In recent years, the detective, crime and thriller genre has been experiencing a boom in Czechia. New Czech authors have appeared whose books touch on contemporary reality and carefully outline the psychological profiles of their characters, while disrupting and updating the well-established pattern of murder – investigation – smart detective – surprising denouement.

The most popular form of light reading

Detective novels have always been very popular with Czech readers, and since the 1960s, when the communists allowed them to be translated again, they have been fortunate in having excellent (Anglo-Saxon) translators, with Jan Zábrana at the forefront. During the period of communist censorship it was one of the few gripping styles of fiction that was tolerated (unlike horror and fantasy, which were completely ignored). Detective novels had print runs of anywhere between 10,000 and 100,000 copies, and readers did not have to wait too long for the translation to come out.

Czech authors tended to take these translated works as their model, and for a long time they struggled with their own local setting, which seemed too sedate for sophisticated and exciting crime stories. Most of the writers initially set their novels abroad or wrote them under English pseudonyms such as Edgar Collins and Leon Clifton. For example, the first detective novel which Eduard Fiker – one of the most prolific (and certainly one of the best) writers of crime fiction – set in Czechoslovakia was his thirty-first book, Her Game (Její hra) from 1939.

Eduard Fiker. Photo source: Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University in Prague.

The first and for a long time the only person to successfully marry the detective novel with a Czech setting was Emil Vachek, who also created the first Czech detective to feature in more than one book. However, the patient and insightful Inspector Klubíčko only appears in three of his classic novels: The Portrait Gallery Mystery (Záhada obrazárny, 1929), Man and Shadow (Muž a stín, 1932) and A Minute of Evil (Zlá minuta, 1933). Although the author brought the character back at the start of the 1960s, the tales of espionage he featured in were weaker, simply “churned out” by Fiker. However, towards the end of his life he managed to write another three novels featuring the believable character of Major Kalaš, who for a socialist policeman was not overly encumbered by ideology (though more so in The Golden Four (Zlatá čtyřka), the opening novel, from 1955). Thanks to their momentum and tension, Fiker’s books represent some of the best Czech thrillers, worlds apart from the usual tranquil atmosphere of the popular “neighbourhood” short stories by Karel Čapek and Jiří Marko or indeed the majority of books published in this country.

During these years, Czech crime fiction followed the model of the traditional British whodunnits with their calm investigations by amiable police officers. In any case, private detectives did not exist in a country governed by communism. In addition to this, for forty years (1948–1989) authors had to reconcile themselves to the reality of a totalitarian police state which carefully monitored their work to see if the propaganda image of its repressive elements had been challenged or even maligned in literature (and in art generally).

Detective novels for elderly and less-demanding readers

After the fall of the communist regime in 1989, it appeared that interest in the escapist genre of crime had waned, but it was more that it had fallen off the media radar: thrillers by Pavel Frýbort or the more traditional detective novels by Eva Kačírková and Inna Rottová, writers who had started to publish either in the late 1970s or in the 1980s, still continued to sell relatively well. For example, thanks to the enormous success of Currency Speculator (Vekslák, 1988), Frýbort published 14 novels (mainly action or political thrillers with convoluted plots) between 1990 and 2007. At the same time, however, the Czech crime-fiction genre began to fall into obscurity slightly. There was pressure from translated works, which now offered popular classics alongside new names and subgenres which were more dynamic and dramatic – usually from the Anglo-Saxon world. By the end of the 1990s, older Czech authors gathered under the wing of the Brno publishers Moravská Bastei (MOBA), whose success was based on the high number of titles published each year as well as the deliberate targeting of less demanding readers who wanted crime stories to provide them with some light reading and saw them as something between a crossword and a fairy tale for adults. However, the publishing house was also restricted by this readership: they were mainly older readers who were not looking for any experimentation and preferred to read loose series such as Murder at the Spa (Vražda v lázních). These people also make up the main readership of MOBA’s most successful current author, Vlastimil Vondruška, whose trivial detective stories from the Middle Ages directly correspond to their taste: they are sedate, straightforward and short.

However – no matter how surprising it may seem today – when MOBA tried to present the more hardboiled Norwegian writer Jo Nesbø to its readers through its translated editions in 2005 and 2008, it was a complete failure. It must have been a great surprise for the owners when the rights for his books were released to a new publishing house, Kniha Zlín, and they went on to enjoy enormous success with him in 2011.

The Scandinavians are coming

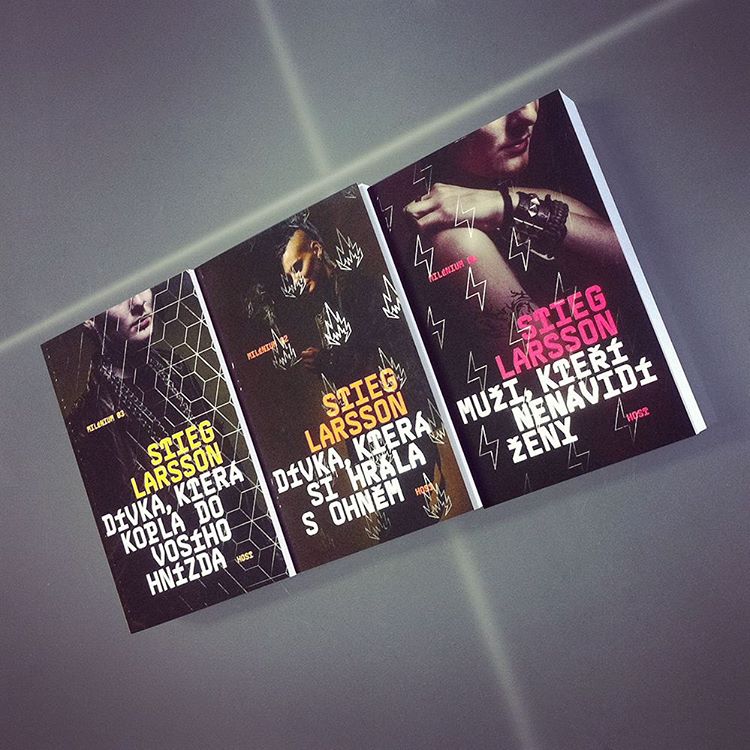

Jo Nesbø capitalized on a new wave of interest in Scandinavian crime fiction which began with the Swedish writer Stieg Larsson and his novel The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. This was brought out in Czech by Host publishers, who had previously concentrated on more demanding contemporary Czech prose, poetry and literary criticism. Because of this, the literary critics, who traditionally monitor Host’s output very carefully, also started to take an interest in Larsson and were quickly followed by the mass media. With this, Larsson also came to the attention of a different readership than the one MOBA had previously appealed to with its light-reading fiction. It was not that the other two novels in the Millennium series had much in common with realistic prose (unlike the first one), but more that the detective genre had suddenly been discovered by young, educated readers. The books also became fashionable with intellectuals and even managers – or more precisely with female intellectuals and managers, because an important element of Millennium’s success was that the series appealed to a female readership, which is key for fiction. Larsson came up with an unconventional heroine who is a computer whiz, can defeat two experienced brawlers with her bare hands and can rise from the grave after being shot in the head (which makes her more of a comic-book superhero) – all of which helped to attract female readers between the ages of twenty and forty.

The Czech edition of the ‘Millennium’ trilogy. Photo: Nakladatelství Host.

His success with this readership also had a knock-on effect for his fellow Scandinavians, even though this Scandinavian wave did not bring anything fundamentally new to the crime genre. But at least some of these authors managed to inject the popular crime novel with phenomena which were the focus of media attention at the time, including corruption, racism and domestic violence. They do not shy away from lengthy and complex stories, the psychological examination of the characters, action scenes, extremely brutal crimes or intimate dialogue – in the best cases, all of these are thrown into the mix.

The popularity of Scandinavian detective novels also showed that even the countries with the best quality of life and the lowest crime rates in the world can produce believable, dramatic stories about sadistic murders with ambiguous endings. The younger generation of Czech authors (and their publishers, of course) have shown that the atmosphere of American metropolitan life is not essential for readers. The Czech Republic has also demonstrated itself to be a sufficiently realistic setting: business elites and politicians very quickly became associated with organized crime, while the reputations of the police force and the justice system have also been tarnished by countless scandals in the media.

Crime and postmodernism

All of this ferment contributed towards a renaissance in the detective genre amongst Czech writers. And in recent years a number of new, mainly young authors have appeared who have greater ambitions than merely helping the reader kill time at the beach or spa. This is probably the only common denominator as otherwise it is impossible to find many shared themes. They have obviously been brought up on the current trends influencing the contemporary detective novel, which is more like a social critique than an adult fairy tale; however, each of them approaches it in a slightly different way. Although their books are certainly not in the same league as the world’s best detective novels, they stand up against other above-average works in an international context. Young authors are no longer ashamed to publish detective fiction as their debut work, especially when these are novels which happen to have a crime-centred plot rather than the traditional whodunnit with a murder at the start and the detective triumphant at the end. In many cases they lack skill in their craft and the reader identifies the culprit too soon. The portrayal of the characters becomes more important than the plot and the subject matter is toned down, as though a large number of corpses and brutal crimes did not belong in a Czech setting.

At the moment, crime fiction is one of the liveliest genres in Czech literature and also attracts mainstream writers. Perhaps the very best and boldest at handling the plots and techniques of the crime genre is Miloš Urban (who is not one to shy away from a high body count and extremely bizarre murders), even though his postmodern books cannot exactly be categorized as crime fiction – with the exception of the full-blooded detective novel She Came from the Sea (Přišla z moře, 2014), which contains clever plots and unpredictable characters reminiscent of Patricia Highsmith. The satirical thrillers The Mafia in Prague (Mafie v Praze) and A Frost from the Castle (Mráz přichází z hradu) by Michal Viewegh were weakened by the author’s desire to comment on actual events in Czech politics. In her novel Tsunami Blues, Markéta Pilátová introduced a spy story in the style of Graham Greene. Crime (and in part espionage) motifs are also central to the three-part series Out in the Sticks (Kde lišky dávají dobrou noc) by Chaim Cigan (pseudonym of the writer and rabbi Karol Sidon).

Markéta Pilátová. Photo: Jiří Sobota.

New discoveries

So who are the bright young things in Czech crime fiction? The first person deserving of a mention is Michaela Klevisová (born 1976), who published her first detective novel The Steps of a Murderer (Kroky vraha) in 2007. As with the subsequent book, The Story Thief (Zlodějka příběhů, 2009), it is a very traditional detective novel with a police investigator and suspects, who in the case of The Story Thief find themselves enclosed within an isolated rural setting. However, Klevisová’s next detective novel, The Secluded House (Dům na samotě, 2011), marked a shift in emphasis: the character of the police commissioner is made almost irrelevant while the role of the individual suspects becomes more important. Instead of searching for the culprit behind a double murder, Klevisová plays around with a psychological thriller in which the different ambitions of the characters frequently clash. Each has a secret – usually a plan to acquire something important (money, stature or a partner). Although the novel ends with the uncovering of the perpetrator, the reader is at least as interested in whether and how the plans of the other characters come to fruition.

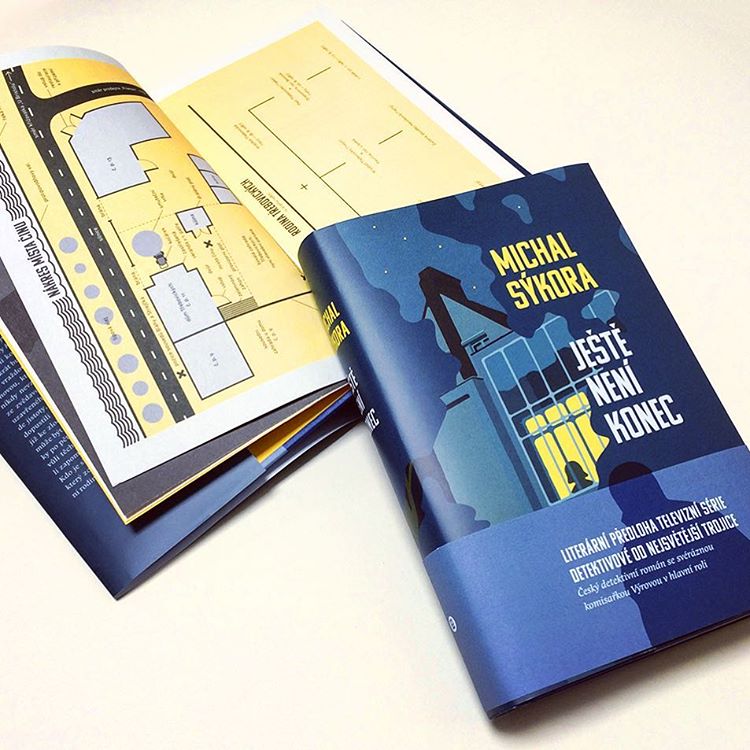

Character psychology is also the strong point of another distinctive contemporary figure from the Czech crime-fiction scene, Michal Sýkora (born 1971). The writer – literary critic, lecturer at Olomouc University, author of a two-part literary monograph on Vladimir Nabokov and two other literary-history studies – surprisingly published a detective novel in 2012 entitled A Case for an Exorcist (Případ pro exorcistu), to which a further two novels were added: Blue Shadows (Modré stíny, 2013) and It’s Not Over Yet (Ještě není konec, 2016). All of these books feature a team of Olomouc detectives led by Commissioner Výrová, and Sýkora carefully constructs the private and professional backgrounds of her and her colleagues. This also plays an important role in Blue Shadows during the search for the murderer of a university professor, as the (partly calculated) behaviour of a spurned police officer begins to undermine the entire investigation. A Case for an Exorcist alternates between the humorous twists and turns of an investigation in a typical Haná village and the dark case of a brutal murder. This does not serve the atmosphere of the novel particularly well, but the result is a traditional detective novel which is solid, exciting and believable and keeps the reader guessing to the end. It also contains many of the elements used by contemporary international authors, in particular the attempt to get as close to reality as possible. In contrast, Blue Shadows is more of a political thriller about corruption and politics, even though at first it seems to be a crime story set in a university. Gelnar is a caricature of a former minister of the interior, Ivan Langer, whose integrity was often questioned by the Czech media, while the villainous bursar at Olomouc University was also inspired by a real-life character. Sýkora manages to keep all of this within the confines of his fictional novel and does not try to explicitly castigate all the abuses as Michal Viewegh had done before him. Sýkora also attracted the attention of Czech Television, which has taken a long-term interest in the crime genre (with at best fluctuating success), and the result was a three-part series The Detectives of the Holy Trinity (Detektivové od Nejsvětější Trojice).

Michal Sýkora’s ‘It’s not over yet’. Photo: Nakladatelství Host.

Writing the script for the television series The Zodiac Murders (Vraždy v kruhu) also represented a new departure for the famous author of children’s books Iva Procházková (born 1953). While the series was being shown, she also published her first detective novel, Man at the Bottom (Muž na dně, 2014), which was a prequel to the series. The clever, believable, expertly structured and unusual plot is one of the best to have appeared in Czech crime fiction in recent years. The reader does not only follow the case from the perspective of the investigator, but also finds himself rooting for some of the suspects and searching for someone else who might fit the description of a cold-blooded murderer. But there is no such person, because the only truly monstrous villain was the murder victim. This brings another new element to the Czech crime genre: the murder victim as a classic example of a corrupt policeman, who besides indiscriminate extortion also drank, took drugs and raped the women he had in his power. After finishing the book the reader feels sorry for the characters who had to pay so dearly for such minor misdemeanours.

Newcomers to crime

Over the past three years, several authors have appeared who have chosen the crime genre for their literary debuts. B. M. Horská is the pseudonym of an author living in England who adheres to the style of the modern classics from the British school of P. D. James and Ruth Rendell. Her novel The Smell of Death (Pach smrti) incorporates Czech elements into a British setting in an inventive yet natural way (the murder victim is a Czech biologist with links to a university in the small English town where she lives as well as a university in Czechia), while the thriller-style finale is a vain attempt to improve a rather unsurprising denouement. In her other novels, her British detective of Czech extraction, Ellen Jolly, travels to unusual destinations in Europe: to the Finnish island of Ukko Kokko in her novel The Beetle (Brouk, 2014), and to Sicily in the novel Gloves of Death (Rukavičky smrti, 2016).

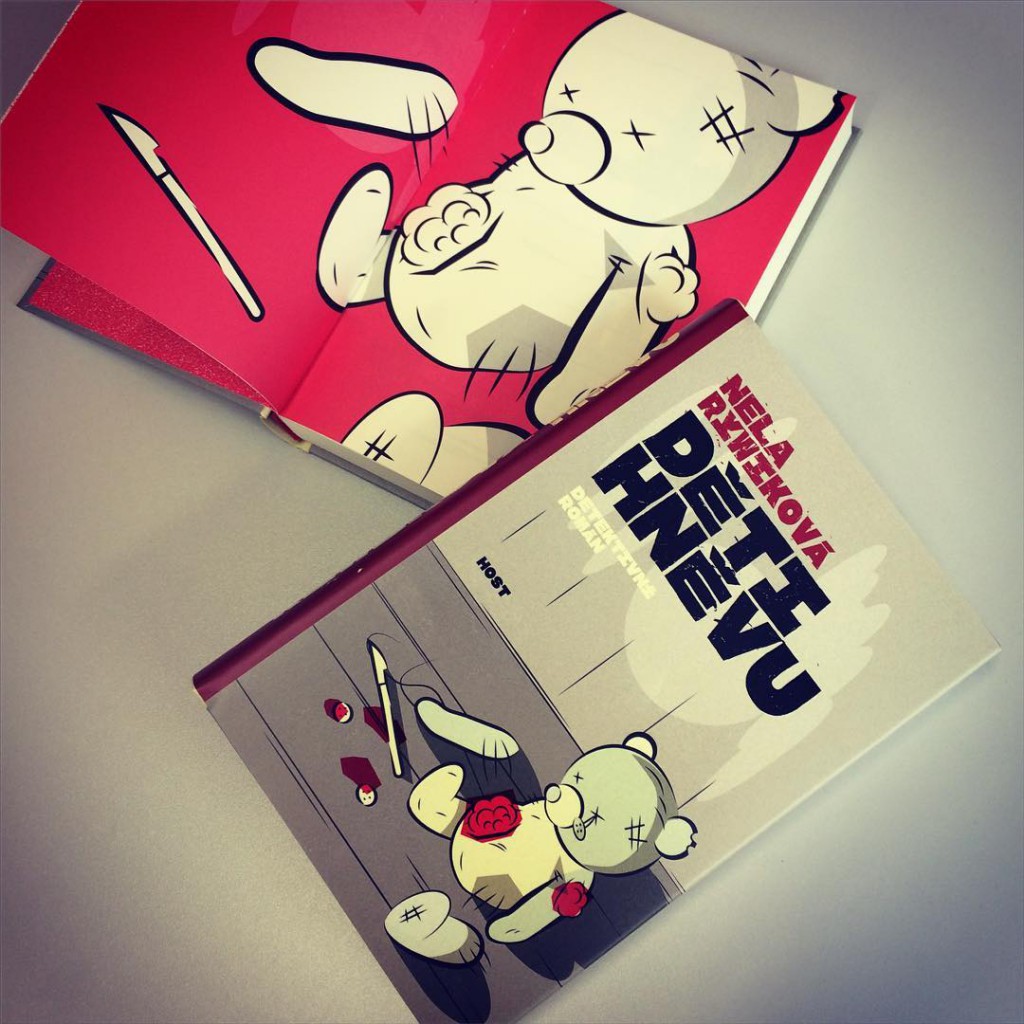

In contrast, Nela Rywiková (born 1979) set her novel House Number 6 (Dům číslo 6, 2013) in a rundown area of the former industrial town of Ostrava, and the story centres on the conflicts surrounding an apartment building which is threatened with demolition. Her crime fiction has a strong social element, though nothing as superficial as poor tenants suffering due to pressure from developers, and it is also very well structured. The author presents the tenants in the threatened building as fatalistic, selfish and dimwitted people, and even the murder is not the work of a clever, sophisticated killer. However, this does not detract from its horror. Her next novel, Children of Anger (Děti hněvu, 2016), is again based on the author’s local knowledge (linking the poorest people with the local business and political elites). It has a solid plot with a horrible discovery at the start, well-drawn characters who have something to hide, and a devastating climax, which is extremely uncharacteristic of Czech detective novels.

Nela Rywiková’s ‘Children of Anger’. Photo: Nakladatelství Host.

One problem with Nela Rywiková’s work is its literalism. The same can also be said of another interesting debut by Jiří Březina (born 1980), On the Hill (Na kopci, 2013). The novel begins with an investigation into a supernatural phenomenon (an angel appearing to a schoolgirl), but then gradually turns into the search for a criminal. Again, Březina’s strength lies in character psychology and in constructing individual scenes rather than the main storyline. Following the conventions of the genre he spends a long time sending the reader on false trails, but after the identity of the culprit is revealed two-thirds of the way through the book, the remainder is then devoted to two people (an ex-policeman and a university student) trying somewhat laboriously to find a way to convict him. It is a pity that the newcomer’s manuscript was not entrusted to an experienced editor as the result could have been an excellent psychological thriller.

In his subsequent novels the author appears to be more knowledgeable and technically adept – Time-barred (Promlčení, 2015) concerns an old murder case in the mountains of a border region, where the culprit is not revealed until the end and over considerably fewer pages. Time-barred also features a young police inspector whose next case is in the subsequent novel The Noonday Witch (Polednice, 2016), which would suggest that the author is attempting to produce a series with the same investigator.

Hardboiled realism in a Czech setting

Martin Goffa is the pseudonym of a former policeman (born 1973) who has already written six novels and one book of short stories in quick succession. His first two books, The Man with the Tired Eyes (Muž s unavenýma očima, 2013) and A Christmas Confession (Vánoční zpověď, 2013), offered a convincing psychological profile of a criminal and his crime. In the case of The Man with the Tired Eyes, this develops rather artificially from a haphazard take on the detective novel with a policeman as the main character. A Christmas Confession has a better structure; once again, the all too obvious intention is to defend an unfortunate man whose desperation leads him to take revenge on a fraudulent moneylending firm. But in both cases there is a valuable analysis of the Czech underworld (including the fact that the culprit in The Man with the Tired Eyes is Ukrainian), which demonstrates that the author is familiar with this material from his previous occupation. He also draws on this in the pitaval The Living Dead and Other Police Stories (Živý mrtvý a další policejní povídky, 2015). The main series featuring the detective Mike Syrový – who we first meet when he has left the police force, although he later returns to his outfit – is a Czech variation on the hardboiled crime novels by American authors.

But true hardboiled realism did not arrive in Czech literature until 2015 with the novel Quick-fire (Rychlopalba). Its author, Štěpán Kopřiva (born 1971), had previously published exceptionally brutal action novels incorporating parody and very dark humour with elements of sci-fi and fantasy. The beginning of Quick-fire is initially restrained as its main character, an ordinary policeman, takes up a previously abandoned search for a twelve-year-old girl. Gradually, however, the action intensifies and the unnamed investigator begins to break both service regulations and the law – from breaking into a rural cottage to shooting four people. However, he is not a corrupt police officer; he just has to solve the case using his own distinctive methods, and when it is all over he remains an outsider without any recognition or promotion. In the best traditions of hardboiled realism, the author blends together two mutually unconnected cases. Neither of these is brought to an entirely satisfactory conclusion for the characters and even the reader shares that bitter “noir” feeling with them.

A detail from the cover of Štěpán Kopřiva’s ‘Quick-fire’.

Most of the new authors in Czech crime fiction need time (and perhaps also editorial guidance) in order for their writing to mature. They have mastered the art of shortcuts, exaggeration and a dispassionate overview, as well as some of the stylistic tricks and subterfuges used by authors in thrillers. Their attempts so far have also been very valuable due to the natural and confident way they introduce motifs and elements of contemporary reality into the somewhat artificial environment of Czech crime fiction, including social tension, avaricious materialism in interpersonal relationships and the unpunished machinations of white-collar workers.

Translated by Graeme Dibble

Cover image: An illustration by Martin Svoboda from the Prague Noir anthology of Czech crime fiction (Paseka, 2016).

[ ]

Pavel Mandys (b. 1972) is Literary and film publicist. He graduated from the Faculty of Social Sciences at Charles University in Prague (journalism and mass communications). Mandys is an editor of the literary magazine iLiteratura.cz and the Prague Noir anthology.