Like every good story with a happy ending, this one about the resurrection, rebirth or reawakening of Czech comics after 2000 keeps coming back in various forms to be retold over and over again to new generations of enthralled listeners. Over the years it has been reiterated and refined by dozens of short and more in-depth articles, interviews, features, studies and dissertations, and as a result it has become an almost universally accepted part of the discourse about the history of the pictorial narrative form in this country. There is certainly no controversy surrounding the basic argument: even a cursory comparison of the statistics for comics published (and at least in some way responded to, read and reflected on) in the year 2000 and a decade later clearly shows an increase in the number of works published, while any regular consumer of Czech media – audio-visual as well as print – must surely have noticed that they have been hearing and reading more about “cartoons” recently than in the past. Nor is there any real doubt concerning the progress made in qualitative terms, which means that those enthusiastic declarations of a “golden age of Czech comics” are ultimately borne out in many respects.

At the same time, however, this narrative about the gradual rise of the “ninth” art in panels and speech bubbles at the start of the 21st century needs to be qualified further. An almost obligatory part of these glad tidings about the coming of the new comics is the postscript that the work of the artists who emerged post-2000 and were initially concentrated around subcultural publication platforms in the form of magazines (Aargh!, Pot, Zkrat) or websites (especially Comx.cz and Komiks.cz) was targeted more at adult readers and that through them homegrown comics “were freed from the bond to child readers” – or, put simply, “grew up”. For too long, this discipline – long marginalized and during its darkest days actively rooted out – had to bear the injustice of remarks about childishness, naivety and simplicity, so it is easy to understand the readiness of early 21st century Czech comics to distance themselves from their traditional child readership – at least in some of their public declarations. A role was also played by the growth in translated comics for adults at the turn of the millennium, which occurred virtually in parallel in both more traditional, mainstream commercial output (as in the magazine Crew) and the more alternative sphere (e.g. in the output of Mot publishers). Therefore, after the long twentieth century, when Czech comics for children and young adults clearly dominated the local market for this medium (and the public image of it), they found themselves facing an unforeseen crisis of identity and self-determination in the early years of the twenty-first century.

Of course, the stagnation of children’s comics and their difficulty gaining ground between 2000 and 2009 cannot be attributed solely to new artists and creators turning to adult readers, and various other factors may have had an even greater influence. The market for homegrown children’s magazines had still not recovered from the crisis of the mid-1990s and was struggling to find a meaningful space to operate in under the new conditions. This was symbolically affirmed in 2001 by the closure of the magazine Ohníček (Little Fire), which over the fifty years of its existence had been home to many of the best Czech comic strips for children and young adults, from Pavouk Nephila (Nephila the Spider) and Professor Dugan to Mořští vlci (Sea-Dogs), Barbánek the dog and more. Therefore, comics aimed at younger readers, traditionally developed in the form of regular series consisting of one- or two-page instalments, lost a large proportion of their publishing platforms during the 1990s, and those which survived often saved money by buying in cheaper work from abroad or restricting the comics content as a whole.

Therefore, while for homegrown “comics for adults” the early years of the third millennium represent a period when projects emerging from the subculture, initially of a purely fanzine type, presented young and aspiring artists with new publishing opportunities (to print short, one-off pieces of work), and when the focus of lengthier work began to shift from serializations to book collections (by 2005 the trilogies-to-be Alois Nebel, Oskar Ed and Monstrkabaret Freda Brunolda [Fred Brunhold’s Monster Cabaret] were already underway), original Czech comics for children and young adults found themselves in decline and struggling to survive between 2001 and 2010.

Čtyřlístek 2000–2009: at least holding its ground

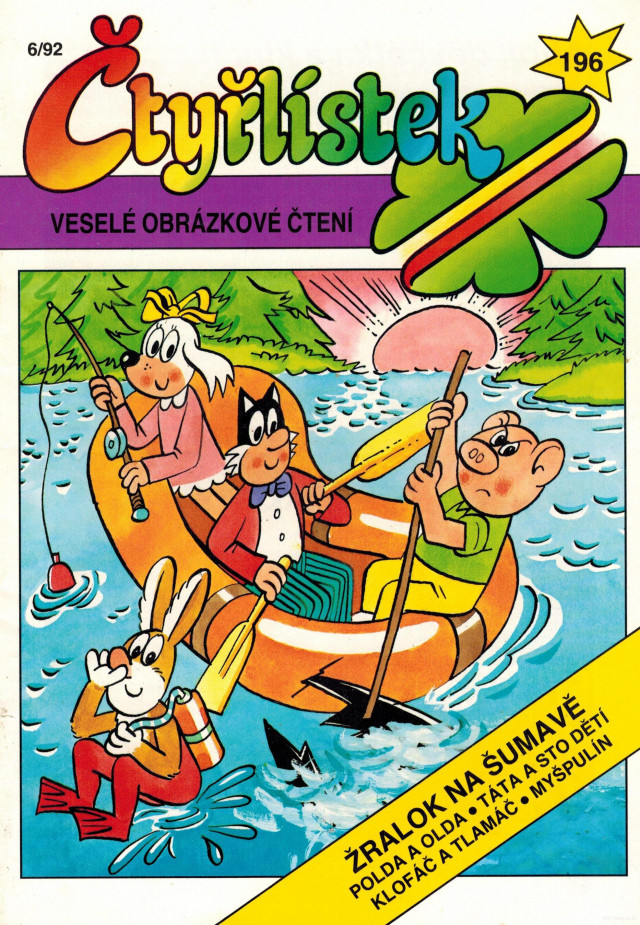

In the first decade of the new century, the most important platform for Czech magazine-based cartoons for children and young adults – and not only in terms of the total number of pages dedicated to comics – was still Čtyřlístek (Four-leaf Clover). Established in 1969, this magazine had more or less consolidated its position by the period in question. After a difficult start to the 1990s, when fierce competition seemed to spring up overnight in the form of translated series like Mickey Mouse and Bugs Bunny, by the end of the millennium it had managed to stake out a new space to operate in, albeit a more constricted one than before, as the only original Czech entirely comics-based periodical, benefitting from an uninterrupted publishing history, tradition and perhaps also feelings of nostalgia. Nevertheless, this move away from its former monopolistic position necessitated various changes and concessions; presumably in an attempt to make production more efficient, there was a greater reliance on digital technology (for colouring and typesetting), though the results generated by this use of computers, initially at least, did not achieve the same level of quality as in the previous era. Perhaps it was the attempt to decrease production costs or perhaps the desire to simplify editorial work by preparing a larger proportion of material in-house which led to less space being offered to other artists by Čtyřlístek. The inclusion of the regular series Rexík (like the magazine’s title series, this was also drawn by Jaroslav Němeček) reduced the number of series “slots” in each issue available to other creators.

At the same time, Čtyřlístek lost some of its long-term collaborators in the early years of the third millennium. The former hegemony of Ljuba Štíplová in scripting the title series was long gone. Her skilful and imaginative stories about the four animal friends became increasingly rare and Čtyřlístek (the series) began to focus on more epic, dramatic stories full of frantic twists and turns. Věra Faltová, a long-time contributor to the magazine, bowed out with her last pieces of work, which already lacked the self-assurance of the earlier comics; and after ten years perhaps the best “supporting” Čtyřlístek series of the post-revolution era came to an end: the tales of two mice Anča a Pepík (Annie and Joey) by Lucie Lomová. It was very difficult for the magazine to find worthy replacements, and despite introducing several new long-running series – such as Čaroděj Metloděj (Metloděj the Magician) by Zdenka Študlarová and Příběhy z lesa (Tales from the Forest) by Marie Satrapová – and trying to update the look and diversify the genres of the cycles it ran – for example, with the short-lived stories Vesmírní poutníci (Space Pilgrims) by J. Bourek and Jozef Fraško – with the one possible exception described below, none of the Čtyřlístek series introduced in the decade in question were particularly well received by readers.

That unique publishing “success” in the category of supporting Čtyřlístek series was the cycle about the space-travelling schoolgirl Viktorka and her two friends/colleagues, Žabža and Fláj. The series by the scripter Klára Smolíková (*1974) and the cartoonist Jan Smolík (*1965), which was published between 2004 and 2010 (and briefly revived in 2013–2014), was a hit with readers thanks to the imaginative stories and the functional, dynamic artwork with its distinctive use of colour. The episodes, based on a “lite” version of science fiction, were not afraid to give a nod to stereotypes of the genre, but at the same time, despite the strictly episodic nature of the series (according to Čtyřlístek’s guidelines, each six-page instalment had to offer a complete, self-contained story), they managed to come up with new ideas without descending into stereotypes.

Magazines for children and young adults 2000–2009: flirting with translations

In its carefully delimited way, normally confined to one or two pages, the serialized comic strip continued to have its place in traditional homegrown magazines for children and young adults. So in the first decade of the 21st century comics did appear in Sluníčko (Little Sun), Mateřídouška (Thyme) and ABC (for older readers); however, apart from the few exceptions mentioned below, these tended to be lower-quality, sometimes quite amateurish pieces of work, and although they made it into print they hardly resonated with the readership at all: in some years it seemed as though editors were willing to publish almost anything that came their way. There were further efforts to cut costs and supposedly increase efficiency by including stories bought in from elsewhere: for example, ABC made a rather clumsy attempt to tap into the American superhero mainstream (by running Batman stories broken up into short segments), while Mateřídouška played host to the sarcastic little boy Titeuf and the young witch Meluzína (originally Mélusine). In those days it was also not unheard of to recycle older series in the form of reprints or attempt a less than successful comics “remake”: for example, a comeback by Barbánek with the participation of both the original creators, Jiří Havel and Věra Faltová. Unfortunately, the quality of these new stories, published in Sluníčko from 2004 to 2009, fell far short of the original miniatures in Ohníček from the 1970s and 80s. There was a similarly awkward ending to the long-standing collaboration between Jaroslav Malák and Mateřídouška: the cartoonist behind Tři prasátka (The Three Little Piggies) and Klok a Kloček (Big Roo and Little Roo) bowed out from the magazine in 2001 with the tales of the two eponymous kittens from the series Žů + Žo, which were a mere shadow of the earlier playful comic strips that had developed the traditional area of “an animal version of everyday life”.

Looking back a decade on, very little of enduring appeal seems to have come out of the magazine comic strips of the “noughties”. Although not always a favourite with the critics, from the turn of the millennium high quality was generally guaranteed by the copious work of the aforementioned duo of Klára Smolíková and Jan Smolík: whether it was the stories of anthropomorphised animal friends for very young readers Medvídek Lup a jeho kamarádi (Lup the Bear and his Friends) or the tales of a baron’s children in a fairytale medieval setting Na hradě Bradě (The Castle of Chin; both these cycles came out in Sluníčko), the work always skilfully combined a functional, light-hearted style with an imaginative, non-repetitive narrative structure. Tomáš Chlud (*1976) also produced original work that was head and shoulders above the low standard of the period. As well as a variation on the popular fantasy genre (Velké putování [The Great Voyage], carried by Mateřídouška), he also demonstrated his ability to construct entertaining everyday miniatures out of the life of two siblings, Kája a Filip (Cara and Phil, which came out in one of the period’s attempts at a “new children’s magazine”, Země pohádek [The Land of Fairy Tales] ). Another series noteworthy for its quality of workmanship and deviation from the usual genres is Berta kontra Modrovous (Berta against Bluebeard), which was created for Mateřídouška in 2004 by “Kipko” and “Shooty” [Martin Šútovec, *1973]; otherwise, however, the magazine output of the period did little more than meet the basic consumer demands of the day. From ABC – i.e. a magazine which in previous decades had given Czech comics dozens of legendary series – perhaps the only series worth mentioning is one that was very unusual for the magazine and took the form of a regular cartoon strip about a tomcat, Mourrison, which has been produced by Lukáš Fibrich without interruption since 2002 (*1974).

Comics published in book form 2000–2009: re-issues and a few one-offs

The unflattering state of Czech comics for children and young adults printed in magazines was obviously mirrored in the near-moribund book output. Only a small number of homegrown comic-book volumes with stories for very young to young readers were published between 2000 and 2009, and the only contemporary series to be brought out as collections or anthologies in that period were Čtyřlístek (repeatedly), Rexík (2000 and 2006), Malý Vlk a Bystré Očko (Little Wolf and Sharp Eye, one of the last series for Čtyřlístek by the aforementioned Věra Faltová, 2006), Medvídek Lup a jeho kamarádi (2008), Mourrison (2006) and Kája a Filip (2008). In the following decade another two or three cycles from that time were brought back, but otherwise Czech magazine-based comics from the start of the third millennium were practically dead and buried. On the other hand, there were many more collected re-issues of older Czech comics for children and young adults: 2001 saw the very successful publication of the first Velká kniha komiksů (Big Book of Comics), reprinting serials from the celebrated era of the magazine ABC, and a year later the volume Čtyřlístek: Prvních dvanáct příběhů (Four-leaf Clover: The First Twelve Stories) launched an ambitious plan to gradually make all of the stories about the popular funny animal quartet available in large hardback books (in chronological order by date of original publication). There were also separate books reviving a number of older children’s comics from the 20th century and introducing them to new readers: Kocour Vavřinec a jeho přátelé (Tomcat Lawrence and his Friends), Vynálezy pana Semtamťuka (The Inventions of Mr Tofrobang), Obrázky z českých dějin a pověstí (Pictures from Czech History and Legends), Anča a Pepík, Robot Miki, Ježek František (František the Hedgehog), Barbánek and others. It was as though this glorious history – and the attendant nostalgia – had triumphed over the drab present.

There was also a bare minimum of output purposely designed for publication in book format. If we leave aside the Čtyřlístek specials – which, in keeping with a tradition established at the end of the 1980s, offered a new collection of the four animal friends’ adventures each year – then from 2000 to 2009 not more than half a dozen original Czech comic books for children and young adults were published in total. The square-format book Šmankote (Jeez), drawn by the aforementioned Tomáš Chlud and scripted by Denisa Kirschnerová (*1974), brought to life in comics form the puppet characters Spejbl and Hurvínek, but the skilfully updated cartoon rendering of the traditional duo was let down by the uninspired and rather clumsily developed scenarios of the individual short stories. Lucie Lomová (*1964) took on an even more revered national classic, adapting five stories by Karel Jaromír Erben for the hardback volume Zlaté české pohádky (The Greatest Czech Fairy Tales), published in several languages in parallel. Pavel Čech’s (*1968) opulent large-format album Tajemství ostrova za prkennou ohradou (The Mystery of the Island Outside the Board Fence), which is a cross between an artist-illustrated book and a comic book and clearly owes a debt to the work of Jiří Trnka, was the first large-scale work in which the artist developed themes and motifs that were later to become emblematic of his work: a nostalgic recollection of childhood and children’s friendships, a love of adventure stories from years gone by, an atmospheric and poetically dreamy depiction of the magic of everyday adventures, and a penchant for mysterious spaces, both internal and external, that are hidden from view.

These three comics were the work of creators who, in one way or another, were active within the emerging comics subculture that formed in the first decade of the millennium around Aargh!, Pot and “Generace Nula” (“Generation Zero” – it acquired this self-defining label in 2007 with an exhibition of the same name). Naturally, the occasional large-scale comics project aimed (not always exclusively) at child readers was to come out of this loose network of young comics artists. The book Ticho Hrocha (The Silence of the Hippo, 2009) by the award-winning artist David Böhm (*1982) attracted a lot of attention, though more from outside comic-book circles. This adaptation of African folk tales, told through the medium of a child narrator writing an essay, was noteworthy for its unique artistic style and unusual subject matter, and in the year when its creator was nominated for the Jindřich Chalupecký Award (together with Jiří Franta), it offered Czech readers outside the art world an insight into unfamiliar and unexplored areas of alternative comic books for children and young adults.

The book Laddugandy (2008) by Darja Bogdanova Čančíková (*1982) also brought a distinctive form of artistic expression with unusual stories about fictional beings and their everyday joys and sorrows which were very different from the usual commercial fare for children. However, these subtle stories, likened to Tove Jansson’s Moomins in the publisher’s blurb, did not achieve widespread popularity. Finally, from the opposite end of the spectrum, it is worth mentioning an unsuccessful attempt to launch an original commercial series which Jan Jelen (script) and Petra Z. Jelenová (artwork) came up with in 2009. The volume Drak Drango: hrdina přichází (Drango the Dragon: Enter the Hero) deserves a mention for its approach to form, combining segments of prose with comic pages – something which was quite unusual at the time but was to catch on in subsequent years.

Of course, hybrid works of this type were not an invention of the first decade of the third millennium; even in the Czech context, they had already appeared, for example, in the aforementioned Ježek František. However, as a result of the phenomenal popularity of the translated series Diary of a Wimpy Kid by Jeff Kinney (*1971), which was also recounted in prose with comic-form insertions or segments, the coming decade was to witness a revitalization of this type of publication, and with it a general revitalization of Czech comic books and partly comic books for children and young adults. In drawing to a close, a final mention should go to Zeď (The Wall) by Petr Sís (*1949), the Czech translation of which was published in the same year as the English original (2007), as an important source of inspiration in the years to come. The interest contemporary comics for children and young adults have shown in national history and the stories of those who lived through it can probably be traced back to this book.

The fact that Petr Sís and Jeff Kinney have ended up side by side in the paragraph above may strike some people as sacrilegious, but in its own way it is testimony to the unprecedented breadth of today’s comics and comic-inspired works. In the early years of the 21st century this was not particularly apparent in the Czech setting due to the overall deceleration and marginalization of this type of output, but in the following decade, which will be examined in part two, this diversity and variability was to fully impact upon Czech comics for children and young adults.

[ ]

Pavel Kořínek works as a researcher at the Institute of Czech Literature CAS and is also a comics theorist, historian and journalist. From 2010 to 2012 he was the principal investigator for the Czech Science Foundation grant project Comics: History and Theory, whose main outputs were the two-volume Dějiny československého komiksu 20. století (A History of 20th Century Czechoslovak Comics, 2014), co-authored with Tomáš Prokůpek, Martin Foret and Michal Jareš, and the introductory monograph V panelech a bublinách: Kapitoly z teorie komiksu (In Panels and Speech Balloons: Chapters from the Theory of Comics, together with Martin Foret and Michal Jareš, 2015). In recent years he has edited lengthy books about the series Punťa (2018, with Lucie Kořínková) and Čtyřlístek (2019). He has worked as a curator and editor on the exhibition projects Signály z neznáma. Český komiks 1922–2012 (Signals from the Unknown. Czech Comics 1922–2012, Brno – Prague – Pardubice, 2012 and 2013), 100 Years of Czech Comics (Tokyo, 2017 and 2018) and Mezitím na jiném místě (Meanwhile, Elsewhere, 2018–2019, an exhibition organized by Czech Centres and presented in more than 30 venues). He is a founding member of the Centre for the Study of Comics. He has taught courses on the history and theory of Czech comics at Charles University and Masaryk University and reviews modern comics and translated prose for the fortnightly journal A2. He has also chaired the board of the Czech Academy of Comics since 2018.