The Czech Literary Centre asked four experts from four European countries to write an overview of trends in literature for children and young adults in their country. In November we published texts on the situation in Germany and France (check them out HERE) and in December we continue with texts from Britain and Spain.

3. Great Britain

What’s new on the British “kid lit” scene

When looking for trends in the world of literature for children and young adults in Britain, one has to keep in mind the obvious: English is an omnipresent lingua franca spoken both as a first and second language, and English-language books for children are part of a vast industry that caters for the educational and leisure needs of a global population of readers.

The other aspect worth stressing is that books for young readers are part of an infrastructure that includes not only publishing, bookselling and the libraries network, but also an array of institutions, organisations and associations that promote literacy and reading, provide “discoverability” tools and produce educational resources. Apart from the UK chapter of the well-known international YBBY network, there are reading promotion charities, such as The Book Trust, The Reading Agency or the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education, working alongside children’s librarians and teachers.

Recalibrating representation and inclusivity

One of the most significant recent trends is a continuous process towards “localisation” to ensure that English-language books reflect the world of their readers. If reading is to shape consciousness and help develop a sense of identity, children should be able to relate to the stories they read and identify with the characters. Yet, for too long, children’s books had been out of step with the diversity of British society. Reflecting Realities, a study commissioned by the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (CLPE), showed a significant need for better ethnic representation in children’s literature: only 1% of the 9115 children’s books published in the UK in 2017 had an ethnic minority protagonist, and only 4% featured any ethnic minority characters at all, while, as reported by the Education Department, 32% of school children in England are from minority background. The findings prompted the launch of a number of initiatives aimed at redressing this imbalance and led to the creation of recommended reading lists by websites such as Love Reading4Kids highlighting books with protagonists from ethnic background.

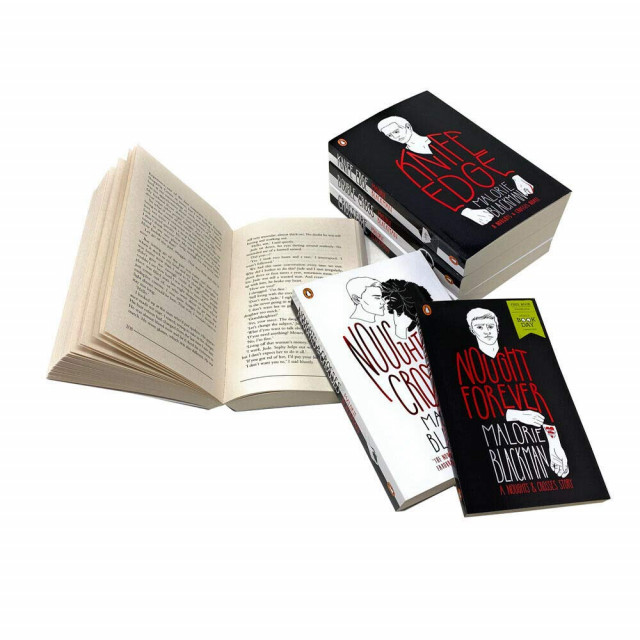

Given the ongoing emphasis on the need to validate ethnic minority children’s reality and experience, the second survey conducted in 2018 and published the following year showed a welcome change to 4% of books featuring a minority protagonist. The same year saw the production of Noughts and Crosses, a television series based on the bestselling young adult novels by Malorie Blackman, Britain’s only children’s laureate of colour. The novels, the first of which was originally published back in 2001, were written in the genre of speculative fiction and presented an alternative future where race roles are reversed in a world where Africans had colonised Europe and subjugated the white population. This literary device makes young readers reflect on colonial history and the legacy of slavery reflected in societal inequality, a topic brought into focus by the Black Lives Matter campaign. The successful TV series was first aired in March 2020 with a sequel already announced.

“In Other Words” stands for Translation

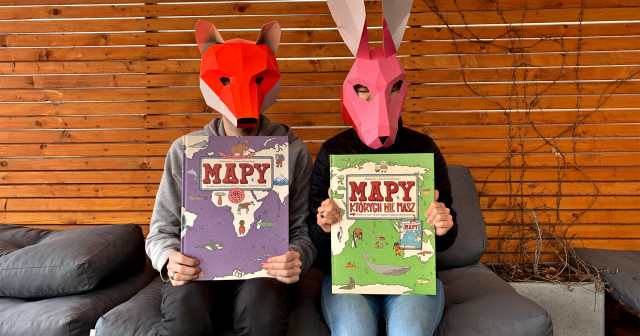

Children’s books in translation is another trend worth mentioning in the context of growing diversity in “kid lit” publishing. Translated literature forms a very small share of newly published books, but the number of books in translation has been steadily rising in the past decade and have even been reported by Nielsen Book in 2019 to sell better than original writing. While this refers mostly to literary fiction for adults, there have been some translated books for young readers in the top selling category. Maps, the lavishly illustrated reference book for young readers by the Polish couple team Aleksandra Mizielińska and Daniel Mizieliński, is a case in point: the book became a surprise bestseller after it was published in 2013.

But most books in translation require a concentrated effort to materialise: the original has to be discovered and the translation and production often supported with a subsidy. This was demonstrated by In Other Words, a two-year programme by The Book Trust that aimed to raise the profile of translated books for young readers and to encourage UK publishers to publish more such titles. A shortlist, selected from around 200 submissions of original titles, was presented to British publishers with the incentive of a marketing subsidy and a toolkit with a range of resources.

A new old category: World Kid Lit

An ongoing campaign that champions diversity in children’s books is World Kid Lit, a blog run by a collective of volunteers. While “kid lit” is the trendy new label for children’s books, “world literature” is a term dating back to a time long before books for children and young adults were classified as a separate category. The blog coined a combination of the two and embarked on promotion of diversity in children’s literature with articles, interviews and reviews, as well as recommendations of titles for translation. Set up in 2016 with the idea of designating September as World Kid Lit Month, it now has a worldwide following among authors, translators, librarians and teachers, as well as publishers. It also lists books published in English translation, showing a year on year growth. And this is where the role of independent presses needs to be mentioned: the majority of books in translation, whether aimed at young readers or adults, are published by independents with dedicated imprints: Oneworld with Rock the Boat, Pushkin with Pushkin Children’s or The Emma Press, while Tiny Owl, Lantana and Book Island are children’s publishers committed to responding to the multicultural nature of British society. There are also recent newcomers, such as Centrala, a publisher specialising in graphic novels and comics, based in two locations in central Europe and in London.

Poetry for young readers

Trends in children’s literature often echo overall trends – after all, the boundary between age-defined reader categories can be blurred. In recent years, growing interest in poetry has been documented in sales and engagement with live poetry events and competitions, and the same trend has been observed in poetry for children. A 2018 survey by the National Literacy Trust found that “nearly half of children and young people engage with poetry in their free time, reading it, listening to it, writing it and performing it”, and there is a plethora of resources produced by the Poetry Society and other organisations to encourage even more such engagement. Numerous recommendation lists highlight themed poetry anthologies – focused on animals or nature – as well as titles by single authors, including children’s poetry classic Road Dahl or veterans Julia Donaldson, Brian Patten and Michael Rosen.

But there are two books by young authors that stand out among the many recent publications, both employing poetic narrative to tackle tough topics: Dean Atta’s Black Flamingo (2019) weaves themes of race, gender, identity and coming of age into a beautifully crafted novel in verse about a mixed-race teenager who finds himself as a drag artist and eventually embraces his uniqueness. In the second book, The Girl Who Became a Tree (2020), the award-winning performance poet Joseph Coelho, who is immensely popular with children, turns from his trademark funny word play to a different tone in this delicate novel in poems, based on the myth of the nymph Daphne, about a young girl who loses her father.

– Alexandra Büchler

4. Spain

The panorama of Spanish literature for children and young adults

Details on sales of books for children and young adults in Spain for 2018 presented by various institutions1See the Spanish Book Market Report 2018. underscores the fact that this branch of the book market is blossoming and grows every year. Books for children and young adults earned 6% more than in the previous year and amounted to 14% of the output intended for export. This is logical in a country where 38% of the population admit to not reading a single book in a year and where total sales of books for children and young adults equals 12.8% of all the books sold. Data from the Ministry of Education and Culture2An overview of Spanish books published in 2018: sector analysis: https://sede.educacion.gob.es/publiventa/panoramica-de-la-edicion-espanola-de-libros-2018-analisis-sectorial-del-libro/estadisticas-libros-y-lectura/21661C has provided us with more information on what is going on.

Given the current fragmentation of the book market, the sector of books for children and young adults is one of the most active. I counted almost 100 independent publishers publishing children’s books in my own personal list. Some release five or six new titles each year, others more than 12. The large publishers from this sector publish textbooks, and their literary divisions are primarily aimed at schools. Mónica Rodríguez, Gonzalo Moure, Begoña Oro or Alfredo Gómez Cerdá are some of the authors that are repeatedly encountered in this group. These types of books usually deal with worthwhile and current social themes.

In 2017, 11,296 titles applied for an ISBN, though not all were published. This means 30 new titles on average per day. Given these numbers and despite the fact that applications were 29.3% lower in 2018, it remains an amount that is difficult to accommodate in terms of both economics and research. In the commercial system based on the large turnover of books, first runs rarely reach 2,000 books, and many of the smaller editions don’t even reach a print run of 500 copies, a quantity that the market is able to absorb. In this situation, it often happens that writers and illustrators publish many titles annually with the hope that their book will sell out. 99% of ISBNs requested in 2018 were for first editions. If we take into account that the average price of a children’s book is 10 euros, it is not necessary to do elaborate calculations to see that writers and illustrators barely make a living from the sale of their work.

One of the most striking tendencies in recent years was the large-scale production of picture and illustrated books. Publishers such as Siruela, Impedimenta or Nórdica have joined the ranks of traditional publishers of children’s books. The topics are varied: from educational through purely imaginative, where the illustrators show off their art, to even those focused on self-help such as the bestseller El monstruo de colores (The Colourful Monster, 2018) by Anna Llenas. This title has sold more than 500,000 copies and paved the way for similar books from other publishers. Everything that a parent or teacher who wants to use books to teach children, whether it is how to brush their teeth, become toilet trained, manage emotions, or warn of an environmental catastrophe, is available. I wrote about this phenomenon on my blog.3https://anatarambana.blogspot.com/2017/08/superlij-llega-la-literatura-infantil.html

Another interesting tendency was books for first time readers: i.e. small-sized fold-out books with rhymes about everyday topics. With regards to the usual themes, many books tend to be more sociological than literary: migration, ecological catastrophe and women’s issues. These books try to accommodate current social discussion and welcome the support of parents and teachers, the very people who buy these books.

The rise of nonfiction books deserves special attention. All publishers include in their range titles that attempt to increase factual knowledge. However, Zahorí Books is the only one that is exclusively dedicated to this field. Right now, a boom in books on nature is underway.

This development in picture books, it seems, pushed reading to the background for children from 8 to 12 years old. Book production was smaller and focused on issues connected with lessons or preserving classics. Therefore, the success of Los futbolísimos (The Footballest, 2018) by Roberto Santiago, which has sold more than two million copies over its 16 titles, is no surprise.

In recent years, comics and graphic novels have undergone an impressive rise, though 75% of the 4,000 titles released in 2019 were translations.4https://www.lavanguardia.com/vida/20200713/482289805817/el-75-de-los-comics-que-se-leen-en-espana-son-producciones-extranjeras.html The publisher Salamandra has widened knowledge of its name thanks to the Fnac Award (an international award for graphic novels Fnac-Salamandra Graphic, ed.) and operates side by side with other traditional publishers, such as Astiberri, Dibbuks and Norma among others. Among teachers and parents, this is an overlooked phenomenon, while at the same time, perhaps the most interesting works can be found there. One example is Artur Laperla and his series Superpatata (Super Potato, 2011), which has sold more than 40,000 copies, in which readers discover adventure as well as humour and lively dialogue.

– Ana Garralón

[ ]

Alexandra Büchler is director of the European platform Literature Across Frontiers, editor and translator of prose, poetry and non-fiction between her native Czech and English, with thirty publications to her name. She has edited six anthologies of short fiction in translation and was series editor of Arc Publications’ bilingual poetry anthologies New Voices from Europe and Beyond 2006-2016.

Ana Garralón is a Spanish pedagogue, translator and literary critique specialising primarily in children’s and young adult books. She published the book Historia portátil de la literatura infantil (Portable History of Children’s Literature, 2001) and Leer y saber. Los libros informativos para niños (Read and Know: Informational books for children, 2013). She gives lectures and runs educational workshops in Spain and Latin America. She primarily focuses on books for the youngest readers. She writes her topical reflections on her blog about children’s books called Anatarambana, which was awarded the 2016 Spanish National Award for the Promotion of Reading (Premio Nacional de Fomento a la Lectura 2016).

| 1. | ↑ | See the Spanish Book Market Report 2018. |

| 2. | ↑ | An overview of Spanish books published in 2018: sector analysis: https://sede.educacion.gob.es/publiventa/panoramica-de-la-edicion-espanola-de-libros-2018-analisis-sectorial-del-libro/estadisticas-libros-y-lectura/21661C |

| 3. | ↑ | https://anatarambana.blogspot.com/2017/08/superlij-llega-la-literatura-infantil.html |

| 4. | ↑ | https://www.lavanguardia.com/vida/20200713/482289805817/el-75-de-los-comics-que-se-leen-en-espana-son-producciones-extranjeras.html |