Post-1989 changes

The November 1989 revolution was a turning point for all Czechoslovaks, with a profound effect on the form and reception of literature. Branches of Czech literature that had hitherto been separate (domestic, i.e. officially published, as well as émigré and samizdat literature) were now reunited. In the first euphoric months and years of the new freedom, the market was flooded with five-figure prose print-runs, which could not have previously been published as their authors were “prohibited” at home.

The nineties and the noughties were marked by the quest to find ways to finance culture and literature under the new conditions. As time passed, the state grant and subsidy support system stabilized, as did to some extent the private sponsorship system.

In addition to the material aspects of the new literary output, the problem that a common enemy had been lost proved very quickly to be of fundamental importance throughout the period in question. Under Communism, literature in general and prose works reflecting the state of society in particular were associated with the need for political engagement, either in the direct service of the regime or against it. Hence, for the majority of people in Czech society, good literature, like other types of art, was meant to replace the missing political dialogue and protest, and expected to express the civil dissatisfaction suppressed by the authorities.

Intoxicated by their newly won freedom, including the restored freedom of the press, people seemed to neglect the political and social side of literature for quite some time. Their altered social situation and lifestyle, the unprecedented opportunities opening up for self-realization, as well as writers’ hesitation over which subjects might be of interest and worthwhile, resulted in a mass exodus of readers. Within several years literature came to be an affair that only concerned a narrow community of experts and enthusiasts.

The writers’ loss of their previous privileged position, supposedly as the “conscience of the nation”, as the importance of literature was backstaged, was not a particular concern of the majority population, whereas the writers themselves felt this very strongly and tried to hark back to their former social prestige. In this they were meant to be assisted by a professional organization: Obec spisovatelů – the Association of Writers, established 3rd November 1989, which enjoyed considerable prestige from the outset, but which disintegrated, particularly after 2000 (as a reaction to the dismal state of this organization, Asociace spisovatelů was established in 2014, primarily for the younger generation of authors).

New opportunities for prose

In the first few years after 1989 a number of names of well-known and quite new authorial styles and poetics appeared on the prose scene. A large amount of respected output comprised works that had been written earlier, but that only now could be freely brought out by publishers at home. A prominent position was held from the outset by the 1960s generation of authors, with such celebrated authors as Josef Škvorecký, Milan Kundera, Ivan Klíma, Ludvík Vaculík and others, who were carrying on from their previous poetics, but at the same time trying to adapt to the new times and conditions.

Ludvík Vaculík and Ivan Klíma at Josef Zeman’s in Bezejovice. Photograph © Josef Zeman

The initial chaos gradually subsided, as people came to grips with the past and reassessed their values. Over the next few years a more stable quality and genre stratification of prose output gradually emerged, as names that acted as tried and tested “literary brands” emerged from the endless masses of writers. Literary prose subsequently spread over a broad, relatively stable range, bounded on either side by two fields: on the one hand challenging, elite works utilizing experimental, self-reflecting and essayistic elements, while on the other hand literature on the fringes of popular entertainment published in relatively high print-runs in line with the principles of commercial dumping. Between these two fields there was an unclearly defined sphere of prose that later in the new millennium was termed the “literary mainstream”.

Authentic prose

One of the most prominent streams of new post-1989 work was the programme of authentic literature, based on confidence in authors who tried to describe their own lives as truthfully as possible, without any redundant literary embellishment, games or illusions, in an entirely subjective and open manner, often with a sharp social-critical sting. This type of literature was most frequently published by authors who had personally suffered Communist oppression and who wished to publish their own powerful personal testimony.

The most productive genres in this stream of post-1989 literature were diaries and memoirs. This boom was based on the fact that the market was now swamped by texts which had not previously been publishable, and which had originally been intended by their authors to be purely personal matters, i.e. satisfying the need to record life passing by in the oppressive grip of the Communist regime along with a need of sorts to pass on a personal testimony and an urgent moral message to future generations. The key works here included Paměti 1–3, Memoirs 1-3, 1992, 1994, by Václav Černý, Jan Zábrana’s diary entries in Celý život 1, 2, My Whole Life, 1992, Teorie spolehlivosti, Reliability Theory, 1994, by Ivan Diviš and other authors such as Jan Hanč, Josef Hiršal, Bohumila Grögerová and Sergej Machonin. The present day was also presented in a distinctive and personal manner by a postwar Czech literary “classic”, Bohumil Hrabal, in works reflecting his personal experience of the November revolution and the early 1990s (Listopadový uragán, November Hurricane, 1990; Dopisy Dubence, Letters to Dubenka, 1994).

Jan Zábrana ‘Celý život’ (My Whole Life)

After the mid-1990s this publication spree subsided and they subsequently just appeared to a normal extent as just one strand in the broad literary spectrum, their role having been taken over by the memoir-novel genre, i.e. a genre of reminiscences on the interface between fiction and non-fiction. One exceptional late discovery of a private diary, whose publication was quite an event in the context of the times, was that of Deník 1959–1974 (Diary 1959-1974, 2003) by director Pavel Juráček.

Postmodern inspiration

Another of the most significant streams of post-1989 output was prose work under the influence of postmodern playfulness, boisterousness and laxity.

One author who had already produced highly postmodern works in exile was Jan Křesadlo (for example, during the 1990s his novel Obětina came out at home, 1994). During the 1990s the mantle of “postmodern classic” was taken over by Jiří Kratochvil, who actually advocated a postmodern programme (Medvědí román, Bear Novel, 1991; Má lásko, postmoderno, Postmodernity, My Love, 1994, and many other works). His prose works made use of uncanny and supernatural elements contrasting with entirely realist descriptions, bizarre motifs and untraditional narrative methods placed in a “Magic Brno” setting. He was one of the few to carry on work of this kind in the new millennium, inspired by the literary trend at that time to reflect life in its most traumatic forms under the Communist regime in combination with the distinctive poetics of his work (e.g. Lehni, bestie, Lie Down, Beast, 2002).

The prose work of Michal Ajvaz abounds in fantasy motifs and exuberant stories. Motifs include labyrinths, mysterious scripts and languages, and unwonted symbolic objects or books that lead the protagonist into other worlds and stories, set in a space which always acquires a tinge of the mysterious and the fantastic in Ajvaz’s work, e.g. Prague in his novel Druhé město (The Other City, 1993) and later the European cities and the Mediterranean in his extensive novel Cesta na jih (Journey to the South, 2008).

Michal Ajvaz ‘Druhé město’ (The Other City)

A plot set in the magical space of Prague, particularly in Vinohrady, is also typical of Daniela Hodrová’s work, with essayistic, self-reflective and philosophical elements interspersed with an often fragmented storyline, with motifs and subjects such as a mystical initiation ceremony, conversations with deceased strangers and loved ones, blurred boundaries between the world of dreams, memories and reality (e.g. the Podobojí trilogy, 1991; Kukly: Živé obrazy, Hoods: Tableaux Vivants 1991; Théta, Theta, 1992; and more recently e.g. Vyvolávání, Developing, 2010).

The most prominent author casting postmodern doubts on previous events, but at the same time paradoxically respecting the traditional genre of the historical novel was indisputably Vladimír Macura with his tetralogy entitled Ten, který bude (He Who Will Be, 1999). In short stories about both famous and entirely fictitious National Revival characters, Macura’s erudition as a literary historian came to the fore, as did his playfulness and hoaxing, as themes both in his literature and his life.

Playfulness and experimentation, sarcasm, irony, bizarre motifs and topics and his tendency to lyricize language and deeper, darker views of reality and reflections of life were characteristics of other prominent authors during the 1990s who cannot be easily classified in terms of genre, e.g. Václav Kahuda (Houština, Undergrowth, 1999), while Petr Rákos (Korvína čili Kniha o havranech, Korvína or the Book of Ravens, 1993) also published playful, specifically attuned postmodern works and Marian Palla (Zápisky uklízečky Maud, Notes by Maud the Cleaner, 2000) was distinctive for his humour and wit.

The new millennium saw fewer works steeped in the spirit of postmodernism, playfulness, unbridled imagination and fantasy, even if these did continue in many and varied forms to find a special place for themselves in contemporary Czech literature (e.g. prose works by Ivan Matoušek, Patrik Ouředník, Martin Komárek and others).

Prose works aspiring to be social novels

Authentic and postmodern elements can also be found in a broad range of prose that can be characterized as social, i.e. where the authors felt the need to express their experience and views of the overall transformation of the country, reflecting the newly crystallizing society and the political and cultural conditions in the autobiographical journal or novel genre. Contemporary conditions also came to be a subject for the generation of writers who had formerly been active as dissidents, e.g. Ludvík Vaculík (Jak se dělá chlapec, How a Lad is Made, 1993), Eva Kantůrková (Památník, Monument, 1994), Pavel Kohout (Sněžím, I Snow, 1993) and Ivan Klíma (Čekání na tmu, čekání na světlo, Waiting for the Darkness, Waiting for the Light, 1993). Even in the new millennium they did not abandon their poetics or their need to comment on their own lives and the state of society (e.g. in Vaculík’s Loučení k panně, Farewell to the Virgin, 2002, which combines a narrative about a dying love affair with reflections on the social climate).

Pavel Kohout ‘Sněžím’ (I Snow)

Michal Viewegh maintained his own special position in Czech literature throughout this period. In 1992 he published an exceptional successful novel (both among the readers and the literary critics) entitled Báječná léta pod psa, Blissful Years of Lousy Living: this bitter-sweet story of childhood and growing up under normalization, which as the name itself suggests, is neither a cheerful nostalgic memory, nor a straightforward condemnation, but a depiction of the feelings of a large proportion of the population who had muddled through this difficult period one way or another. Viewegh then began to publish commercially successful prose works in quick succession, primarily on love affairs set in a poignantly portrayed contemporary middle class reality, thus becoming the most widely read Czech author. His critical view of the new society and the new phenomena of life in it, the hopes and the disappointments, was also typical of the generation of authors that included Petr Ulrych, Jan Jandourek and Bohuslav Vaněk-Úvalský, whether they viewed the world around them purely through critical, grotesque or satirical eyes.

A special place at the confluence of several streams and trends was taken by Miloš Urban, who developed both occult themes and postmodern playfulness in connection with a particular historical epoch, but at the same time with a strong social-critical charge. His stories are always associated with a specific place or architecture and their occult atmosphere, whether a rural landscape, a cathedral or an entire quarter of a town, and they are always permeated with mystery, and inexplicable and bizarre murders and rituals, as well as the threat of the irreplaceable loss and callous destruction of these places (Hastrman, 2001).

In the latter half of the 1990s authors were also coming to the fore who had chosen a more intimate tone to reflect the mental dispositions and moods of their protagonists, as well as the state of Czech society in their prose works. In this way Jan Balabán’s work presents people who have been afflicted by life, who are alone and unhappy, but still looking for hope in their everyday lives. The oppressive atmosphere and feeling of emptiness is also highlighted by the special backdrop of industrial Ostrava (e.g. in the story collections Možná že odcházíme, 2004 and the novel Zeptej se táty, 2010).

The archetype of the unanchored protagonist who is tired of life and who moves within the circle of his own failures and stereotypes can also be found in the work of Zdeněk Zapletal (Půlnoční pěšci, Midnight Pedestrians, 2000), and Emil Hakl (O rodičích a dětech, Parents and Children, 2002) from a younger generation or Jiří Hájíček (Dobrodruzi hlavního proudu, Mainstream Adventurers, 2002).

One of the most distinctive and hard-to-classify prose works from the entire post-revolutionary period was the novel Sestra (Sister, 1994) by Jáchym Topol. This work, which was considered to be one of the peak achievements of literature at that time entirely surpassed all other output with its experimental and untraditional perception of the world and language. Topol’s kaleidoscopic evocation of the post-1989 social transformation is quite different in its emotionality and elemental and spontaneous narrative style from the other output on that subject at the time.

After publishing a novel set in the present day entitled Anděl (Angel, 1995), presenting the author’s distinctive view of the Smíchov underworld, Topol made a great impression with his prose work Noční práce (Night Work, 2001): in what is at first the realistically portrayed world of two young brothers, their peers and their village community in 1968, he progressively sets out not only a tangle of banal, exciting and hopeless relationships, but also the traumas of history and disturbing, dark and mysterious events and places. In his next novel Kloktat dehet (Gargling Tar, 2005), a postmodern fantasy, Topol again played around with the reality of 1968, this time in a story that offered an alternative history of a post-1948 Czechoslovakia that does not accept the invasion in August 1968 and defends itself to the last breath against the Warsaw Pact tanks.

Captivated by private joys and sorrows

A big topic in the early 1990s was feminism, sometimes of the combatively aggressive kind as in the case of Carola Biedermannová and Eva Hauserová, while others managed to reflect women’s lives in a more effective manner, i.e. not just seeing them in simplified terms of male-female rivalry, and thus presenting a more profound and nuanced testimony. The most prominent women writers who reflected the issues surrounding women’s perceptions of the world included Alexandra Berková (Temná láska, Dark Love 2000) and Zuzana Brabcová: her prose work Rok perel (Year of Pearls, 2000) examines the life of a woman who makes room for her previously suppressed lesbian feelings and a relationship that destroys her and fulfils her at the same time. Tereza Boučková carried on from her samizdat work (Když milujete muže, When You Love a Man, 1995) with prose works characterized by the brief, lapidary notes made by a protagonist frustrated by the behaviour of men and the challenging upbringing of adopted Roma children. She returned to this subject in 2008 with her media-supported novel Rok kohouta (Year of the Rooster), the diary confession of a woman who has to admit to herself and those around her that her happy family project has not succeeded and to find a way out of her personal and creative crisis. Other prominent middle-aged women writers whose work on the subject of finding themselves made quite an impression included Svatava Antošová and then Věra Nosková.

The new millennium witnessed the arrival of a new generation of prose writers who quite rapidly gained prominent positions on the Czech literary scene. Petra Hůlová was a literary discovery and a regularly publishing prose writer. She primarily attracted attention with her debut Paměť mojí babičce, Memory to My Grandmother, (2002), a family saga set in the exotic backdrop of Mongolia. Typical of the author’s manuscript is the urgent, earthy narrative, the colloquial language, the subjects of generational conflicts the status of women in society, the search for identity and the anchorage of characters dogged by loneliness and disappointment.

Another prominent debutante was Petra Soukupová, whose prose works K moři, To the Sea, (2007) and Zmizet, To Disappear (2009) tell of the complex family relations, ancient guilts and traumas that still affect the lives of new generations. Natálie Kocábová presented her characteristic and eccentric style in her novel Monarcha absint, The Monarch Absinthe, (2003), whereas Jana Šrámková gave her gloomy story entitled Hruškadóttir (2008) a quieter, more lyrical tone.

Changes in the new millennium

In the first decade of the new millennium this debt-paying spree of publishing books that could not come out under Communism subsided, as did discussions and polemics over the need for authenticity in modern literary work, while the boom in purely postmodern experimental prose slowly dried up. Postmodern elements basically came to be an organic and unsurprising element of individual literary styles. The retreat from mesmeric, playfully unbridled stories seemed to open up the way for works focusing on specific times and places.

The transformation of a large part of fiction into commercial “goods” and the writers’ loss of their previous privileged position also led to further discussions on literature’s new social function, as well as to a quest for an attractive, topical subject for contemporary work. One starting point appeared to be the unatoned guilt and moral dilemmas surrounding “history at large”, which seemed to be still awaiting basic consideration in the social and artistic spheres.

The increasing distance in time since the fall of the Communist regimes together with the generational change have brought about a wave of what is known as ostalgy, i.e. a nostalgic yearning for the Communist era (frequently seen from just a child’s perspective), which was also projected into literary production. The most distinctive trend in prose at the beginning of the third millennium was the thematic return to the 1940s-1980s. Writers were drawn in particular to the traumatic postwar period, which could be used in their works as a backdrop for thrilling action and distinctive figures. A favourite subject was the injustices perpetrated during the liberation and the expulsion of the Germans, as well as the Communist persecutions during the 1950s. In contrast the normalization years were a more intimate, often tragicomic space for childhood and youth. The return of the grand narrative was a great success: a realistic, gripping, broadly based story, often in the form of a family saga.

In addition to the “escape into history”, the new work that increasingly emphasized the way the world was opening up also began to include works that dealt with the search for living opportunities beyond the borders, whether in a totally globalized “Euroworld” in which everybody was dealing with more or less the same problems in analogous environments, or in remote, exotic locations which have hitherto retained their original character and distinctiveness.

What was characteristic was the authorial participation of the younger generation, i.e. the one that went out into the world after the revolution in 1989 to gain knowledge, or even younger authors for whom it was quite normal to spend the first years of adulthood out seeking experience in the world, both for study and for working reasons.

Despite these new trends, prose works in traditional genres using tried and tested authorial poetics continued to appear. The outpouring of literature on private relations and women’s fortunes was strong, both at the level of “highbrow” literature and at the transition to popular genres. Social novels increasingly ranged round the social-historical level (i.e. an additional normalization period or older plot line was added to the contemporary family plot).

Around the end of the 2000s, as a reaction to repeated assertions that Czech literature was undergoing a crisis, a debate emerged over the need to create an “engaged” work that would successfully respond to current political and social events; this programmatic hypothesis of several literary critics and writers, particularly poets, indicated that this should primarily mean left-wing engagement. However, such claims on literature had a greater resonance in literary polemics than in specific artistic works. If we do not include tabloid-style prose (or scandal-mongering confessions and biographies) satirizing and criticizing contemporary circumstances and high politics, the closest who came to this with regard to their poetics and readership were quite a varied band of authors: Miloš Urban, Michal Viewegh and Emil Hakl (with his novel Skutečná událost, Real Event, 2013).

Emil Hakl ‘Skutečná událost’ (Real Event)

Opening up to the world

Prose works set in foreign climes do not make up a uniform trend: the exotic backdrop often plays various roles, e.g. it can serve as an attractive external setting, a way to gain knowledge of another culture or an element that points up postmodern storytelling and the like.

One of the first works of this kind, a literary sensation, was the novel Nebe pod Berlínem, Sky Beneath Berlin (2002) by Jaroslav Rudiš. A narrative that came out of a short-term attachment, stylized as a sudden escape to an unknown city with an attempt to burn bridges and to start life afresh elsewhere and in a different way, it is a sequence of stories centring around various characters from a German city, particularly those whose lives are bound to the U-Bahn, i.e. the Underground. Other novels by Jaroslav Rudiš are set in Germany or some other primarily Central or Western European space, and their protagonists are young people who are looking for themselves in a globalized world.

The exotic backdrops also stand out in Petra Hůlová’s work, particularly in her debut Paměť mojí babičce, Memory to my Grandmother (2002), which tells the story of several generations of Mongolian women in the traditional environment of a family living on the steppes and in the vacuous relations and backdrop of the big city.

Siberia came to be the setting for another novel by Petra Hůlová Stanice Tajga, Taiga Station (2008), and a two-part novel by Martin Ryšavý Cesty na Sibiř, Roads to Siberia (2008), whose autobiographical narrator spends several journeys to the east getting to know the inhabitants of the Siberian taiga and its cities with all their post-Soviet paradoxes, shamanic teachings, nomadic traditions, broad Russian soul and strong alcohol.

Petra Hůlová

The exotic environment of South America is at the centre of attention for Hispanist Markéta Pilátová, as that is where she set her novels Žluté oči vedou domů, Yellow Eyes Lead Home (2007) and Má nejmilejší kniha, My Most Beloved Book (2009), in which she compares the lives of the locals with their European forebears and the traumas of history that their contemporaries still have to deal with. In Hana Androniková’s novel Nebe nemá dno, Heaven Has No Bottom (2010) the South American jungle and North American prairie provide a backdrop for the chief protagonist to get to know herself and a way for her to heal her body.

A quite special role is played by foreign lands in the work of middle and older generation authors, for whom this space is associated with the personal and family trauma of forced emigration (e.g. Edgar Dutka, Lubomír Martínek and Ivan Landsmann).

The past from the present viewpoint

Historical novels came out as a special genre throughout this period and in their more popular forms (i.e. as detective stories or pulp romances) they were indeed much sought after by readers, as can be seen in the novels of Ludmila Vaňková and later Vlastimila Vondruška. Earlier ages did not appear too much as literary inspiration in respected work (except in the unique prose of Miloš Urban), however the 20th century was increasingly seen as relevant, i.e. the period was understood to be an interface between the past and the present. Although novels reflecting this stage in modern Czech history were still coming out during the 1990s (e.g. Zdeněk Šmíd’s Cejch, Brand in 1992, a story of changing relations between Czechs and Germans in the Sudetenland “from the beginnings to the present day”), they clearly enjoyed a boom just around the turn of the millennium.

Whereas authentic literary works in the forms that they came out in during the early 1990s only came out exceptionally in the new millennium, what were known as memoir-novels were now increasingly frequent. These were autobiographical memoirs dealing with the political upheavals and complicated changes experienced by the older generation of writers, enhanced by meditations and psychologizing and not above looser storytelling (e.g. Pavel Kohout: To byl můj život??, That Was My Life??, 2005; Ota Filip: Osmý čili nedokončený životopis, An Eighth or Incomplete Biography, 2007, and other works).

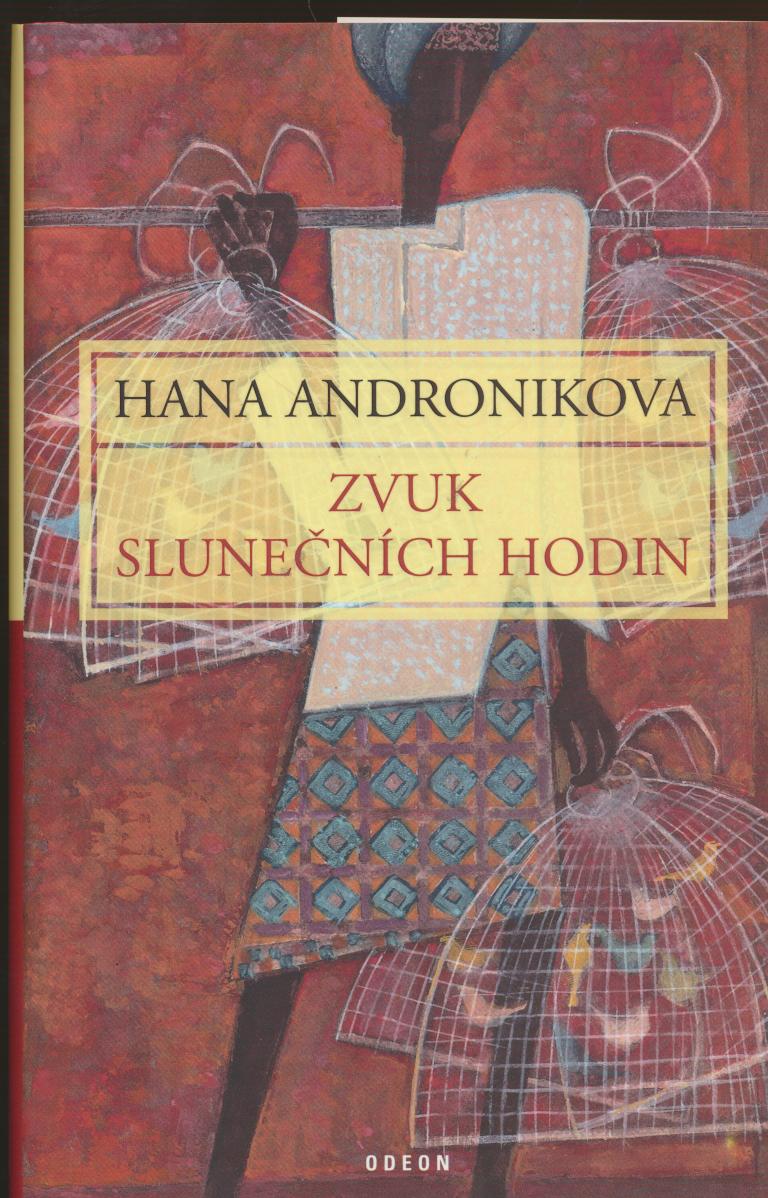

One of the most prominent trends involved works that drew on the traumas arising out of Czech-German relations, exacerbated during the war and the subsequent expulsions. Some of these focused on fateful epic tales of entire families and touched on such subjects as Jewishness and the Holocaust. In contrast to previous waves of prose on these subjects, the latest output was characterized by an emphasis on factographic work with sources and literature, which authors used as inspiration for their fiction narratives: it was not unusual for real individuals and their fortunes to be behind these stories and characters. Otherwise this kind of work avoided experimentation, going instead for traditional, realist narrative and a strong plot. That is how Hana Androniková conceived her novel Zvuk slunečních hodin, The Sound of the Sundial (2001), while Aaronův skok, Aaron’s Leap (2006), the tale of three generations of women affected by the Holocaust trauma, by Magdalena Platzová, is rather more intimate in mood. “Classics” such as Arnošt Lustig and Josef Škvorecký also returned to the Holocaust at this time; Květa Legátová, supposedly a debutante from the oldest generation, remained a solitary figure, who commanded attention not only with her novella Jozova Hanule Joza’s Hanule (2002), from the wartime period, but particularly with her short story collection Želary (2001), inspired by her hard life in Kopanice in Moravian Silesia, seemingly unaffected by time and evoking rural life back in the 1920s and 1930s.

Hana Andronikova ‘Zvuk slunečních hodin’ (The Sound of the Sundial)

Younger generation authors of both genders then began to see the Czech-German conflict in a much more focused light, and in contrast to the older interpretation of Czech history (offering an image of good Czechs and bad Germans) they mostly reflected the violence and lawlessness inflicted by the Czechs on the Germans. Hence a central topic came to be the postwar expulsion of the Germans. Hence an innocent German girl suffers throughout her life due to the principle of collective guilt in Kateřina Tučková’s novel Vyhnání Gerty Schnirch, The Expulsion of Gerta Schnirch (2009), while an old Jewish German woman tries to obtain an apology and reconciliation among unapproachable Czechs in Radka Denemarková’s novel Peníze od Hitlera, Money from Hitler (2006).

Precariously violent scenes were avoided by a series of smaller novellas that reflected the space abandoned by the Sudetens and characterized more by a lyrical tone expressing the feeling of solitude and irreplaceable loss in a place that will always have its secret. A Sudetenland perceived in this way can always be found in the work of Martin Fibiger, Jaroslav Rudiš, Martin Sichinger, Evita Naušová and others.

Another period that attracted the attention of quite a few prose writers was the 1950s, the events of which were often justifiably associated with, and organically stemmed from, the traumas of the 1940s. This tragic and lawless period offered strong stories, characters and moral dilemmas that also related to topical discussions nationwide, e.g. in the case of Jan Novák’s successful novel Zatím dobrý, So Far So Good (2004) about the Mašín brothers‘ resistance activities.

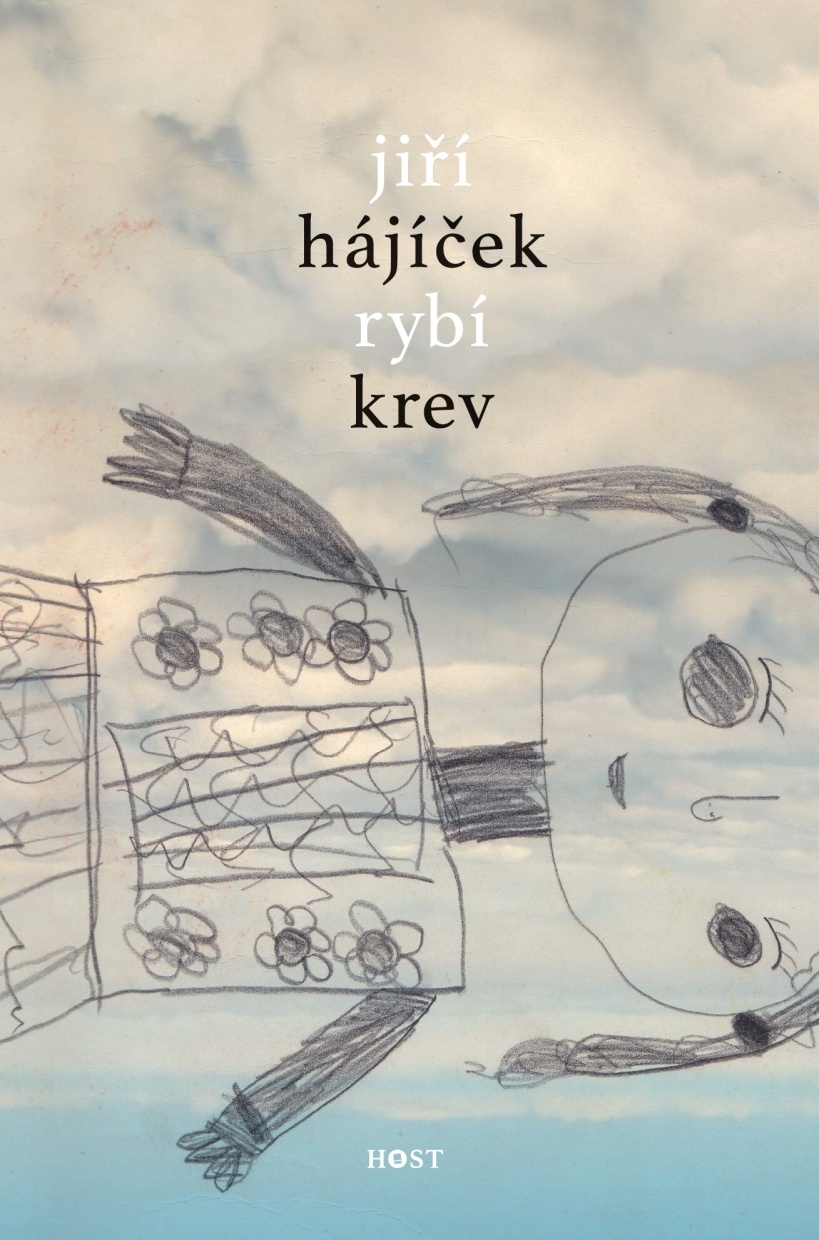

Novák’s next novel Děda, Grandfather (2007) was about another important subject from contemporary history, the forced collectivization of the countryside. There follows a series of boyhood memories from the narrator as an adult man, whose family experienced repeated ups and downs but who never gave up entirely to the ruling powers. The subject of collectivization was also dealt with in a detective story that delved into forebears’ ancient guilt by Jiří Hájíček in his novel Selský baroko, Rustic Baroque (2005). The closer his chief protagonist gets to specific historical sources and testimonies, the clearer it is that a judgment on an ancient dispute and a just, unbiased verdict is just not going to happen today.

Ancient family guilt and the burdens that affect the protagonists to this day and continue to distort relations between them are the subject of a novel by Tomáš Zmeškal, Milostný dopis klínovým písmem, Love Letter in Cuneiform (2008), as well as an extensive family saga by Pavel Brycz Patriarchátu dávno zašlá sláva, Patriarchate of Long Fade Glory (2003). The fortunes of a family started by a descendent of a unique Ukrainian patriarch after the First World War in the Sudetenland represents the fate of Czechoslovakia as a whole for several generations, as well as the breakdown of the traditional male role in the (post)modern world.

Authors born in the 1940s often adopt a child’s vision of reality (while acknowledging their autobiographical inspiration) in their work, which is thus full of tragicomic almost slapstick experiences and figures from an otherwise traumatic time, thus disrupting the otherwise traditional black and white perception of reality at that time. A distinctive head of a family, a tailor, who cures Stalin himself appears in Pecháček’s Osvobozené kino Mír, Liberated Peace Cinema (2002), while bitter-sweet memories and reflections can be found in a work by Antonín Bajaja Na krásné modré Dřevnici, On the Beautiful, Blue Dřevnice (2009), and the narrative of a young boy who has to live in a children’s home after his mother is imprisoned, is both tough and brittle (Edgar Dutka: U útulku 5, At Home 5, 2003).

Normalization grey

A child’s view of the world has been typical of another productive trend in recent Czech prose, namely works that reflect life under normalization. One of the first and most prominent works (which has also entered public awareness thanks to its successful theatrical production) was Hrdý Budžes, Mr B. Proudew, by Irena Dousková (1998). This naively honest view of little Helenka’s takes the reader into her unique world, which comically distorts the cheerless normalized reality while critically revealing it. This prose work is continued in the novel Oněgin byl Rusák, Onegin was a Rusky (2006), which is now the “traditional” narrative of Helena the student, who sees the reality around her with the critical and uncompromising vision of somebody forced to grow up in unfree conditions. A critical view of the small town society in which she lived and of her own family during the sixties and the seventies also gave rise to a trilogy of novels by Věra Nosková Bereme, co je, We Take What Is (2006), Obsazeno, Occupied (2007) and Víme svý, We Know Our Own Know (2008).

A disillusioned view of the inescapable world of normalization can also be seen in a work by Jan Balabán (Kudy šel anděl, Where the Angel Went, 2003) and the novel Stopy za obzor, Footprints Leading Beyond the Horizon (2006) by Pavel Kolmačka, in which the search for and attainment of Christian faith is prominently visible. A cheerless normalization adolescence marred by the threat that her native region would be destroyed by the construction of a dam is described by the protagonist of an extensive prose work by Jiří Hájíček Rybí krev, Fish Blood (2012).

Jiří Hájíček ‘Rybí krev’ (Fish Blood)

A frequently used compositional approach in these and other prose works is a narrative based on two time levels: a normalization childhood and post-1989 adulthood. The protagonist might well be living in freedom, when the frontiers and prohibitions that he had to deal with previously are now coming to an end, but not even this time of new opportunities brings him happiness or peace of mind: the protagonists in these works have been irreversibly affected by normalization, so the living conditions, personality adjustment and experienced traumas have an influence on their fortunes in subsequent stages of their lives.

On the other hand a warmer narrative tone regarding family troubles in difficult times, when bright moments and flashes of simple human happiness can always be found, is typical of Martin Fahrner’s work. Steiner aneb Co jsme dělali, Steiner or What We Did (2002) is the story of an ordinary family before and after 1989, in which even apparently lost souls tirelessly fight for a fully experienced life, family and happiness (it is not by chance that the story is permeated by the motif of football as a symbol of fighting spirit and indomitability).

An alternative to fixed standpoints on normalization and post-1989 times was provided by Petra Hůlová in Strážci občanského dobra, Guardians of the Civic Good (2010), teetering on the interface between the social novel, satire and hoax-like games. The narrator is a somewhat eccentric and backward young lady growing up in a fictional experimental Krakow combining the reality of normalization lifestyle in Czechoslovakia and an image of the entirely exhausted and impoverished totalitarian system of a developing state.

A quite different digression is the collection of short stories by Milan Kozelka Život na Kdysissippi, Life on the Missedissippi (2008), which presents the untraditional “saints” and “classics” of the pre-1989 underground.

Milan Kozelka

Post-1989 output set off in various directions and has so far outlived quite a few doubts and critical predictions. In spite of everything a number of distinctive literary works have remained in the public awareness over the last twenty years, surviving the times that gave them birth and enriching Czech literature as a whole. However, the literature of the new millennium keeps moving on, and only greater hindsight will show which of these movements and trends are still viable and productive in years to come. In current literary output we can so far only note a significant new phenomenon, namely prose inspired by real life stories, presenting biographical tales that are often on the borderline between literary and non-fiction prose (e.g. Jan Němec: Dějiny světla, A History of Light, 2013; Irena Dousková: Medvědí tanec, Bear Dance, 2014; Martin Reiner: Básník, Poet, 2014), but future years will show whether this output will result in more prominent works.

Translated by Graeme Dibble

[ ]

Alena Fialová (1976) works in the Institute of Czech Literature AS CR, where she focuses on post-war Czech prose and contemporary literature. She is the author of Poučeni z krizového vývoje. Poválečná česká společnost v reflexi normalizační prózy (Academia 2014) and is the main editor and co-author of the publication V souřadnicích mnohosti. Česká literatura první dekády jednadvacátého století v souvislostech a interpretacích (Academia 2014).