published prevails over any clumsy attempts to promote poetry using various methods, in particular by combining it with more attractive or “accepted” art forms in order to bring it to the attention of the general readership or culture-loving public. Apparently that 1% of the Czech population which “consumes poetry” is enough, as is the laughably outdated form of the printed poetic text, regardless of the fact that poetry is now “trendy”, just like home cooking.

The role of poetry is also increasingly being consolidated and highlighted at cultural events focusing mainly on other art forms, particularly music festivals (Colours of Ostrava, Štěrkovna) and well-attended series of poetry readings organized as part of literary festivals or around traditional literary cafés (Fra in Prague, Skleněná louka in Brno, the Les absinth club in Ostrava, etc.). An important role in raising the profile of poets’ work is also played by poetry awards, including the State Prize for Literature, the Jiří Orten Award and the Magnesia Litera for Poetry, as well as the poetry competitions Orten’s Kutná Hora, Václav Hrabět’s Hořovice, the Vladimír Vokolek Literary Award, the František Halas Literary Award in Kunštát, etc.

A reading at café Fra. Photograph: Ondřej Lipár/Fra.

There is a special character and perhaps also a discernible poetic to the “circles” of poets around small and large publishers of contemporary Czech poetry (Fra, Perplex, Dauphin, dybbuk, Host, editions from the journal H_aluze) and individual literary periodicals.

The poets grouped around the literary websites (Totem, Písmák etc.) are a chapter in their own right. In the world of the website, anyone can set up their own nick (an author’s avatar) and anonymously publish their texts, which can then be assessed and discussed by other registered users. The quality varies widely due to the quantity of work published each day (almost half a million texts have been published on the Písmák website since it began). In retrospect, however, it is clear that for writers born in the 1970s and 1980s, literary websites had a role to play during the early phase of their creative development – particularly in forming a critical basis for their work and in their search for a distinctive poetic voice amongst the deluge of instant poetics.

The oldest and largest literary website, www.pismak.cz, was established in 1997, so it is now in its 20th year. The second largest, www.totem.cz, was established just two years later. Gradually, they were joined by a number of others, including Literra, Blueworld, Epika and Saspi. For a decade, the phenomenon of literary websites was of little interest to academics and critics. This all changed in 2008 when Karel Piorecký published an article in the fortnightly journal Tvar called Where the Present Begins (Kde začíná současnost, 2008/no. 20), in which he attempted to describe this poetry community for the first time.

* * *

It may be a sweeping statement, but it would seem that traditional lyric poetry, in all of its guises, is on the decline in favour of expansive, prose-style narrative epics. Contemporary Czech poetry is not characterized by humour and playfulness, nor by long poems or lengthy poetic compositions, even though some poets are clearly attempting them. Similarly, Czech poetry no longer places such an emphasis on romantic and erotic poetry, which is part of the lyrical tradition (notably Jitka Srbová, Jiří Dynka, J. H. Krchovský, Svatava Antošová, Adam Borzič, Elsa Aids, Simona Racková, Tereza Riedelbauchová; occasionally Kamil Bouška, Jakub Řehák, Milan Ohnisko and Ondřej Hanus). Instead it would appear that there is an established place in Czech poetry for nature lyricism and poetry with a sense of place (locality/city/region) – Radek Štěpánek, Petr Maděra, Pavel Kolmačka, Vít Janota, Ondřej Hanus and many others.

Contemporary Czech poets do not usually follow current international trends, and when they do it tends to be the more experimental poets. In terms of the basis, spirit and focus of their work, Slovak and Polish poets along with some members of the Anglo-American poetic tradition have most in common with Czech poetry. However, there continue to be deliberate creative responses to the work of the greatest poets in Czech history – today we can find traces, allusions and echoes, but also obvious imitation, of a tradition that goes back to Reynek, Skácel and Holan; of the poets from the middle generation, the most emulated is Petr Hruška, followed by J. H. Krchovský, Miloslav Topinka, Petr Král, Ivan Wernisch, Petr Borkovec, Jaromír Typlt and a few others. Karel Kryl and Filip Topol are still influential in the sphere of songwriting, although new, original poetic texts set to music by professionals are surprisingly rare. In recent years, a good many authors from the younger generation have directly reflected on the present day, both in terms of social criticism (“engaged poetry”, sensitive towards current events in society, which it strives to be an active part of) and intimate–empirical work (modern-day civilism).

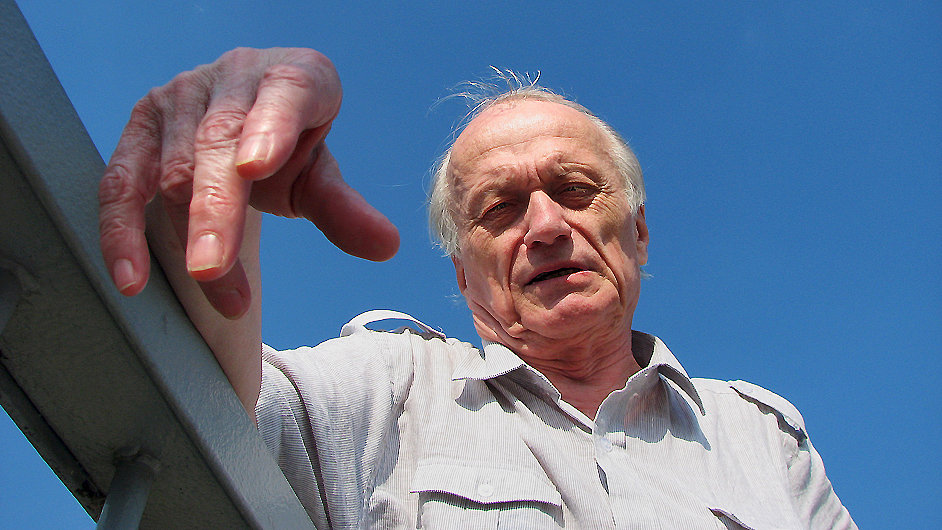

Petr Král. Photograph: HTO/Wikpedia.

Generational differences do not play a particularly important role in contemporary Czech poetry either, and it cannot be said that poets born in a particular decade consistently have a distinctive poetic, even though it is possible to spot certain similarities between members of the generations mentioned below, most notably with the generation that began publishing work in the 1990s, and the generation of thirtysomethings who brought out their debut works in the first decade of the new millennium. However, the poetry scene does begin to fragment at the most general level when it comes to the overall view of the meaning and purpose of poetry: at one extreme lies the inward conviction of poetry’s elite, supreme status and absolute autonomy, while at the other is the outward belief in the power of poetry as a way of animating and stimulating society (“engaged poetry”). However, advocates of poetic autonomy dismiss this kind of “role” as an encumbering and profaning of poetry, akin to the notorious “mission” which poetry was assigned during the 1950s and Normalization.

Nevertheless, it has to be said that there is something fairly distinctive about the creative generation born in the 1980s and especially during the 1970s, as well as the highly respected group of authors who were born in the 1960s, made their debuts in the 1990s and were labelled the “incubator of (future) Czech poetry”. The style of the “nineties mainstream”, which also crossed over into the noughties, was characterized with a touch of hyperbole by Petr Boháč (Tvar, 2007, no. 20): “It wouldn’t be hard to sit down and write a collection of poetry in the style of contemporary everydayness. If I really went for it, I could have it finished in five days. The structure of the poems is fairly obvious: someone goes to a window, there’s a storm or the sun is shining or it’s muggy, there has to be some kind of poetically depicted memory, but in one verse at the most, and finally it has to have a wider message which reverberates in the silence. Like I say, five days, five hours and five minutes – you could probably announce a competition for it. Then you could send it to Balaštík [the editor-in-chief] at Host and there’d be another poetry collection by a promising new poet.” Only a few names remain outside of this stream, the most important being Božena Správcová, Vít Kremlička, Petr Hrbáč and Jaromír Typlt.

Among the most significant collections published at the turn of the millennium were those written by the poets Kateřina Rudčenková, Marie and Irena Šťastná, Jitka Srbová, Viktorie Rybáková, Simona Martínková and Janele z Liků.

Kateřina Rudčenková. Photograph: Pavel Horák/Wikipedia.

From the “generation of lone runners” (a term coined by literary critic and academic Petr A. Bílek) who made their debut in the 1980s (Sylva Fischerová, Miroslav Huptych, Svatava Antošová, Vít Slíva and Lubor Kasal) and did not adhere to a single style of poetry or even a manifesto (like all of the generations which followed, including the surrealists, whose methodological orthodoxy is authenticated by members using an obscure key), most of its “members” continue to publish poetry regularly.

Therefore, in the Czech Republic, with a few exceptions (groups loosely associated with the literary journals Psí víno, H_aluze and Weles), the main creative force is individuals rather than trends/schools/streams in poetry. In addition, it would appear that poetry manifestos, which were still quite numerous in the 1990s (Borkovec, Typlt, Reiner), are no longer in vogue (one exception is the Fantasía group, although they no longer publish jointly). Respected poets from the middle generation are working alongside numerous enthusiastic creative poets from the younger generation and the still-active older generation, i.e. the generation of living legends, poets born in the 1930s and 1940s (Miloslav Topinka, Petr Král, Jiří Kuběna and Karel Šiktanc). With a few exceptions, surprisingly little of the diversification within the poetry community comes from attempts to follow on from the trends, schools, streams and traditions of 20th-century poetry.

These exceptions include the surrealist and surrealist-influenced poets (František Dryje, Kateřina Piňosová, Bruno Solařík, Roman Telerovský etc.), who make up a strong, distinctive group with its own forum in the form of a journal (the review Analogon) which bears this label. However, there are creative individuals within this group who use similar principles of an open imagination and free association (Petra Strá, Zuzana Lazarová, Jakub Řehák, Pavel Ctibor, and most recently Ondřej Hanus). There are only a few representatives of poetry based on imagination, fantasy, myth and legend, which is related to surrealism and appears more intermittently within poems or collections (Adam Borzič, Božena Správcová, Lubor Kasal, Bogdan Trojak, Ivan Wernisch and Miroslav Černý). There are other authors who favour personal, family or ancestral myths (Janele z Liků, Josef Mlejnek, Martin Poch etc.).

In addition to the surrealist poetic, there is also a relatively large number of collections of civilist poetry, though the poets do not form a homogenous group. Intentionally or unintentionally, they are influenced by the work of Group 42 (Jiří Kolář, Ivan Blatný, Jan Hanč), and they are linked to empiricism and the everyday with their images of the city, night walks, the de-poetization of poetic language, i.e. something more akin to the style of a news report, the use of the language of the street, the heightened importance of the mundane, and the predominance of free verse – something which is very common in contemporary Czech poetry in general. This very strong poetry “group” of like-minded poets (among the most respected are Petr Hruška, Petr Borkovec, Milan Děžinský, Petr Halmay, Štěpán Nosek, Vít Janota and Dan Jedlička, as well as Pavel Novotný for his language experimentation) is perhaps undermined by the descriptiveness or banalization of its themes, uniformity and interior monotony, and difficulties associated with attempts to link a poetically mediated version of the everyday with a symbolic and metaphysical “wider message”; this is, of course, the criticism levelled at it by its opponents and detractors, criticism which should really be directed at the imitators (“followers”) who produce a watered-down version of this style, rather than its leading representatives.

Some other trends in poetry have persisted in a more sketchy, unsystematic manner within specific anthologies or individual poems by authors who have not been clearly “labelled” and are not comfortable with these stylistic pigeonholes (neo-decadence, expressionism, romanticism – Bohdan Chlíbec, J. H. Krchovský, Jaroslav Pížl, Luděk Marks; dadaism, absurdity and parody have virtually disappeared – Božena Správcová, Lubor Kasal, Ivan Wernisch, Marian Palla; echoes of the underground – Vratislav Brabenec; and the Beatnik or rock-rebel style – Karel Urianek, Václav Böhmsche, Daniel Hradecký, Milan Kozelka).

Like the civilist poets, the experimental authors do not form a cohesive stylistic/thematic group apart from their numerous personal friendships; their platform, although this is never openly admitted and is sometimes explicitly rejected, is the journal Psí víno. Alongside the young experimenters who welcome conceptual tendencies and marginal artistic disciplines, and who follow similar trends in contemporary European poetry, there is the generation of poets from the 1970s who associate themselves with the experimental fashions of the 1960s (Jaromír Typlt, Pavel Novotný, Michal Šanda, Radek Fridrich and Robert Janda) and the avant-garde, or are even a part of it (Ladislav Nebeský, Miloslav Topinka, Jiří Gold and until recently Bohumila Grögerová). Then there are the lone artists who blur the lines between different art forms (literature, theatre, music, performance, visual and fine art), for example, Jana Orlová and the physical poet Petr Váša; or who place a substantial, strongly rational emphasis on “newness”, interdisciplinarity, multigenre or multimedia forms (Ondřej Buddeus), i.e. an approach guided by the intellect and appealing to multiple senses. Contemporary Czech poetry also includes posthumous publications and works by formerly unknown or inaccessible authors of experimental poetry from the 1960s (Josef Honys, Vladimír Burda and Zdeněk Barborka). However, today’s experimenters make use of different artistic approaches, with linguistic and stylistic innovation forming only a part of this.

An increasingly large section of Czech poetry is made up of works which are time-specific, incidental, socially and politically engaged and critical, focusing on contemporary social problems both at home and abroad. Among those poets who take a critical look at contemporary reality and the general problems of civilization are Vít Janota, a one-time member of the Fantasía group (Adam Borzič, Petr Řehák, Kamil Bouška), Jakub Řehák, Jan Těsnohlídek jr (the anthology Cancer [Rakovina]), Jonáš Hájek, Svatava Antošova, Petr Štengl and the books/authors from his publishing house; most recently Karel Škrabal, Marie Feryna, Jan Nemeček, Tomáš Čada, Pavel Zajíc etc. In terms of its focus and effect, this poetry seems to be superseding the earlier work of Czech songwriters and folk singers which had a broad appeal and powerful impact (Karel Kryl, Jaromír Nohavica, Jaroslav Hutka, Jiří Dědeček, Vladimír Merta and Nerez).

If we look more closely at the pigeonhole of “traditional lyric poetry”, in comparison with experimental and conceptual collections (especially post-2010) it has been on the decline and is viewed more as an anachronism, even though there are isolated examples of individuals returning to the formal methods and classical structures of poetry (most often the sonnet and the very popular haiku). However, in contemporary Czech poetry, fixed structures and classical metrical schemes are associated less with “traditional lyrical content” (Vít Slíva, Věra Rosí, Daniela Vodáčková) and more with various updated forms, or sometimes even parodies (Radek Malý, J. H. Krchovský, Ondřej Hanus, Norbert Holub, Milan Ohnisko). The question is how the term traditional lyricism is perceived and interpreted, and whether it might not actually be an illusion.

Poetry of a spiritual, metaphysical and existential nature is quite well represented (Pavel Kolmačka, Martin Josef Stöhr, J. E. Frič, Tomáš Reichel, Miloš Doležal, Adam Borzič, Petr Maděra, Pavel Petr, Věra Rosí, Marie Šťastná, Ladislav Puršl and Michal Maršálek). Spiritual poetry is mainly based on Christianity and problematizes Christian spirituality (I. M. Jirous, Roman Polách, Ondřej Hanus), or is edifying and seeks to communicate without pathos (Zdeněk Volf, Pavel Kolmačka, Zuzana Gabrišová), or is inclined towards mysticism and exaltation (Adam Borzič) or other religious teachings (Vít Kremlička, Ladislav Puršl). Writers of philosophically oriented, reflective poetry, such as Josef Hrdlička, Daniel Hradecký, Michal Maršálek and Josef Mlejnek, sometimes combine this tendency with an interest in spirituality.

Romanticizing poetry or the poetry of the new pathos is often associated with Adam Borzič, although this expressive position is shared by numerous poets from the older generation, albeit with a more inward-looking focus.

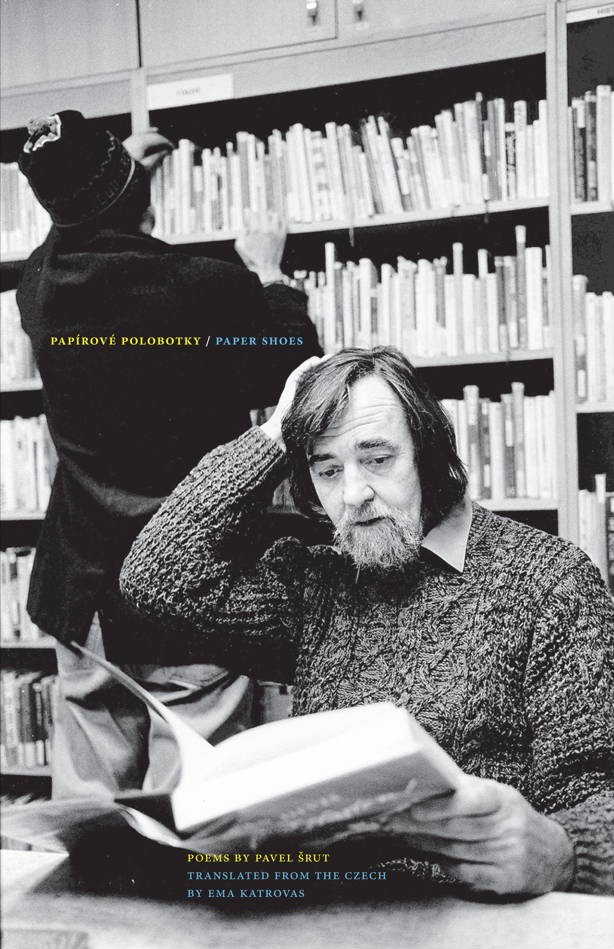

Poetry following in the Seifert–Hrubín–Skácel tradition constitutes only a small part of what is generally high-quality and well-regarded Czech literature for children: Radek Malý (winner of a Magnesia Litera) and Pavel Šrut (recipient of the State Prize for Literature), as well as the very active Jiří Žáček and Jiří Dědeček. Another aspect of this is the relatively large number of children’s songs (lyrics) by Vladimír Merta, Zdeněk Svěrák, and the music-theatre groups Kašpárek v rohlíku and Buchty a loutky. Three anthologies of Czech poetry for children edited by Petr Šrámek, summarizing the history of this industry in a “crucible” (2009, 2012), were also well received.

Pavel Šrut on the cover of the English edition of his collection ‘Paper Shoes’. Photograph: Carnegie Mellon University Press.

In our opinion, the past decade has not witnessed any major or noteworthy shift within the Czech poetry scene, with the exception of a certain exploitation of everyday empiricism, modern forms of poetic engagement with topical subjects which affect the whole of society, and a (probably temporary) rise in experimental, transitional and multimedia forms of poetry and artistic expression in general.

Certain loose groupings of authors, without a unified focus but with a more general poetic affinity, have formed around literary periodicals (Psí víno, H_aluze, and the surrealist journal Analogon) and publishing houses (esp. the circle of writers with Fra publishers, whose dramaturgical direction is provided by Petr Borkovec, and the circle of writers around the review Weles). Productive, actively publishing authors from the Czech poetry scene, classed as part of the “Prague café” and lacking a specific regional basis, continue to be influenced by the domestic classically lyrical, surrealist and experimental tradition, the Czech metamorphosis of civilism and the most distinctive figures in poetry from the past century (Holan, Skácel, Zábrana, Reynek) – but also by faith in the power and effectiveness of the unique poetic narrative, which in recent years has often been tinged with time-specific elements, especially in response to current global issues and a resurgence in religious conviction.

In a cross-section of all the styles of poetry described – even though the boundaries between them are usually blurred and they blend together in various ways in the work of individual authors or even in individual anthologies – the intention is to identify what is truly important, to search for answers to profound, existential questions, to move towards ethical values, towards truth, purity, authenticity and spiritual and aesthetic beauty – albeit interpreted in various ways. There are very few Czech poets who create lightweight, airy, or even cheerful poems. A traditional characteristic of Czech poetry would appear to be the way of working with language, placing emphasis on it or even directly reflecting on it within the poem.

For another cross-sectional look at contemporary Czech poetry, we would recommend the annual publication The Best Czech Poems (Nejlepší české básně) brought out by Host, including its forewords and afterwords, which is always compiled by two respected editors, as well as overview articles published in journals by literary critics (Jiří Trávníček, Jan Štolba, Miroslav Balaštík, Pavel Šidák, Karel Piorecký and Jakub Řehák).

Individuals in poetry

We would also like to present a brief round-up of the work of the leading figures in the contemporary poetry scene. In addition to the venerated leading lights of the older generation (Bohumila Grögerová, 1921–2014, František Listopad, 1921, Karel Šiktanc, 1928, Jiří Kuběna, 1936, Jiří Gold, 1936, Stanislav Dvorský, 1940, Petr Král, 1941, Ivan Wernisch, 1942, Miloslav Topinka, 1945, Michal Maršálek, 1949, František Dryje, 1951) and the middle generation (Vít Slíva, 1951, Svatava Antošová, 1957, Lubor Kasal, 1958, Jiří Dynka, 1959, Vít Kremlička, 1962, Pavel Kolmačka, 1962, Bohdan Chlíbec, 1963, Petr Motýl, 1964, Petr Hruška, 1964), these include “younger” poets aged between 40 and 50 (Radek Fridrich, 1968, Božena Správcová, 1969, Petr Borkovec, 1970, Vít Janota, 1970, Jaromír Typlt, 1973, Ladislav Selepko, 1973, Dan Jedlička, 1973), the strong generation of authors aged between 30 and 40 (Simona Racková, 1976, Kateřina Rudčenková, 1976, Věra Rosí, 1976, Viktor Špaček, 1976, Miroslav Černý, 1977, Radek Malý, 1977, Ladislav Zedník, 1977, Jakub Řehák, 1978, Adam Borzič, 1978, Martin Poch, 1984, Ondřej Buddeus, 1984, Jonáš Hájek, 1984), and the youngest, aged around 30, born in the late 80s (Ondřej Hanus, Marie Iljašenko, Olga Pek, Zuzana Lazarová, Jan Nemček, Alžběta Stančáková, Jonáš Zbořil, Roman Polách, Jan Delong), as well as those starting out in poetry (Matěj Lipavský, Jan Škrob, Marie Feryna), although this categorization is not without its problems.

Two living legends with similar sources of inspiration and creative outlooks, Petr Král and Stanislav Dvorský, share surrealist roots as well as an affinity with the poetic of Group 42. Their influence on contemporary poetry has mainly been through the major creative figures of the 70s generation, including Jakub Řehák and, to a lesser extent, Kamil Bouška. Of the two, Petr Král, winner of the State Prize for Literature, is more consistently active on the literary scene, regularly publishing his own original works, essays and polemics.

Two living legends with similar sources of inspiration and creative outlooks, Petr Král and Stanislav Dvorský, share surrealist roots as well as an affinity with the poetic of Group 42. Their influence on contemporary poetry has mainly been through the major creative figures of the 70s generation, including Jakub Řehák and, to a lesser extent, Kamil Bouška. Of the two, Petr Král, winner of the State Prize for Literature, is more consistently active on the literary scene, regularly publishing his own original works, essays and polemics.

In Miloslav Topinka’s relatively small but concentrated body of work there are two key themes: “the crack” and “the void”. The poet is not seeking self-affirmation in ordinary, everyday experiences; he is trying to break through these boundaries and arrive at something that lies “beyond” (Duchamp’s fourth dimension); his poetry and his essay-writing complement each other to a rare degree. Miloslav Topinka’s poetic mindset is akin to the work and personality of Arthur Rimbaud. Like him, Topinka sees the poet’s own existence as his central work. He received the Jaroslav Seifert Award for the experimental collection The Crack (Trhlina).

Karel Šiktanc is the author of an impressive and still unfinished body of work which has won him many awards. He occupies a unique position in the contemporary literary scene, as he has done since the nineties. In the early 1990s, when the structure of society was being overturned and new figures were coming to the fore from the generation of poets from the 1960s and 19670s led by Petr Hruška, Petr Borkovec and Pavel Kolmaček, Karel Šiktanc remained completely outside of this growing mainstream. In addition, the publishing policies of Host and Weles resulted in a levelling out of the poetry scene (as was described in the noughties by Petr Boháč and others), in the publication of increasingly similar collections and in the gradual reduction of the substantial poetic statement to a mere “image” (or decoration, ornament…). During this time Karel Šiktanc maintained his artistic integrity and wrote verse which makes an undeniably powerful artistic statement.

Karel Šiktanc is the author of an impressive and still unfinished body of work which has won him many awards. He occupies a unique position in the contemporary literary scene, as he has done since the nineties. In the early 1990s, when the structure of society was being overturned and new figures were coming to the fore from the generation of poets from the 1960s and 19670s led by Petr Hruška, Petr Borkovec and Pavel Kolmaček, Karel Šiktanc remained completely outside of this growing mainstream. In addition, the publishing policies of Host and Weles resulted in a levelling out of the poetry scene (as was described in the noughties by Petr Boháč and others), in the publication of increasingly similar collections and in the gradual reduction of the substantial poetic statement to a mere “image” (or decoration, ornament…). During this time Karel Šiktanc maintained his artistic integrity and wrote verse which makes an undeniably powerful artistic statement.

Jaroslav Erik Frič is one of the leading lights of the Moravian poetry scene as an active organizer of underground festivals, musician, publisher – including samizdat publishing – busker and blogger. His role as a cultural activist of the multigenre type is beyond question.

František Listopad lives permanently in Portugal. Since he began writing, he has sought to overcome the boundary between the subject and poetry. In his early work, freeing language of all pathos and striving for the essential truth of poetry was crucial to him. His later work is more existential in its focus, dealing with themes such as exile, growing old and home.

Bohumila Grögerová is a legendary poet, and not only because of her long-term collaboration with Josef Hiršal, which resulted in several major literary works. From the 1990s, one of the leitmotifs of her own poems became the ageing body (which is defied by the ageless spirit). Her poetry collection Manuscript (Rukopis), which takes the form of an intense diary narrative by a person nearing the end of their life (and yet a narrative free of any sense of resignation), was awarded the Magnesia Litera for Poetry and for Book of the Year.

Ivan Wernisch has built up an impressive body of poetry, winning awards such as the State Prize for Literature. From his dreamy beginnings, typified by the now cult anthology Winter Palace (Zimohrádek), which presented a self-contained world of magical myth, he gradually moved on to less dreamlike realms. His later work is decidedly existential, often employing elements of humour, absurdity, paradox and various neologisms, and he has also compiled three anthologies of work by forgotten poets from the history of Czech poetry. He is the recipient of numerous poetry awards.

Ivan Wernisch has built up an impressive body of poetry, winning awards such as the State Prize for Literature. From his dreamy beginnings, typified by the now cult anthology Winter Palace (Zimohrádek), which presented a self-contained world of magical myth, he gradually moved on to less dreamlike realms. His later work is decidedly existential, often employing elements of humour, absurdity, paradox and various neologisms, and he has also compiled three anthologies of work by forgotten poets from the history of Czech poetry. He is the recipient of numerous poetry awards.

Jiří H. Krchovský has been a constant presence in Czech poetry for three decades. The author’s formally strict poems (with their distinctive dactylic verse) in almost 20 collections including volumes of collected poems are unmistakeable — existential anxiety, alienation, loneliness and sexuality are some of his major themes. The poems are suffused with decadent irony, expressionist overtones, macabre and cemetery motifs as well as humourous and insightful messages. He is one of the few Czech poets whose poems have become part of popular culture (for example many of his poems are popular among secondary school students). In 1992 J. H. Krchovský received the Revolver Revue prize.

Jiří H. Krchovský has been a constant presence in Czech poetry for three decades. The author’s formally strict poems (with their distinctive dactylic verse) in almost 20 collections including volumes of collected poems are unmistakeable — existential anxiety, alienation, loneliness and sexuality are some of his major themes. The poems are suffused with decadent irony, expressionist overtones, macabre and cemetery motifs as well as humourous and insightful messages. He is one of the few Czech poets whose poems have become part of popular culture (for example many of his poems are popular among secondary school students). In 1992 J. H. Krchovský received the Revolver Revue prize.

Michal Maršálek has written a very extensive and compact body of poetry consisting of economical poems of an existential nature imbued with an Asian contemplativeness. With his ten collections of poetry, he is a core author at Dauphin publishing house.

Petr Hruška has established a whole new direction in contemporary poetry – the aforementioned “civilist” style. It is possible to come across collections which have been fruitfully inspired by Hruška, as well as others which set out to imitate him. He himself has stated that “poetry has to excite, amaze, surprise, unsettle, demolish the existing aesthetic arrangement and create a new one.” All of this without any unnecessary lyrical ornamentation. He is the recipient of several important literary awards including the State Prize for Literature and the Dresden Poetry Award.

Petr Hruška has established a whole new direction in contemporary poetry – the aforementioned “civilist” style. It is possible to come across collections which have been fruitfully inspired by Hruška, as well as others which set out to imitate him. He himself has stated that “poetry has to excite, amaze, surprise, unsettle, demolish the existing aesthetic arrangement and create a new one.” All of this without any unnecessary lyrical ornamentation. He is the recipient of several important literary awards including the State Prize for Literature and the Dresden Poetry Award.

Petr Borkovec made his mark as a distinctive figure in poetry in the early 1990s when he won the Jiří Orten Award for his second collection. In his early collections he created lyric poems which were inspired by Reynek. His older works show the influence of the foreign poets he has translated (he has received a number of prestigious literary prizes for his translations). This artistic period was characterized by a gradual move away from classical figures in poetry and a focus on describing and recording. Today it is possible to talk about a “Borkovec style” in Czech poetry, which can be seen in the poetics of several poets from the 1970s and 1980s (e.g. Bouška, Řehák, Hájek, Lipavský).

Petr Borkovec made his mark as a distinctive figure in poetry in the early 1990s when he won the Jiří Orten Award for his second collection. In his early collections he created lyric poems which were inspired by Reynek. His older works show the influence of the foreign poets he has translated (he has received a number of prestigious literary prizes for his translations). This artistic period was characterized by a gradual move away from classical figures in poetry and a focus on describing and recording. Today it is possible to talk about a “Borkovec style” in Czech poetry, which can be seen in the poetics of several poets from the 1970s and 1980s (e.g. Bouška, Řehák, Hájek, Lipavský).

Pavel Kolmačka is undoubtedly one of the most distinctive poets of his generation. From the first collections, which show the rural influence of Reynek’s work, his poetics have gradually become more civilist. In his exceptional collection The Sea (Moře), he intensively captures the moment of becoming a parent, and in Kolmačka’s latest powerful poetry collection, Wittgenstein is Beating a Pupil (Wittgenstein bije žáka), there is a socio-critical and ironic undertone to his poetry.

Pavel Kolmačka is undoubtedly one of the most distinctive poets of his generation. From the first collections, which show the rural influence of Reynek’s work, his poetics have gradually become more civilist. In his exceptional collection The Sea (Moře), he intensively captures the moment of becoming a parent, and in Kolmačka’s latest powerful poetry collection, Wittgenstein is Beating a Pupil (Wittgenstein bije žáka), there is a socio-critical and ironic undertone to his poetry.

Characteristic features of Petr Halmay’s poetry are pragmatism and descriptiveness. However, in contrast to this apparently impersonal approach, his early work reveals the existential anxiety of the lyric subject stemming from the experience of finding oneself alone in a world of deception. In Halmay’s more mature work, his poetics open up to more general themes, for example, the conflict in the former Yugoslavia (Being [Bytost]). In the collection Tail Lights (Koncová světla), there is an inclination towards epic poetry, with micro-stories often being inserted into the texts. In his latest book of poems, Ice Crawler (Ledolam), the poet’s language is working towards its purest, most constrained form of expression; the poems are characterized by scepticism towards the ephemeral phenomena of the contemporary world.

Štěpán Nosek became known for two collections of distinctive, strongly delineated poetry. He avoids any kind of ornamentation in his work. In his books Negative (Negativ) and At Liberty (Na svobodě), he records everyday situations and observations with an almost photographic precision. There is nothing in Nosek’s poetry which is there just for effect; the tension which is painfully present within it comes from hints and often from the spaces between and after the verses, rather than from the verses themselves.

Petr Motýl is a supremely lyrical poet. Since the beginning (the mid-1990s), he has been strongly influenced by the work of Ivan Wernisch, while later he drifted between factuality (the collection Crazy Fridrich (Šílený Fridrich) and more dreamlike lyricism. In his work, the legacy of Ivan Blatný and Group 42 is combined with traditional Czech lyricism (in the spirit of Seifert).

Vít Slíva, unofficial Brno poetry guru; while working as a secondary-school teacher, he “raised” several important poets from the 1990s who were grouped around the journal Weles. He himself owes a debt to the poetic of Vladimír Holan, though his own personal contribution and temperament helped him to go beyond this and create coherent and original work with a profound feeling for the stylistic quality of the verse. Like all distinctive poets, Slíva also exerted a strong gravitational pull, though the poets who were enchanted by Holan’s legacy as mediated by Vít Slíva did not achieve his greatness and their work from the 1990s is characterized by the construction of poems according to a scheme: observing the backdrop of the world, reflection, a general or spiritual message. Vít Slíva was awarded a Magnesia Litera for Poetry.

Milan Ohnisko’s work combines honesty, playfulness, absurdity and irony, lightness as well as gravity. He frequently uses a play on words as a prelude to making a perfectly rational point. A collection of his poetry was published in 2012 under the title Och!

Ladislav Selepko is a poet who has been writing, though not publishing, for several decades. His work is influenced by surrealism and consists of a remarkable number of self-contained cycles and collections. It is unusual for such a distinctive poet to make his debut at a relatively advanced age, as he did with the collection Nineteen Cities (Devatenáct měst), which is basically an anthology of all his previously unpublished work.

Milan Děžinský’s poetry typically emphasizes the poetic image. Whether on an intimate level or one of nature lyricism, it acts as a basis for philosophical reflection and meditation. As a distinctive representative of the middle generation of poets, he has been nominated three times for the Magnesia Litera for Poetry, and he was the first Czech author to be awarded the international Václav Burian Prize.

Božena Správcová has written three collections of poetry and several poetic songs. In her work she often employs the principles of a game; her texts create an entire world with its own metaphysical, poetic myth. In this respect the collection Strašnice is particularly outstanding, with the poet’s artistic principles coming together to create a rich, varied and profoundly human mystical space.

Svatava Antošová’s early poetry was strongly influenced by beat and rock poetry. There are verses filled with explicit carnality, pataphysics and a hallucinogenic atmosphere. A similar openness – including in sexual matters – can also be found in the author’s later work. The poet has an exceptional talent for bound verse and for presenting her poetry, which she puts across to audiences very effectively, including her performance pieces.

Svatava Antošová’s early poetry was strongly influenced by beat and rock poetry. There are verses filled with explicit carnality, pataphysics and a hallucinogenic atmosphere. A similar openness – including in sexual matters – can also be found in the author’s later work. The poet has an exceptional talent for bound verse and for presenting her poetry, which she puts across to audiences very effectively, including her performance pieces.

Alongside Josef Hrdlička, Daniel Hradecký is one of the few contemporary poets who uses meditative philosophical reflection in his work. Critics typically compare his work to that of Ivan Diviš and Vladimír Holan, and he distils the essential from both of them – Holan’s submersion in philosophy and Diviš’s wide-ranging energy.

Jaromír Typlt immediately came to the attention of critics and readers with a distinctive book that encapsulated his first three published collections, Lost Hell (Ztracené peklo, 1994). His early collections emphasize imagination, freedom, association and going beyond the boundaries of text towards sound and image. Typlt’s later work increasingly began to focus on ways of extending the spoken word into other media, thereby giving rise to collections of unique sound recordings, stage performances, short films and improvisation. This propensity towards using various channels to convey poetry is still present in Typlt’s work.

Jaromír Typlt immediately came to the attention of critics and readers with a distinctive book that encapsulated his first three published collections, Lost Hell (Ztracené peklo, 1994). His early collections emphasize imagination, freedom, association and going beyond the boundaries of text towards sound and image. Typlt’s later work increasingly began to focus on ways of extending the spoken word into other media, thereby giving rise to collections of unique sound recordings, stage performances, short films and improvisation. This propensity towards using various channels to convey poetry is still present in Typlt’s work.

Kateřina Bolechová is a writer of economical, civilist-oriented – and yet raw – poetry, mostly written with uncompromising irony and candour. Her collection The Ceiling Above Me Will One Day Disappear (Strop nade mnou jednou zmizí, 2016) showed that she was also a writer of long compositions and poetry in prose, which was sensitively accompanied by her own collages.

In his earlier collections, Martin Reiner set up a contrast between a Parnassian, classicist form of verse and communication that was rooted in the present and often bitterly ironic. In his most important collection Décimas (Decimy), there is a stronger tendency towards humour and playfulness. His later works are marked by a more civilist tone and a certain reconciliation.

In his earlier collections, Martin Reiner set up a contrast between a Parnassian, classicist form of verse and communication that was rooted in the present and often bitterly ironic. In his most important collection Décimas (Decimy), there is a stronger tendency towards humour and playfulness. His later works are marked by a more civilist tone and a certain reconciliation.

At the beginning of the 1990s, Martin Stöhr, together with Pavel Petr, was characterized as a spiritual poet. Typical of Stöhr’s verse from this period is the restrained language and the use of rhyme. Lyrical motifs from nature are often combined with Christian ones. Later, in the collection Temporary Residence (Přechodná bydliště, 2004), the author’s relationship with God becomes more problematic. The rhymes begin to disappear and more attention is paid to the transience and rootlessness of events in the world. Stöhr’s latest poetic creation, Laughter from a Dream (Smích ze sna) is freer in style than the previous ones and contains frequent allusions to the work of other writers.

Jiří Dynka attracted attention with his experimental work in the mid-1990s. His early poems typically made use of the typography of the verse: frequent changes in font as well as lettering size, strings of adjectives etc. Despite the demands it places on the reader, this is lyric poetry with a strong focus on human existence. He gradually moved away from experimentation to more traditional forms of verse, but the lyrical focus remained. Thematically, Dynka has increasingly turned to carnality, both in terms of pleasure and the opposite – pain and sickness. In his most recent collections, again essentially lyrical, we find ourselves in the chronotopes of Prague’s cemeteries, parks and cafés.

Jiří Dynka attracted attention with his experimental work in the mid-1990s. His early poems typically made use of the typography of the verse: frequent changes in font as well as lettering size, strings of adjectives etc. Despite the demands it places on the reader, this is lyric poetry with a strong focus on human existence. He gradually moved away from experimentation to more traditional forms of verse, but the lyrical focus remained. Thematically, Dynka has increasingly turned to carnality, both in terms of pleasure and the opposite – pain and sickness. In his most recent collections, again essentially lyrical, we find ourselves in the chronotopes of Prague’s cemeteries, parks and cafés.

Vít Janota has written seven extremely compact poetry collections, for which he was nominated for the State Prize for Literature. In all of them he managed to skilfully combine “engagement” in the contemporary world with metaphysics and existentialism. His body of work also contains a long poem published as a book and a new anthology of conceptual poems based upon the names of Prague streets.

Dan Jedlička is concerned with the everyday in all its guises. This theme is viewed with irony and humour, but also with a lightness of touch – somewhere in the background are the constantly recurring motifs of alienation, absurdity and other existential matters.

Radek Fridrich, recipient of a Magnesia Litera for Poetry, has written seven collections of poems inspired by the landscape of North Bohemia, in particular the area of the former Sudetenland. The fate of the Sudeten Germans, the landscape of his home town of Děčín and the intermingling of languages provide material for an exorcism and for the creation of local myths and poetic stories about people both real and imagined.

Radek Fridrich, recipient of a Magnesia Litera for Poetry, has written seven collections of poems inspired by the landscape of North Bohemia, in particular the area of the former Sudetenland. The fate of the Sudeten Germans, the landscape of his home town of Děčín and the intermingling of languages provide material for an exorcism and for the creation of local myths and poetic stories about people both real and imagined.

In the 1990s, Vít Kremlička had already positioned himself outside of the mainstream, going against the conventional poetics of the time. He was one of the few who confronted the burning issues of the day; for example, the war in Bosnia. However, he is not a mere agitator – first and foremost, he is a poet endowed with an unquestionable gift for musicality and inventiveness, as he has proved in his work, which includes experimental sonnets and “detective poems”. He has been awarded a number of literary prizes for his poetry, including the Jiří Orten Award and the Revolver Revue Award.

Radek Malý, recipient of several Magnesia Litera prizes, is an excellent stylistic poet and translator, as well as a highly regarded author of children’s poetry.

Radek Malý, recipient of several Magnesia Litera prizes, is an excellent stylistic poet and translator, as well as a highly regarded author of children’s poetry.

Jakub Řehák is without a doubt one of the most significant poets of the generation born in the 1970s. After his promising debut work, The Lights Between the Boards (Světla mezi prkny, 2008), came A Trap for Brigita (Past na Brigitu), which evoked an unusually positive response and secured a Magnesia Litera for Poetry. Řehák has managed to combine the poetics of authors following in the tradition of Vratislav Effenberger and Group 42 with contemporary trends – e.g. emphasizing the character of the writer’s artistic statement in the manner of the Fantasía group (paradoxically, Řehák was the most successful in realizing this group’s manifesto). Řehák recently brought out his third collection.

Jakub Řehák is without a doubt one of the most significant poets of the generation born in the 1970s. After his promising debut work, The Lights Between the Boards (Světla mezi prkny, 2008), came A Trap for Brigita (Past na Brigitu), which evoked an unusually positive response and secured a Magnesia Litera for Poetry. Řehák has managed to combine the poetics of authors following in the tradition of Vratislav Effenberger and Group 42 with contemporary trends – e.g. emphasizing the character of the writer’s artistic statement in the manner of the Fantasía group (paradoxically, Řehák was the most successful in realizing this group’s manifesto). Řehák recently brought out his third collection.

The poetry of Adam Borzič is characterized by the emotive, impassioned intensity with which it is put across. Nor does it eschew the “new pathos” (which is in complete accordance with the manifesto of the Fantasía group, of which Borzič, along with Bouška and Petr Řehák, was a founding member). In his work, Borzič takes a sensitive view of the wider problems of the contemporary world, which he sets within a more general mythical framework, linking them to diverse spiritual and philosophical reflections and insights.

The cornerstone of Kamil Bouška’s poetry is his emphasis on image and expression. Civilist-oriented, generally applicable texts alternate with raw and harrowing narratives.

The poems of Viktor Špaček abandon established lyrical approaches and are closer to the work of Petr Hruška in terms of their civilist poetic. In contrast to Hruška, however, Špaček is more “insolent” and vitriolic in describing the problems of the contemporary world – interpersonal relationships, alienation, isolation, ageing, etc. His work marries a talent for observation with a sense of irony.

Marie Šťastná’s work ranges from a certain lyrical spontaneity to a completely purified form of expression. She received the Dresden Poetry Award in 2010.

Kateřina Rudčenková attracted attention with her very first collection, Ludwig, which was inspired by Thomas Bernhard’s novel. From this strong, successfully stylized debut, the poet gradually moved towards more civilist-oriented and intimate areas, and it is in this vein that she wrote her best poetry collection to date, Walking on Dunes (Chůze po dunách), for which she was awarded the Magnesia Litera for Poetry.

Kateřina Rudčenková attracted attention with her very first collection, Ludwig, which was inspired by Thomas Bernhard’s novel. From this strong, successfully stylized debut, the poet gradually moved towards more civilist-oriented and intimate areas, and it is in this vein that she wrote her best poetry collection to date, Walking on Dunes (Chůze po dunách), for which she was awarded the Magnesia Litera for Poetry.

Simona Racková is the author of emotional, personal and, at the same time, civilist narratives. Through them, Racková, like Sylvia Plath, delivers a strong message about the status of the female lyric subject in this world, which she confronts in various roles. She won the Dresden Poetry Award for her poems in 2016.

Jitka Srbová has written three collections of poetry so far. Together with Vít Janota, she is one of the core authors at the Dauphin publishing house. She has a fine sense for the expressive potential of situations and a well-honed sense of humour and is a wonderful observer of people and the situations they find themselves in. Her most recent poetry collection, The Forest (Les), in particular attracted a great deal of attention.

Josef Straka is one of the most well-established poets from the middle generation and plays an active part in organizing the literary scene. In his raw, existential texts, he describes the position of the poetic subject in today’s world. His verses are borne upon a wave of spontaneity and tend towards a deliberate quality of monotonal litany; the power of conscious narrative is placed before the creative use of language.

Tomáš Reichel’s two published collections showed him to be a spiritually oriented author. One of his basic motifs is a journey of initiation during which the lyric subject confronts his own internal contradictions (for example, spirituality versus physicality). The decadent tradition provided the starting point for his stylistically polished verse. However, Reichel later moved away from writing poetry.

One of the leading poets in the circle around the Weles journal is Vojtěch Kučera, whose poems are characterized by their unpretentiousness and a certain degree of minimalism. These are short records, fragments of conversations and everyday situations. Taken as a whole, Kučera’s texts form a kind of poetic diary. One remarkable experiment is the collection of texts entitled Stillness (Nehybnost), in which the author links together virtual and printed media in an original way.

Ladislav Puršl is the author of three poetry collections, but it was the second, entitled Map of the Newts (Mločí mapa), which really brought him to attention. In it we find an urgent lyricism replete with motifs of death, the landscape and spirituality.

Robert Fajkus is part of the circle of poets grouped around Vít Slíva and the journal Weles. His lyrical poems offer a personification of the landscape with spiritual overtones, but also with a romantic lyricism. With a light and easy touch – albeit often in hints – he expresses the fundamental questions of human existence.

Petr Maděra’s poetic is akin to the nature lyricism of the poets grouped around Weles. He has written three collections of poetry so far, the first two being clearly influenced by the poetic of Vladimír Holan. A more civilist tone permeates his third collection – Filtration Papers (Filtrační papíry).

Bogdan Trojak was most active in publishing poetry in the mid-1990s and in the first decade of the 21st century. He has now gone back to writing for children. His work is typified by his sophisticated and inventive use of language and his ability to build a viable poetic myth imbued with a magical atmosphere (e.g. the collection Uncle Kaich Is Getting Married [Strýc Kaich se žení]).

Bogdan Trojak was most active in publishing poetry in the mid-1990s and in the first decade of the 21st century. He has now gone back to writing for children. His work is typified by his sophisticated and inventive use of language and his ability to build a viable poetic myth imbued with a magical atmosphere (e.g. the collection Uncle Kaich Is Getting Married [Strýc Kaich se žení]).

Jan Těsnohlídek jr’s surprising debut work brought a generational narrative by a teenage poet to the Czech literary setting and secured him the Jiří Orten Award. His next collection, Cancer (Rakovina), continued in a similar vein, although it had lost that suprapersonal bloom. He recently published a third collection of poetry, The Main Thing Is To Save Yourself (Hlavně zachraň sebe), in which he manages to successfully present his own feelings about life as generational ones.

Kateřina Kováčová received the Jiří Orten Award for her debut work, Nests (Hnízda), in which she builds on lyrical nature motifs which serve as a background to the powerful narrative of the lyric subject. In her next book, I Sensed a Forest (Sem cejtila les), the subjectivity is artfully dissolved into a game with language; together the poetry collections form a coherent mythical space.

Irena Šťastná has written three collections in which the lyrical earthiness of rural chronotopes mingles with the raw narrative of the lyric subject.

Věra Rosí won the Jiří Orten Award for her debut work. In subsequent collections she once again demonstrated her refined sense for regular form and rhythm, as well as for the symbolism of the landscape and the movement within it as a way of illustrating states of being and thought.

Jonáš Hájek has written three poetry collections to date. His debut work, Debris (Suť), for which the author received the Jiří Orten Award, clearly brings together the influence of a number of poets – mainly Petr Hruška, Vít Slíva, Petr Borkovec and the German expressionists. It had a mixed reception. Nevertheless, it was evident that a poet had entered the scene who thinks very seriously about poetry, has absorbed poetic traditions and consciously attempts to follow on from them. Hájek’s second collection, National History (Vlastivěda), was more descriptive. His third book of poetry, Poems 3 (Básně 3), presents stylistically sophisticated texts and is open to the world and current issues.

Marie Iljašenko demonstrated her unquestionable talent through her debut work, Osip Is Heading South (Osip míří na jih, Host 2015). Her poetry combines the influence of Joseph Brodsky with other sources of inspiration that have not yet been explored in the Czech context, thus bringing a fresh new European voice to contemporary poetry.

Martin Poch is one of the most distinctive poets from the 1980s generation. With complete assurance, his poetry brings together opposites: high and low, absurdity and seriousness, unrestrained physicality and coldness. It is a poetic full of contradictions – and that is where its potential stems from. One remarkable aspect of Poch’s poetic is the process that takes place within the language: his best work can be described as a poetic event in the sense that Petr Král spoke about (e.g. in The Best Czech Poems of 2011).

One of the most distinctive talents from the younger generation is Ondřej Hanus. In his work he moves from stylistically refined verse that successfully brings the poetic tradition up to date, to a freer and more civilist narrative which still continues to place great emphasis on the precise use of poetic figures. His work combines a distinctive, individual vision with stylistic virtuosity, the earthly with the spiritual. He received the Jiří Orten Award for his collection Scenes (Výjevy).

Ondřej Buddeus is a versatile writer who aims primarily for originality and purity. He has absorbed modern global trends into his work. He typically works with a concept and a premeditated plan; he combines economy of language with a sophisticated game that he plays with the reader. He is the recipient of both a Magnesia Litera and the Jiří Orten Award.

Tomáš Gabriel’s debut work contains a civilist poetic replete with irony, questioning the essence of the phenomenal world. In his second collection, Gabriel energetically embarked on a deconstruction of ingrained approaches to poetry, sometimes verging on parody and farce. He does not shy away from aphorisms or linguistic barbs. With a touch of hyperbole, it could be said that some of the more free-flowing passages pose a trap for the reader.

Roman Polách is a promising young poet whose debut work transformed everyday phenomena and traces of memory with a spiritual/reflective tone into a kind of silent incantation.

Pavel Bušta made his poetry debut with Doublets (Dvojtváří). Two different attitudes merge with each other within the book: a “serious” one, whereby the poet’s subject has a distinctive cultural and historical resonance, and an ironic one, which casts doubt on the nature of modern worldly vices.

Jonáš Zbořil is the author of the powerful poetry debut Podolí. The book contains rich imagery, veined with the sensitivity of the poet’s subject, as it takes us on a walk through the city streets and the paths of memory and the internal landscape.

Zuzana Lazarová is the author of the slim, mature debut work The Iron Shirt (Železná košile). Hers is a hard, unapologetic style of verse, artfully employing linguistic structures and also fruitfully inspired by surrealist approaches.

Olga Stehlíková & Ladislav Zedník

General characteristics of contemporary Czech poetry by Olga Stehlíková

Individuals, passage about literary websites in the introductory synthesis by Ladislav Zedník

Our thanks go to Ondřej Hanus for his comments.

Translated by Graeme Dibble