If there is something Czech literature can be proud of, it is the quality of its books for children and young adults, which combine excellent artwork and literature. This month’s feature presents some of the best titles published at the end of 2014 and through 2015 — from fairy tales to art history, murder mysteries to avant-garde language games. For more Czech books for children and young adults we recommend having a read through the Golden Ribbon Award winners and the books selected for the Best Children’s Books project. We hope you enjoy our selection. As everyone knows, the best books for children are also great literature for adults!

Contents

Olga Černá: This is Prague

Miloš Kratochvíl: Prisoners of the Silver Sun

Lenka Brodecká: The Search for a Star

Jana Šrámková: Susie in the Gardens

Ondřej Horák: Why Paintings Don’t Need Names

Daniela Fischerová: Deformatory

Daniela Krolupperová: A Crime in Prague’s Old Town

Ivan Wernisch: Plop! The Lebott’s Korc Unscrooed, He Upguzzeled Liqueur

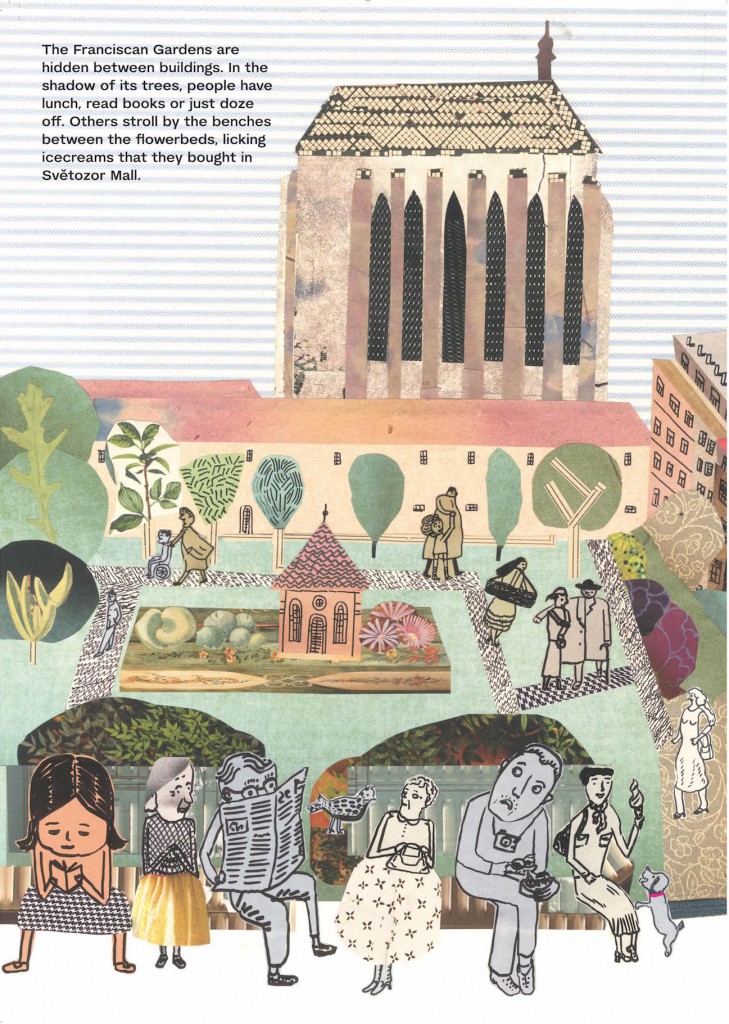

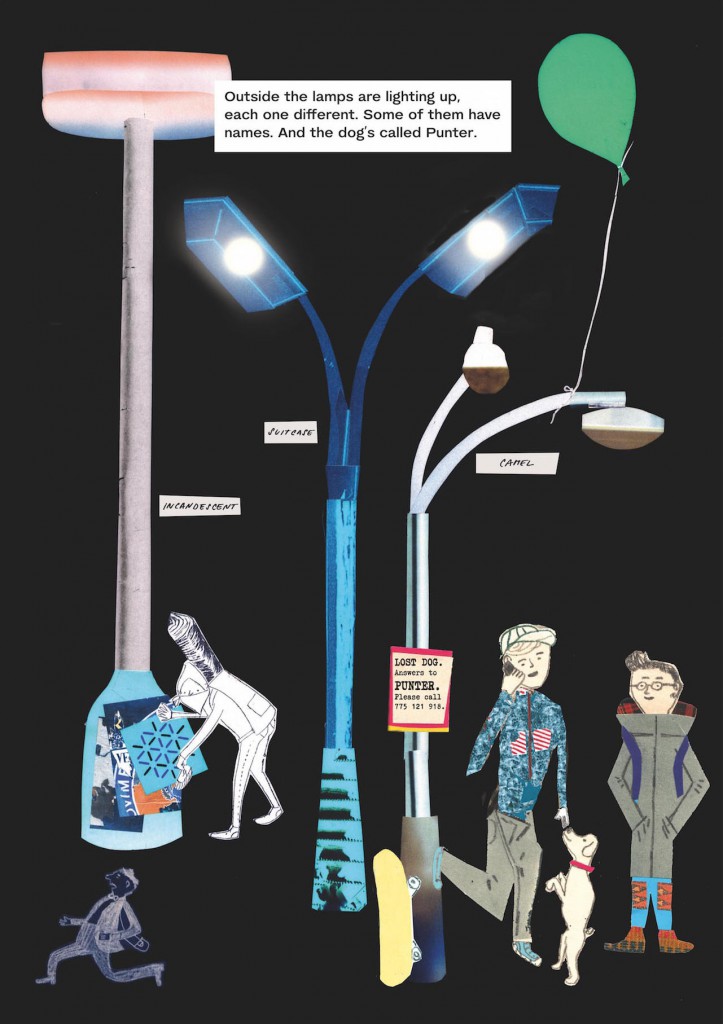

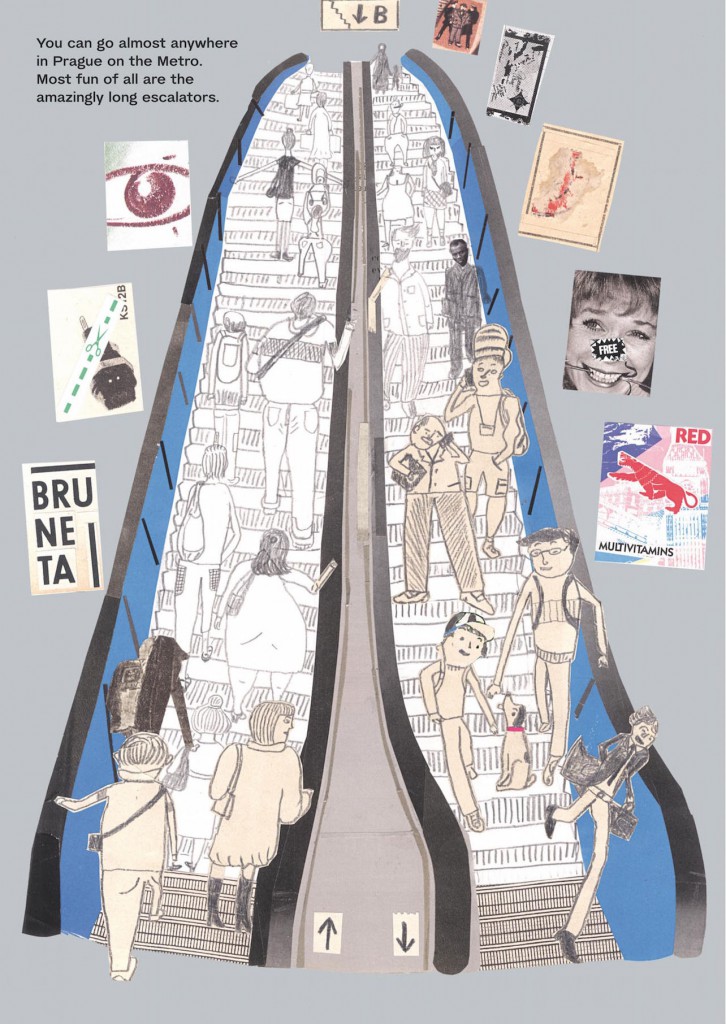

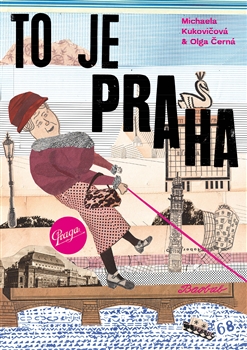

Olga Černá & Michaela Kukovičová

This is Prague

To je Praha

(Baobab, 60 pages)

Age: 5+

Although exile-based author of picture books for children, Miroslav Šašek (1916–1980), was a native of the city of Prague, he was not recognised in his homeland until the 21st century. Having published his essential collection of guides to the world’s nineteen big cities, which in their time entertained youngest readers on all continents, Šašek’s grandniece Olga Černá – co-founder of the foundation bearing the artist’s name – decided to author the never-written tribute to Prague, employing Šašek’s typical condensed style. Accompanied by a stray dog and a couple of skateboarding kids, she examines the magic of the Mother of All Cities in a way that is sure to please all structuralists: dealing with it one topic at a time. Michaela Kukovičová, whose collage-like view of reality is interspersed with naivist drawings, provides the city’s star-clad fame with a more civil outline. After all, it does boast the world’s largest castle in regular use, it used to host Stalin’s most appalling monument, Kafka’s beetle by the name of Gregor Samsa crawled along its streets, Golem strode in its alleyways and a special type of sandwich, “chlebíček”, was born here a hundred years ago. The publisher, Baobab, has also released an English edition of the book translated by Justin Quinn.

Praise

“With her original artistic style, Michaela Kukovičová has perfectly captured the atmosphere of various places in Prague and Olga Černá, Šašek’s grandniece, has created texts tailored for children which adults will also enjoy reading.”

— Johana Labanczová, iLiteratura

Links

Publisher: www.baobab-books.net

Excerpt from the English edition

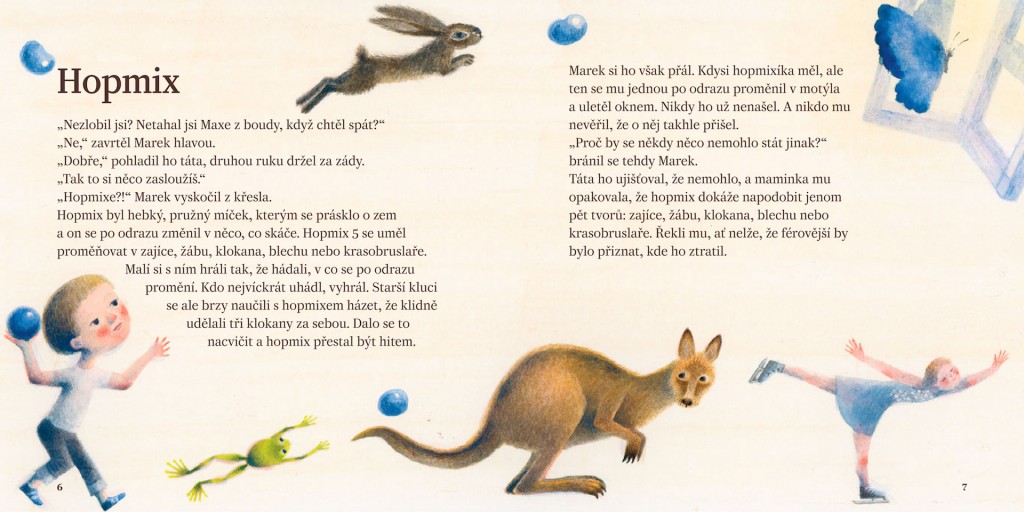

Miloš Kratochvíl & Iku Dekune

Prisoners of the Silver Sun

Zajatci stříbrného slunce

(Triton, 98 pages)

Age: 6+

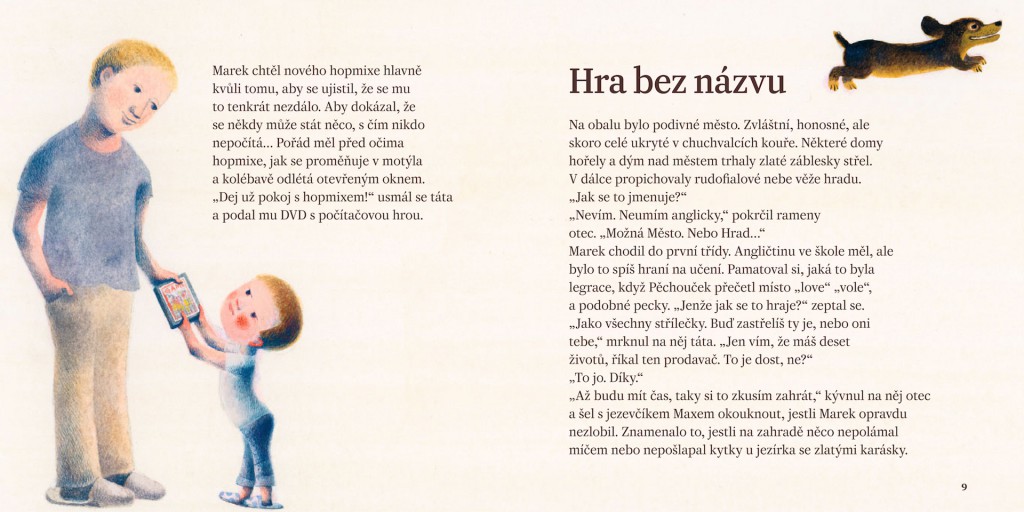

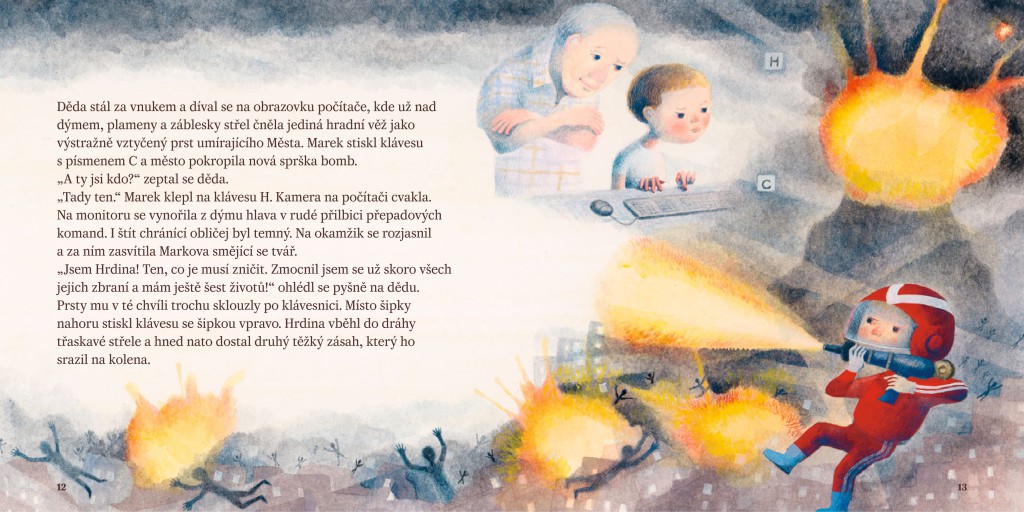

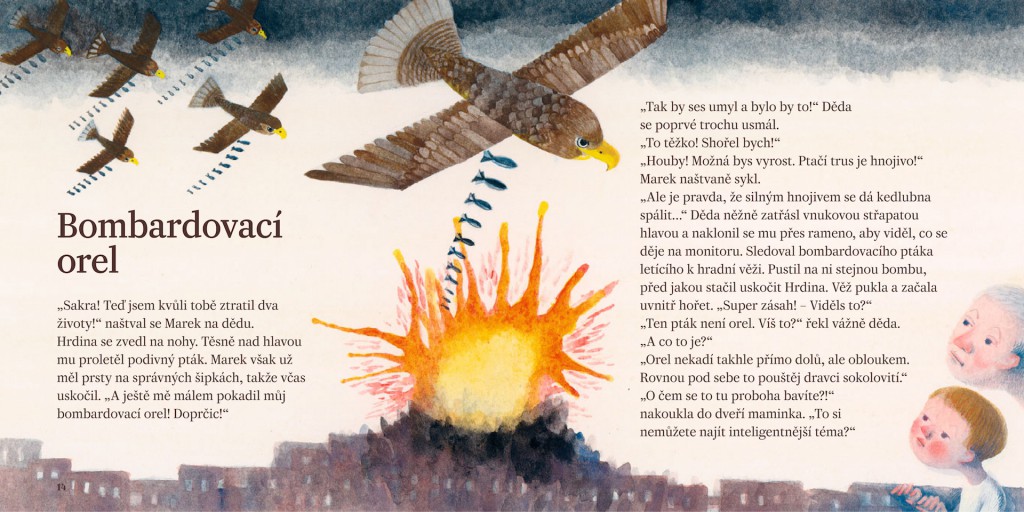

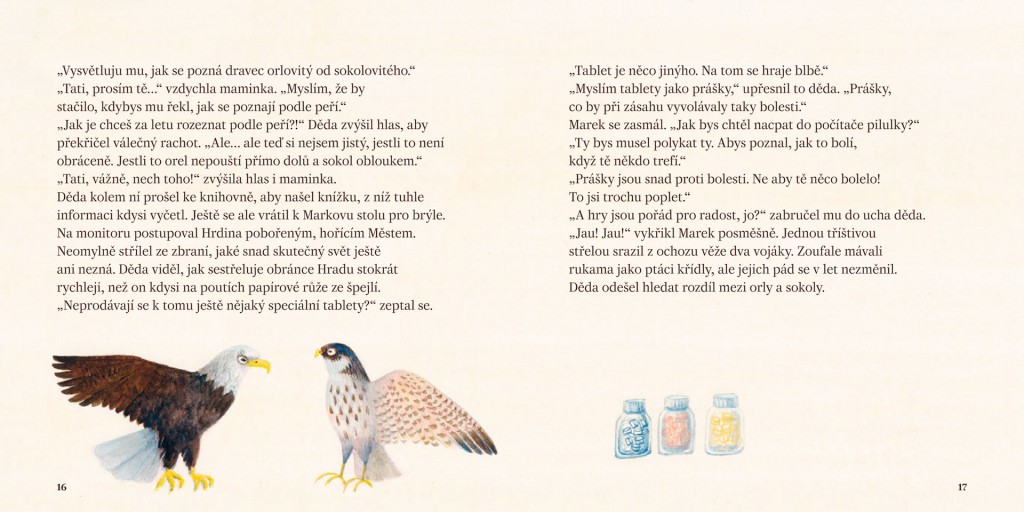

In this prose the seasoned author delivers a surprising message and lets us wonder what genre for young readers he has created this time. The dystopian variation conjures up a world in which computer-game backdrops materialise into reality. A six-year-old boy named Mark, who lives in the near future, gets a DVD from his father with a game called The City, and becomes addicted to it. Eventually he manages to destroy the City and still have one or two lives left, despite his family’s frequent reproaches that games should not be played for the joy of killing. In a dream, Mark suddenly finds himself within the City’s ruins, guided by a little boy whom he had wounded with three shots. Mark, who is responsible for all the destruction, now ponders the City’s ruins and the disk of the silver sun, which rises above the rebuilt metropolis, and children and adults alike are faced with a disquieting question concerning the limits of the virtual world. Iku Dekune’s charming illustrations stand out as faithful representations of a child’s imagination.

Praise

“Miloš Kratochvíl’s book is unique both because of its text and its illustrations by Japanese artist Iku Dekune… I’d be surprised if this exceptional book didn’t win the children’s book of the year award.”

— Mik Herman, čítárny.cz

Links

Publisher: www.tridistri.cz

Illustrations

-

Excerpt ▼

Hopmix

“You weren’t naughty, were you? You didn’t drag Max out of his kennel when he wanted to sleep?”

“No,” said Mark, shaking his head.

“Good,” said Dad, patting him on the head, his other hand held behind his back.

“In that case you deserve a reward.”

“Hopmix?!” Mark leapt up from the armchair.

Hopmix was a smooth, elastic ball that you slammed onto the ground, and as it bounced up it turned into something that jumps. Hopmix 5 could transform into a hare, a frog, a kangaroo, a flea or a figure skater. Little children played with it by guessing what it would change into on the rebound. The person who got it right most times was the winner. But older boys soon learned how to throw the hopmix so that they could get three kangaroos in a row. You could learn the trick and hopmix stopped being a hit.

But Mark wanted one anyway. He used to have a hopmix, but one day that one had bounced up and changed into a butterfly and flown away through the window. He never found it again. And nobody believed that that was how he had lost it.

“Why couldn’t something different happen for a change?” Mark had protested.

Dad assured him that it couldn’t, and Mum repeated to him that hopmix was only able to take the form of five creatures: a hare, a frog, a kangaroo, a flea or a figure skater. They told him not to lie, that it would be better to confess where he had lost it.

Mark wanted a new hopmix mainly so that he could make sure he hadn’t dreamt the whole thing up. So that he could prove that sometimes something totally unexpected can happen… In his mind’s eye he kept seeing the hopmix changing into a butterfly and fluttering out through the open window.

“Enough about hopmix!” laughed Dad, handing him a DVD of a computer game.

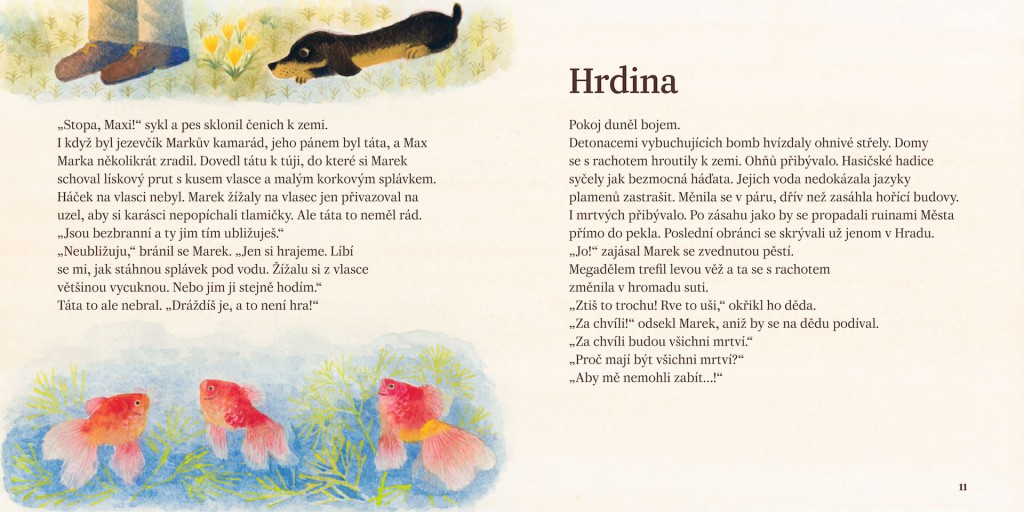

The Game without a Name

On the cover was a strange town. Odd, splendid, but almost entirely hidden beneath clouds of smoke. Some of the buildings were on fire, and golden flashes of gunfire tore through the smoke above the town. In the distance the turrets of a castle pierced the red and purple sky.

“What’s it called?”

“I don’t know. I don’t speak English,” his father shrugged. “Maybe The City. Or The Castle…”

Mark was in the first year of school. He did English, but it was more like playing at learning. He remembered how funny it was when Pěchouček read “vole” instead of “love”, and similar gems. “But how do you play it?” he asked.

“Like all shoot-em-ups. Either you shoot them or they shoot you,” said Dad, winking at him. “I only know that you have ten lives – that’s what the shop assistant said. That should be enough, right?”

“Sure. Thanks.”

“When I have time, I’ll have a go at it myself.” His father nodded at him and off he went with Max the dachshund to check that Mark really had behaved himself. That meant that he hadn’t damaged anything in the garden with his ball or trampled on the flowers by the pond with the goldfish in it.

“Max, track!” he hissed and the dog lowered his muzzle to the ground.

Even though the dachshund was Mark’s friend, it was his father who was his master, and Max had betrayed Mark several times. He led Dad to the thuja tree in which Mark had hidden his hazel rod with a piece of fishing line and a small cork float. There was no hook on the line. Mark just tied worms onto the line with a knot so that the goldfish wouldn’t pierce their mouths. But Dad wasn’t happy about it.

“They’re defenceless and when you do that you’re hurting them.”

“I’m not hurting them,” protested Mark. “We’re just playing. I like how they pull the float under the water. They usually suck the worm from the line. Or I throw it to them anyway.” But Dad disagreed. “You’re teasing them, and that isn’t a game!”

(Translated by Graeme Dibble)

Lenka Brodecká & Tereza Ščerbová

The Search for a Star

Hledá se hvězda

(Host, 232 pages)

Age: 7+

An exceptional fairy tale by today’s standards, featuring an original parable of the struggle between good and evil. A princess and her lone royal father find hope in a bright star appearing over their kingdom on the day of the queen’s demise. One day the star vanishes and its loss adopts a deeper significance, as it had the ability to turn evil beings into stones, which were then hurled into the Devil’s Canyon. Immediately, darkness reclaims the land and the malice of some of the castle’s inhabitants is thriving. Their evil intentions are revealed by two non-adult heroes: the princess and a newly appointed little jester. Younger school children will find the story’s various twists breathtaking, including the final thrilling showdown in the form of a battle for the kingdom’s deliverance. Their experience will be underpinned by Tereza Ščerbová’s illustrations, whose pen-drawings skilfully blend with page-wide illustrations, gently complementing the book’s melancholic feel.

Trailer

Praise

“This adventure detective story is full of surprises. It slowly draws the reader in deeper and deeper. In the end nothing is certain and the adult characters, which surround the little Princess, show how much love and desire can affect people.”

— Jana Zítková, iLiteratura

Links

Publisher: nakladatelstvi.hostbrno.cz

Illustrations

-

Excerpt ▼

The Day Before

At dawn he crossed over the border into the kingdom of the Shining Stars. He was travelling alone and on foot. It is difficult to say whether he was a boy or a man, but those who came across him on his journey claimed that he was a jester, because he was wearing a red outfit with a jagged hem, a horned hat, and long narrow boots with curled toes. He was carrying a red knapsack on his back.

In the afternoon he stopped and sat down on a small tussock, laid out a cloth napkin on his lap and ate a modest lunch. He seemed to be deep in thought. Then he pulled out a large notebook from his knapsack and wrote something down. He looked up at the sky and soon continued on his way. Tomorrow he would be kneeling before the local king.

The Princess

The princess awoke in the morning, stretched and put on her pink slippers. What a day it’s going to be today! she thought excitedly. And she ran straight to the window. She looked out at the zigzagging path which led to the outer gate of the castle, but so far nothing, no-one in sight. So, time to wash, get dressed and brush her hair. The door to the bathroom banged shut.

The princess’s name was Princess. Honestly. Her mother had given her the name. She had also given her her looks – a round face, golden hair and a mischievous glint in her eye. All of those who remembered the queen were astonished by the likeness, but Princess didn’t remember her mother. She knew what she looked like from pictures, and they had also told her that her mother was very kind and courageous, but Princess had no idea that she had the same laugh as her, that they both liked to gaze into the distance and dream, and that if something strange should suddenly happen, she would cover her mouth with both her hands, just like her mother. No-one told Princess this – even though her father was still around and perhaps also someone else who loved these similarities.

Princess gave herself a cursory wash, got dressed in the twinkling of an eye and was soon back at the window surveying the winding path. At the same time her nimble fingers braided a plait which fell over her shoulder – it was already half a metre long and the same amount of hair remained. The path to the castle was still empty. Princess didn’t like it – the sun was already high above the trees and was beginning to heat up, so where was everyone? A pair of white doves flew around the window. Princess sighed and carried on with her braiding.

Just when it seemed to her that a traveller had appeared on the road far off in the distance, someone knocked on the door to her pink chamber. It was the master of ceremonies in his festive beret. He poked his head inside and wished Princess a good morning.

Princess turned towards him eagerly. “Well, are they here yet? How many of them are there?”

“No-one has arrived yet, Your Highness,” replied the master of ceremonies. “But no doubt they will be arriving presently. But now you ought to come for breakfast as quickly as you can. The king sends word that your cocoa is getting cold.”

“But what about this?” said Princess, showing him her half-finished plait.

The master of ceremonies gave a look of despair. “I don’t know, how about something like this…” He handed Princess the red portfolio he was holding under his arm, and where the plait ended he tied the hair into a double fisherman’s knot.

“Wonderful idea, Master of Ceremonies!” said Princess, laughing, and she ran off to the dining room.

(Translated by Graeme Dibble)

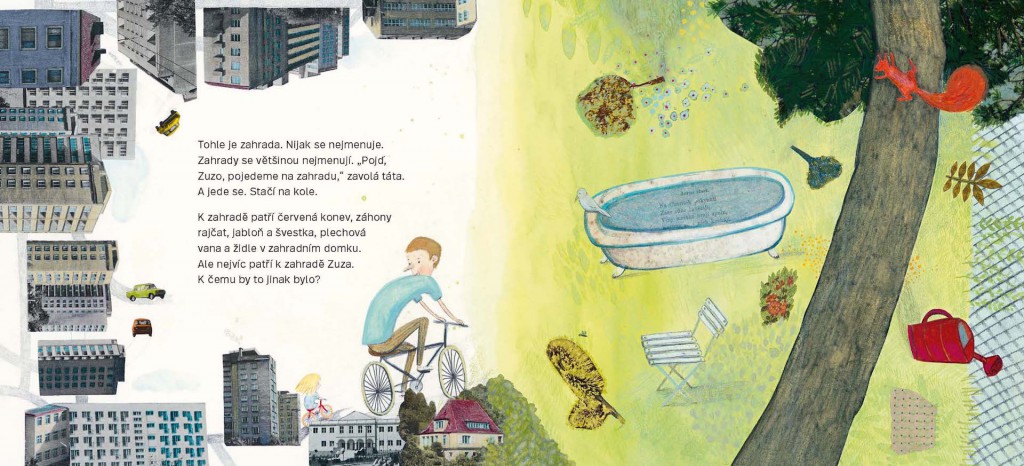

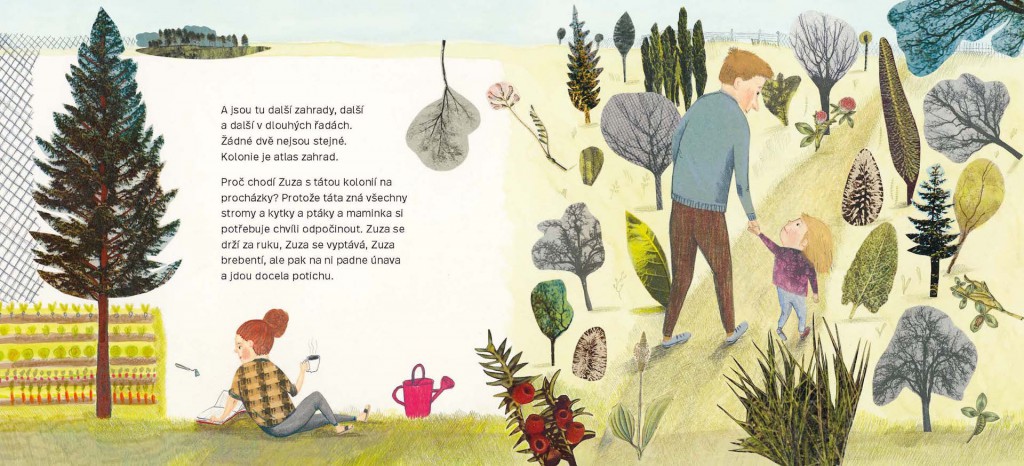

Jana Šrámková & Andrea Tachezy

Susie in the Gardens

Zuza v zahradách

(Labyrint/Raketa, 64 pages)

Age: 5+

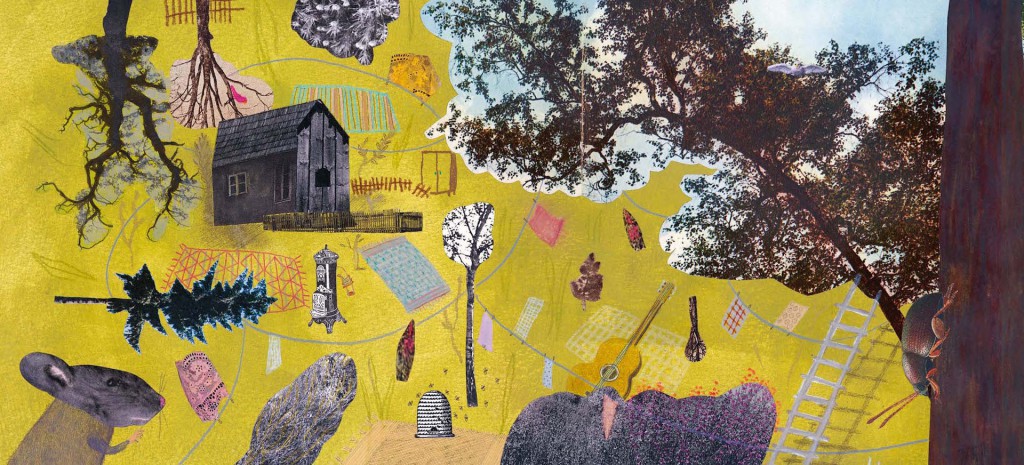

It is encouraging to see the many stories authored by young writers drawing their inspiration from nature and its various forms. Jana Šrámková sets her narrative about little Susie in an urban gardening colony. Although many such places have disappeared under new construction, the garden frequented by Susie and her parents is still inhabited by a colourful array of diligent vegetable- and flower-growers. One neglected plot of land, belonging to Old Bella and her black dog, sticks out from the rest. It looks appealingly dissolute and gradually reveals some of its secrets, which enter the sphere of the little girl’s dreams. Susie used to have a key to one of the garden’s trees – its name remains a mystery even to her peers, for whom the reading of this book will amount to a refreshing outdoors expedition.

Trailer

Praise

“Jana Šrámková has written a number of books for children showing her sensitivity for language and atmosphere. The short story Susie in the Gardens also displays a close connection with Andrea Tachezy’s illustrations: the result is a charming and exciting book which is especially suited for beginner readers.”

— Pavel Mandys, iLiteratura

Links

Publisher: www.labyrint.net

Illustrations

-

Excerpt ▼

This is the garden. It doesn’t have a name.

Gardens don’t usually have names. “Come on,

Susie, let’s go to the garden,” calls Dad.

And off they go. It’s not too far to cycle.

In the garden there is a red watering can,

tomato plants, an apple tree, a plum tree,

a metal bathtub and a chair in a garden shed.

But most importantly in the garden there is Susie.

Otherwise, what would be the point of it?

And there are other gardens here, more

and more of them in long rows.

No two of them are the same.

The allotments are like an atlas of gardens.

Why does Susie go for walks with her dad

around the allotments? Because Dad knows all

the trees and flowers and birds, and Mum needs

to rest for a while. Susie holds his hand,

Susie asks questions, Susie chatters, but then

tiredness suddenly hits her

and they walk along quietly.

(Translated by Graeme Dibble)

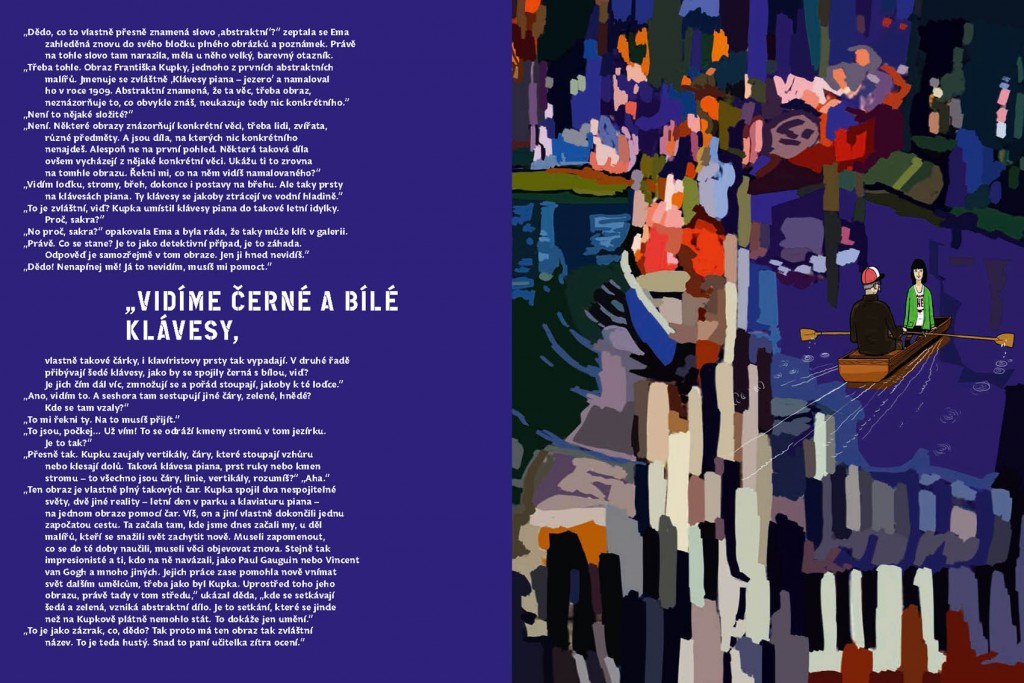

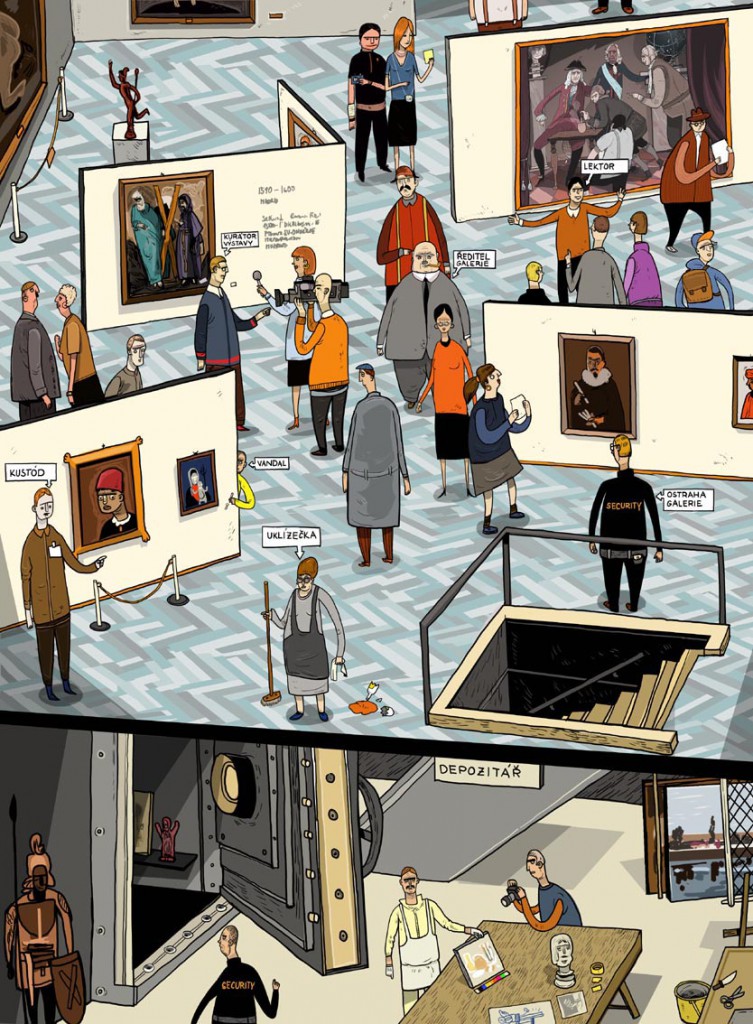

Ondřej Horák & Jiří Franta

Why Paintings Don’t Need Names

Proč obrazy nepotřebují názvy

(Labyrint/Raketa, 96 pages)

Age: 10+

One weekend Emma and Nick find out from their grandparents that the world “gallery” applies not only to contemporary shopping temples of consumerism, but also to friendly institutions, which accommodate children’s inherent need to ask, search and think. This year’s Magnesia Litera and Golden Ribbon-winning book uses dialogue-based prose, interlaced with gripping comic-book sequences, to turn exhibition spaces into frolicsome playgrounds that help humanise the forbidding sphere of “modern art”. An experienced advocate of art has joined forces with a notable protagonist of the comic-book circles to create a lovably condensed literary form, combining debates on art-history with light parody and live broadcast of a burglary involving Kazimir Malevich’s famous Black Square. The book includes information summarising main artists, schools, approaches, painting techniques, as well as some of the best-known cases of art theft, giving older school children a better understanding of why an original, and the originality of an artist’s vision, mean so much to us.

Praise

“This book can be more informative for readers than many general introductory texts about art history or theory.”

— Klára Kubíčková, idnes.cz

Awards

- 2015 Magnesia Litera – For children and youth

- 2015 Golden Ribbon Award – Art section: Non-fiction for children and youth

- 2015 White Ravens

Links

Publisher: www.labyrint.net

Illustrations

-

Excerpt ▼

“Granny, how are paintings actually made?”

“It’s quite simple. Artists normally use canvas or paper. But it doesn’t really make any difference – you can use anything you can paint on. You also need to have something to paint with: brushes, paints, maybe an artist’s palette. But you know what? That’s not really important – for example, you can make a picture in the snow with your finger, on the wall with spray paint or on the pavement with chalk. That’s not what it’s about. It’s about what you create. That’s the only thing that really matters.”

“And what about that stand Grandpa has in the cellar?”

“An easel. And a straw hat on your head, paint all over your hands… You know, that’s more just a notion people have about how an artist should look. The truth is that you don’t even need an easel. You can just put the canvas on the ground or on a table. What I mean is: there’s no such thing as the correct equipment or correct appearance for an artist. I know a painter who looks like an office worker, and an office worker who looks like a painter. Just take a look at that painting.”

“That painting’s so big that I can’t look at anything else anyway.”

“Jackson Pollock placed the canvas on the floor, threw away his paintbrush and poured the paint on straight from the tin. He created totally new works of art which continue to fascinate people today, and he didn’t need to have a beret on his head, or a palette, brushes or an easel.”

“That’s cool. But I’m afraid that when I move on from this painting to the next one I’ll forget about it. That after a while I won’t even remember that I saw it and how much I liked it.”

“It only seems that way to you. Powerful things remain inside you forever. And some works of art have that power. You have them inside you and they affect you without you even knowing about it. For the whole of your life.”

“Do you have them inside you?”

“Of course. But don’t think about it as if it was a roll inside your stomach.”

“Hmm, I don’t know, maybe there isn’t enough room inside me,” laughed Mikuláš, and he ran over to the handrail from which you could look down on the floor below and the whole of the gallery.

“You have to believe in it all at least a little bit, as a wise man once said,” added Granny.

(Translated by Graeme Dibble)

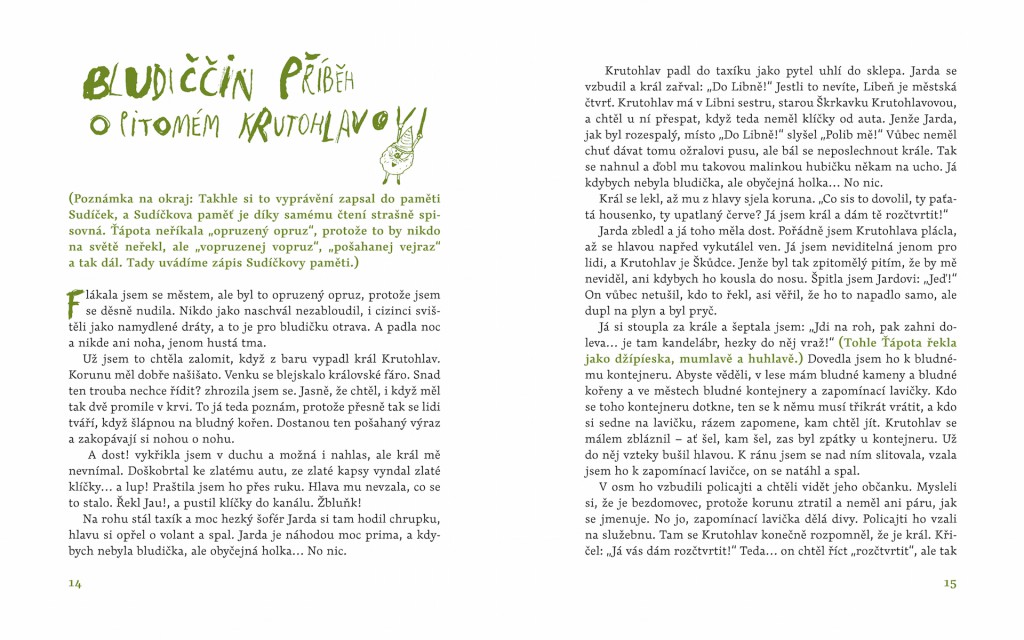

Daniela Fischerová & Jitka Petrová

Deformatory

Pohoršovna

(Mladá fronta, 120 pages)

Age: 8+

This original children’s story is a Golden Ribbon winner in the children’s prose category and draws on the current popularity of magic-school narratives, but transforms imported fantasy models through comically turning the tables. In the land of the despotic ruler Cruelhead there is a reformatory institution for maladjusted spooks who, rather than harming people, suffer from various embarrassing forms of niceness and perverse kind-heartedness. Unless the whip of Malefica Grudgeberth is quick enough to intervene, these beings could easily turn into doctors without borders or guide dogs. Recruiting from gabbling “dorcs”, “lampires”, who spend nights reading books, and the little-promising “imp in development”, will they eventually conform to the deformatory’s code of conduct? Only the Fairy Godson, an inconspicuous little boy, sees what is going on due to his soothsaying gift. Daniela Fischerová’s masterful use of language, supported by situation humour, a pleasant helping of disorderliness and Jitka Petrová’s dynamic illustrations, leads junior-school children to the conclusion that both people and fairy-tale creatures should strive for the reconciliation of our two worlds.

Praise

„An incredibly funny story which you will read in one sitting. The author, Daniela Fisherová, skilfully plays with the Czech language, she looks into the intestines of every word and transforms them into new, unexpected meanings which move the story forward.“

— Jana Vyskotová, Kultura21.cz

Awards

- 2015 Golden Ribbon Award – Literary section: Literature for children

- 2015 White Ravens

Links

Publisher: www.mf.cz

Illustrations

-

Excerpt ▼

The Will-O’-The-Wisp’s Story about the Idiot Cruelhead

(Marginal note: This is how the tale entered Moiris’s memory, and because of all the reading he does, Moiris’s memory is rather bookish. Wanda didn’t say “pain in the posterior”, because nobody would actually say that, but “pain in the butt”, “spaced-out expression” and so on. So here we present the account from Moiris’s memory.)

I mooched around the town, but it was a pain in the posterior, because I was bored stiff. As if to spite me, nobody went astray – even the foreigners zoomed along as if they were on rails, and that’s a nuisance for a will-o’-the-wisp. Night fell and there was no-one to be seen, just dense darkness.

I was ready to call it a night when King Cruelhead stumbled out of a bar. He was wearing his crown all lopsided. The gleaming royal wheels were parked outside. Surely that fool didn’t intend to drive? I was horrified. Of course he did, even though he’d had a skinful. I know that look very well, because it’s exactly the one people get when they step on a stray root. They get that dazed expression and start tripping up over their own feet.

Enough! I exclaimed in my head, and perhaps even out loud, but the king was oblivious to me. He staggered over to the golden car, took the golden keys out of his golden pocket and… Whack! I struck him across the hand. His head didn’t register what had happened. He shouted Ow! and dropped the keys into the gutter. Plop!

There was a taxi on the corner and its lovely driver, Jarda, was having fifty winks with his head resting on the steering wheel. Incidentally, Jarda is really great, and if I weren’t a will-o’-the-wisp but an ordinary girl… Oh, well.

Cruelhead fell into the taxi like a sack of coal into a cellar. Jarda woke up and the king roared: “Libeň, and quickly!” In case you don’t know, Libeň is a city district. Cruelhead has a sister in Libeň, old Roundworm Cruelhead, and he wanted to stay over at her place, since he didn’t have his car keys. But Jarda was still half asleep, and instead of “Libeň, and quickly!” he heard “Lean in and kiss me!” He had no desire to give that drunkard a kiss, but he was afraid to disobey the king. So he leaned over and gave him a tiny little peck somewhere on the ear. Now, if I weren’t a will-o’-the-wisp but an ordinary girl… Oh, well.

The king got such a fright that the crown slipped off his head. “How dare you, you gammy caterpillar, you grubby worm? I am the king and I will have you drawn and quartered!”

Jarda turned pale. I’d had enough. I gave Cruelhead such a slap that he rolled out head first. I am invisible only to humans, and Cruelhead is a Fiend. But he was so befuddled by the drink that he wouldn’t have seen me if I had bitten him on the nose. I whispered to Jarda: “Go!” He had no idea who had said it – he probably believed that it was his own idea – but he stepped on the gas and was gone.

I went up behind the king and whispered: “Go to the corner, then turn left… There’s a lamp-post there, bump right into it!” (Wanda said this in a muttering, mumbling voice like a sat nav.) I led him towards a stray skip. Just so you know, in the woods I have stray rocks and stray roots and in towns stray skips and forgetting benches. Whoever touches the skip has to return to it three times, and whoever sits on the bench immediately forgets where he wanted to go. Cruelhead almost lost his mind – no matter where he went, he found himself back at the skip again. He banged his head against it in his fury. Towards morning I took pity on him. I took him to a forgetting bench, and he stretched out and slept.

At eight o’clock the police woke him up and wanted to see his ID card. They thought he was a homeless person, because he had lost his crown and he hadn’t the faintest idea what his name was. Yup, the forgetting bench really does work wonders. The policeman took him down to the station. There Cruelhead finally remembered that he was a king. He shouted: “I’ll have you drawn and quartered!” That is, he wanted to say “drawn and quartered”, but he tripped over his tongue and ended up shouting something like: “Drrrnaw! Qrrtuard!” The policeman tapped their foreheads and this sent the king into a terrible rage.

Then Roundworm came to get him, and apparently she gave him a spanking right there in the police station, because she was the only one who wasn’t afraid of Cruelhead. She had looked after him when he was young, and she is also a Fiend, which means that the king couldn’t have her drawn and quartered. Oh yes, and Jarda turned the golden crown in to the police. It didn’t even occur to him to prise at least one ruby off it. Have I already mentioned that Jarda is great? Oh, I have. If I weren’t a will-o’-the-wisp but an ordinary girl… Oh, well.

Wanda Puts a Spell on a Chair

Moiris said: “That was a nice story!” But the will-o’-the-wisp stuck her tongue out at him and turned away.

The twins looked this way and that and didn’t know what to say. Murdalotte (a soft-hearted whimperer) whimpered soft-heartedly at the idea of her dear father banging his head on the skip, but deep within her belly there was a teensy little place where she silently giggled at it. Morvenge (a scaredy-cat with charitable tendencies) was afraid that his daddy would appear, perhaps fall down from the ceiling or crawl out of the wall, and have them both drawn and quartered. One of the dwarfs shrieked with laughter and covered his mouth with his hat.

“Wanda, do you know where we are?” asked Moiris.

Wanda slapped herself on the forehead to make it clear to him what a stupid question it was. The penny dropped and Moiris blushed a little. “Yeah, if you don’t even get lost at the North Pole, then you probably know.”

“Hey,” said Baby Yaga, “do those stray thingamajigs come into being by themselves, or do you make them?”

“The ones in the woods were made by other will-o’-the-wisps long ago and the ones in town are made by me. I can also make a stray chair or a forgetting mattress.”

“Show us! Show us!” begged the dwarfs.

“Yes, please, show us!” joined in Moiris.

“Go to hell, you know-it-all!” said Wanda, pulling a face. Then she changed her mind: “All right then. But everybody has to close their eyes. It’s my trade secret and I don’t want anybody watching me at work.”

“It won’t do any good with me,” said Baby Yaga. “We witches can see even with our eyes closed. But I’ll look up at the ceiling.”

(Translated by Graeme Dibble)

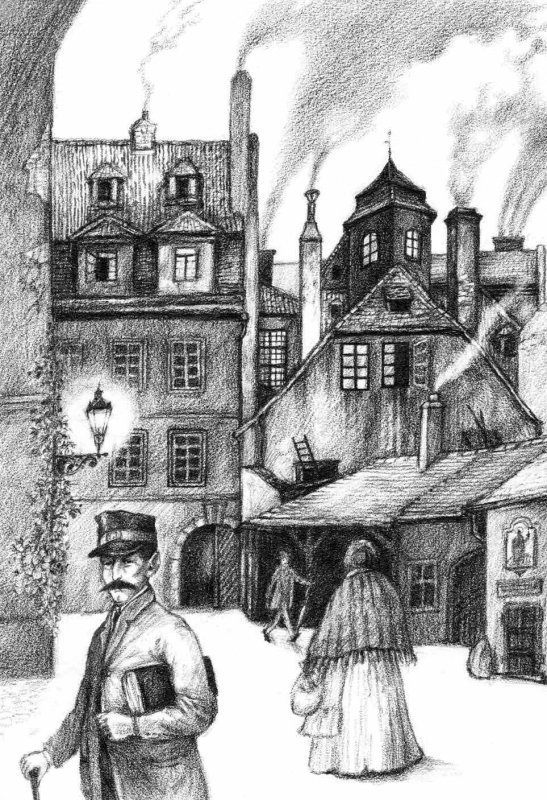

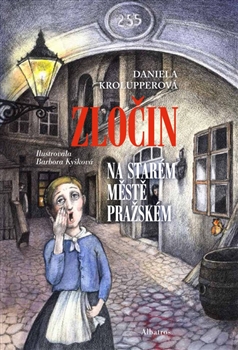

Daniela Krolupperová & Barbora Kyšková

A Crime in Prague’s Old Town

Zločin na Starém Městě pražském

(Albatros, 144 pages)

Age: 10+

Historical crime stories for curious children appear rarely on bookshop shelves, but this one may also serve as an attractive book about Prague. The plot, set in old Prague, draws inspiration from Jakub Schikaneder’s well-known painting Murder in the House, skilfully rendered in Barbora Kyšková’s illustrations. Little Jakub witnesses a girl’s tragic fall from a balcony, returns home disturbed, and never forgets the dreadful scene. Meanwhile, Detective Inspector Zastávka questions many witnesses – a showcase of socialites of late 19th century Prague, by then a somewhat sidetracked metropolis. Daniela Krolupperová smoothly incorporates real people and events into her text, making sure that school-age readers of this Golden Ribbon-winning text will learn not only who the perpetrator of the crime was, but also how the sports organisation Sokol and the first grammar school for girls Minerva came to exist.

Praise

“A Crime in Prague’s Old Town is both readable and informative”

— Jitka Zítková, iLiteratura

Awards

- 2015 Golden Ribbon Award – Literary section: Literature for youth

Links

Publisher: www.albatrosmedia.cz

Illustrations

-

Excerpt ▼

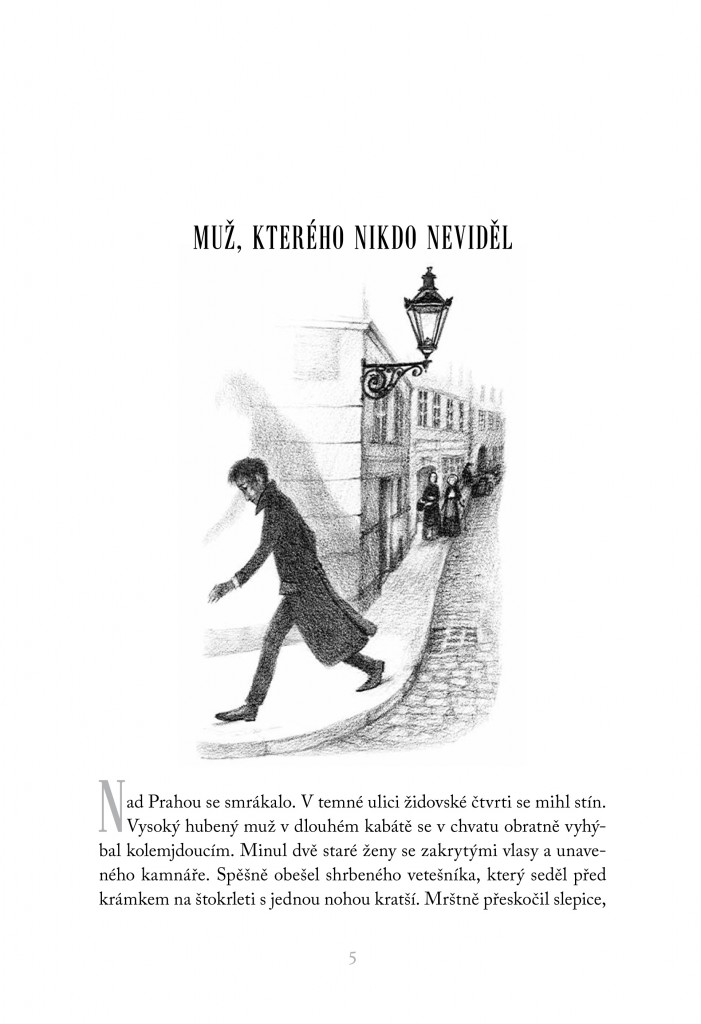

The Man that No-one Saw

As dusk was falling over Prague, a shadow flickered in the dark streets of the Jewish quarter. A tall, thin man in a long coat hurried along, deftly avoiding passers-by. He skirted round two old women with covered heads and a tired stove fitter. He dashed past a hunchbacked rag-and-bone man who was sitting in front of a shop on a stool with one leg shorter than the others. He nimbly jumped over a hen which was happily pecking at some sewage spilled over the cold cobblestones. He dodged wheelbarrows filled with vegetables and a staggering drunk in a paint-spattered overall.

He ran through the narrow streets with their dark, musty houses. His echoing steps boomed as though they were harbingers of evil. He kept his face lowered so that it was impossible to see his eyes. However, if someone had looked into them, they would have seen a silently screaming terror within them. He was nervously clutching something in his clammy right hand.

He ran out of Rabín Street and along Hampejská. He stopped for a few seconds outside the pub U Denice, as though debating whether or not to enter. Or perhaps he only needed to catch his breath. He continued on at almost full pelt. At one critical moment the object he was tightly grasping glinted in the twilight. From the rich lustre it was clear that it was a bar of gold.

No-one had any inkling that he had left the house at number 255 Rabín Street that afternoon. And no-one was ever supposed to find out, because death had entered the house that day, and he was the one who had invited it in.

Mother was just clearing the table. Karel disappeared outside again; his friends were whistling for him from below the window. Kuba remained seated. He took out a piece of paper. There was still some space in the bottom right corner. He already knew what he would draw. He had been thinking about it all the time he had been eating. A horse. The kind that Váchal the carter had. A skewbald. Pawing the ground with his front leg.

Kuba was two years younger than Karel and completely different in character. He didn’t like to fight. He was too small in build and could be easily knocked about, although if it came down to it, little Kuba would slug it out stubbornly till his last breath. He never gave up.

Mother tidied up the kitchen. A quiet atmosphere of contentment filled the house. Father was at work and Karel was outside. Kuba tried to imagine the precise appearance of the horse’s leg, but he couldn’t do it. Lost in thought, he chewed away at his pencil. How come I don’t know when I see the horse every day? he said to himself rather crossly.

The leg he had sketched stood out unnaturally from the horse’s body. The drawing was going badly. Kuba frowned. Mother came up to him and leaned over the picture. She smiled and patted the boy on the head. He would completely fill each piece of paper with his drawings. She knew that his constant urge to draw was due to his talent – a talent which he most likely got from her late brother Toník. She never skimped on buying paper for little Kuba, even though it was expensive.

“You should probably bend the leg downwards, like this,” she advised her son, showing him with her finger the direction of the stroke. “But otherwise the horse looks very real.”

But Kuba just frowned even more. It made him angry when he wasn’t able to draw what he wanted. He pushed the chair sharply away from the table so that it scraped noisily along the wooden floor. He jumped up and had a good mind to scrunch up the paper and throw it away. However, the paper cost a lot of money and there was still some space on it.

“It’s all wrong!” he shouted.

“That doesn’t matter. The next one will turn out better!” Mother had a kind and gentle voice.

“I ruined the whole thing” said Kuba furiously.

Mother put the plates into the dresser and came back over to Kuba. She patted him on the head again.

“You have to be patient,” she said pleasantly.

But Kuba just frowned and said nothing. He wasn’t at all patient, and more than anything he couldn’t stand it when his drawings were going badly. He got very annoyed with himself.

“I’m going to run over to the carter’s to have a look,” he finally announced to his mother, because despite his best efforts he couldn’t recreate a living horse in his imagination.

“OK,” agreed Mother, “But don’t be long!” She handed Kuba his short jacket and his cap. “And be careful,” she added, as always.

Kuba rushed out of the door to his house on the corner of Dlouhá and Hradební Street. The Schikaneders were Catholics. Kuba had been christened by the priest in St Jakub’s church, which was very near the house where the family lived. It wasn’t at all unpleasant to live at the edge of the Jewish quarter in the Old Town. There the Catholic and Jewish worlds encountered each other in a peaceful, kind and conciliatory atmosphere. The neighbours knew each other and got along together without any problems. Everyone had their place here.

Kuba ran to the carter’s, but when he got there he discovered that Mr Váchal was away with his cart.

Fury smouldered within Kuba. How is it I can’t remember exactly what a horse’s leg looks like? he raged inwardly. He knew that he wouldn’t find peace until he had drawn the horse properly. And now he was to leave empty-handed? No way!

He carried on into the Jewish quarter. But, of course, they’ve got horses here too! In autumn Katz the coalman hired a whole team of them for delivering coal. Kuba was pleased that he had remembered this and quickened his pace.

He ran along Hampejská Street and down into Rabín to the courtyard of house number 255. However, there were no horses to be seen, although there was a large red admiral butterfly on the wall beside the gate. This was odd as it was autumn and butterflies no longer flew around the city. But before Kuba could get a better look at the multicoloured butterfly, something plummeted onto the stone cobbles beside him. There was the sound of a dull thud. It was all over in an instant.

Right in front of Kuba on the cobbles beside the gutter lay the body of a pretty young woman. Her arms stretched out limply. Bright red blood had begun to flow around her head. There was no doubting that she was dead. She must have fallen from the courtyard gallery.

Kuba froze. He was paralyzed with fear. He stared breathlessly at the girl’s gentle face stained with blood and at her thick hair, which had come undone from its ponytail and now spread around the girl’s head like a mysterious halo. It was quickly becoming matted with blood.

Then someone knocked into Kuba so forcefully that he fell to the ground. It was only when his head struck the cold cobblestones that he became aware of people in the courtyard. Until now no-one had spoken, but all of a sudden there was motion everywhere. Footsteps clattered on the cobbles.

“Muuurder!” screamed a woman.

And then another squeaky, equally high-pitched voice: “Muuurder! Heeeeelp!”

“Anežka!” roared a man’s deep voice.

“Police! Call the police!” added another woman.

“My dearest Anežka!” came the muffled voice of a younger woman, breaking into a desperate cry.

Voices shouted out at the same time, merging into one confused din.

Kuba got up. His head hurt from his fall and for a very brief moment he couldn’t see anything. When he regained his sight, he tottered out of the courtyard. In the growing confusion no-one noticed him. He hadn’t even made it to the next house when he started to be sick.

This gave him some relief, so he was able to continue on his way. He would have liked to run, but it was impossible. His body felt weary and strangely numb. He didn’t notice the piercing whistles of the policemen. He left 255 Rabín Street without even realizing that there was blood coming from his knee, his right forearm and his temple. He didn’t notice how much it hurt until he bumped into a tottering figure.

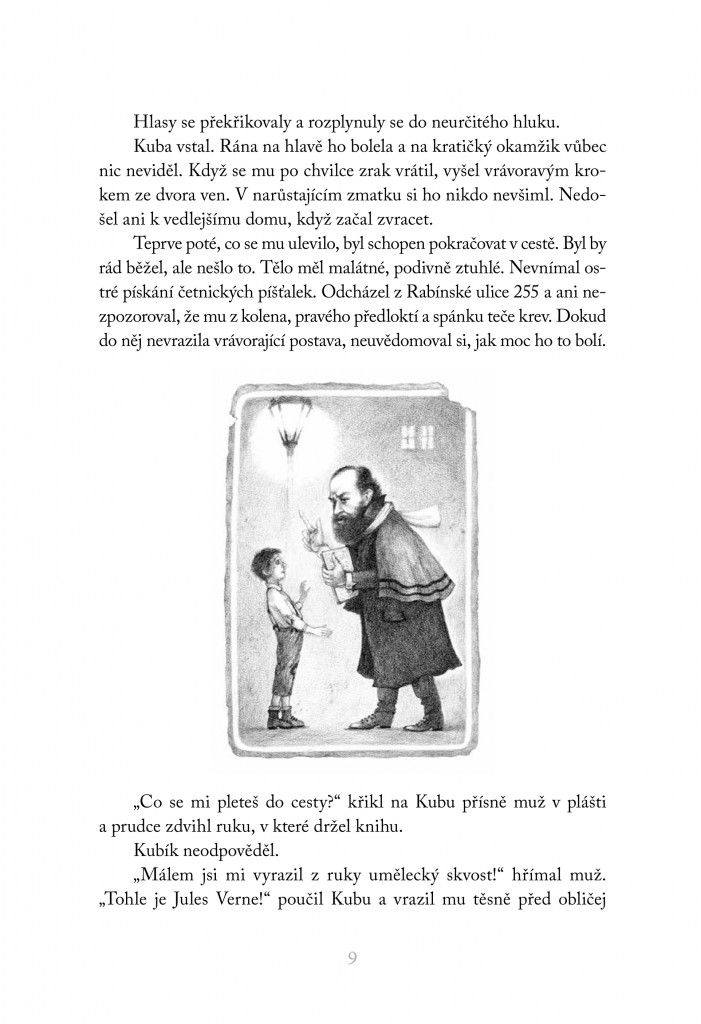

“What are you doing, getting in my way?!” shouted the man in the overcoat sternly. He abruptly raised his hand, which was holding a book.

Kuba didn’t answer.

“You almost made me drop this artistic gem!” he thundered. “This is Jules Verne!” he said, lecturing Kuba, and thrust the large novel in front of his face. “A great artist of the new age! Cinq semaines en ballon, you rapscallion!”

The man fell silent for a moment and frowned. Then he shook his head as though he were quarrelling with someone and waved his arm in a bitter gesture: “But no-one here knows anything about him! Of course not!”

Kuba stared breathlessly at him.

“No-one here appreciates real art. Prague is a European outpost, the less said about it the better,” said the man, continuing his lamentation. Then he looked at the boy, who was scared to death, and realized that the child couldn’t understand what he was saying. “Be off with you then, boy!” he finally shouted.

He turned round and continued walking to the Unionka Café to persuade the publisher Vilímek to bring out his book in Czech. He was fairly certain that he would have no luck. In fact, Neruda had got used to being shown the door…

Kuba shot off home. Suddenly he was able to run again.

Just as Mother was beginning to wonder whether to go and look for her son, Kuba finally returned. Terrified and exhausted, he embraced his mother tightly at the doorway. His trouser legs were torn and the blood had started to dry on his knees. His forehead was scraped, the right temple covered in blood, and he also had dried spots of blood on his arm.

“Good Lord, what happened to you?! Who were you fighting with?” asked Mother in alarm. She carried Kuba into the kitchen – even though he was already big and heavy.

“I wasn’t in a fight. Somebody bumped into me,” explained Kuba, confused. “I fell and hurt myself. I can’t remember. A strange man threatened me with a book.”

Mother didn’t waste time and immediately began to heat some water on the stove so that she could wash Kuba properly and clean out his wounds. That was important, even if it did hurt like the devil.

Kuba cried. He had a fever and was asleep before Mother had carried him to bed.

Even after a few days, when the fever had passed, Kuba was still unable to recall what had happened that day. For the life of him, he couldn’t remember. But despite that, he never forgot.

(Translated by Graeme Dibble)

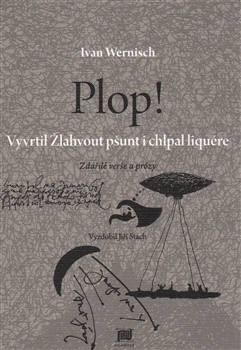

Ivan Wernisch & Jiří Stach

Plop! The Lebott’s Korc Unscrooed, He Upguzzeled Liqueur

Plop! Vyvrtil Žlahvout pšunt i chlpal liquére

(Meander, 56 pages)

Age: 12+

Works by Czech State Award for Literature laureate Ivan Wernisch, who entered the field of literature half a century ago along with his peers Petr Kabeš, Antonín Brousek or Pavel Šrut, have two characteristic modes. While the first is tinged with existential sadness, the joyful sources of inspiration of the second one spring from 20th century more and less avant-garde movements. The latter is also typical of Plop!’s “fine verse and prose”, in which the author parodies people who are close to him as well as the general ignoble circumstances, but most importantly of all re-imbues contemporary Czech poetry with original humour full of smirk, slyness and linguistic combinatorics embodied into neologisms. We can reasonably suspect that the poet’s mystifying playfulness, akin to Christian Morgenstern’s grotesque texts, in combination with Jiří Stach’s pictorial “embellishment”, will prove especially charming for adolescent readers seeking to transgress the boundaries of language in search of an unrestrained form of expression.

Praise

“Jonathan Swift … Lewis Carroll … Václav Havel … As you can see, the roots which feed Wernisch’s Plop are very deep and widespread.”

— Michal Žák, BrnoŽurnál

“The book is intended for clever children and adults who never stopped being children.”

— Petr Šmíd, A2

Links

Publisher: www.meander.cz

Illustrations

[ ]

The editors would like to thank Jana Čeňková, co-creator of the Best Children’s Books project, for materials and assistance.