The Magnesia Litera occupies a special position in the Czech Republic. Of all the many literary awards in existence, the Litera is the best known and most widely recognised among the general public. This award “makes” writers – it guarantees them star status and increased sales. In the case of the Litera, it is a serious enterprise which has tangible, positive effects. The awards are divided into nine categories, which aim to cover all domestic book production. The jury for the individual categories is chosen from among professionally competent communities and organizations. In order to avoid overly narrow specialization, 300 people involved in the book trade (from university academics to librarians and booksellers) choose the winners in the categories Litera for Discovery of the Year and the Magnesia Litera – Book of the Year. The prize helps people to find their bearings in the sizeable book market. The prize also includes a financial reward of 200,000 CZK (€7,400) that comes with the main prize.

This is the fifteenth year of the Magnesia Litera, and to mark this occasion CzechLit has decided to make the Litera its feature of the month. We are bringing you a brief overview of this year’s winners, an interview with the main organizer, Pavel Mandys, and a selection of the best award-winning books from the past five years.

2016 – A Brief Overview

The Book of the Year was Daniela Hodrová’s Spiral Sentences. Spiral Sentences is an autobiographical novel about the narrator’s sensitively experienced friendship with the writer Bohumila Grögerová and the artist Adriena Šimotová. The Litera jury stated that: “As with the author’s previous books, this work also demonstrates great cultural erudition and an original artistic approach to the form of the novel. In keeping with the book’s title, her sentences develop richly and intertwine into a cyclical and layered story in which the present is permeated by memories, contemporary characters repeatedly encounter the dead, the world of myths is projected onto real events and places, everyday situations alternate with allegorical and dreamlike scenes, and seemingly ordinary things are imbued with symbolic meanings.” Spiral Sentences does not make for easy reading; however, it is all the more impressive for that. So much for the Book of the Year.

The category Litera for Prose was also won by a woman this year, namely Anna Bolavá with her debut novel Into Darkness. Bolavá is an excellent stylist who is able to maintain the narrative pace and keep the reader’s attention. The jury wrote of her book that: “It’s June, everything is in bloom, and Anna sets off into the surroundings on her old bike. The land around her house is full of medicinal herbs. Everything now has to be put aside: memories of her failed marriage, the curious death of her father-in-law, the loss of her job, her troublesome illness. The frantic pace of the harvest is not motivated by the base desire for income; the roots of Anna’s obsession go much deeper. The book has a strange tension; nothing is explicitly stated, so it is up to the reader to find the key. The reasons for the disaster which the main character/narrator is heading towards remain concealed within many portents and episodes.”

And Poetry? Ladislav Zedník was the winner this year with his outstanding collection A City in One Stone. The jury described the book as “the poetic testimony of an adult man, who without showing off and yet with an overview of geological periods, carefully examines his own period, his own life and the lives of his fellow man.”

A selection of the most interesting award-winning books from the past five years

Petr Stančík: Mummy Mill

Ondřej Horák & Jiří Franta: Why Paintings Don’t Need Names

Emil Hakl: A True Story

Kateřina Rudčenková: Walking on Dunes

David Böhm & Ondřej Buddeus: The Head in the Head

Zuzana Brabcová: Ceilings

Jakub Řehák: The Trap for Brigita

Kateřina Tučková: The Žítková Goddesses

Jiří Hájíček: Fish blood

Michal Ajvaz: Luxembourg Gardens

Jan Balabán: Ask Dad

Petr Stančík

Petr Stančík

Mummy Mill

Mlýn na mumie

(Druhé město, 400 pages)

The 2015 Prose winner. Fantasy and linguistic opulence, a post-historical detective novel from the second half of the 19th century. Using several levels of plot and meaning which mirror each other, Stančík narrates a story whose central theme is the relativity of punishment and the way it is carried out. “A very readable story about the hunt for a serial killer set against the backdrop of old Prague,” said the competition jury. Petr Stančík is a middle-generation author, a poet and prose writer, author of children’s books, playwright, advertising writer and essayist. As far as Mummy Mill is concerned, we are definitely talking about an international success; it is going to be translated into Polish, Spanish, Hungarian and Bulgarian.

Praise

“Stančík is simply enjoying himself. His novel is the kind of book that you want to take everywhere and quote enthusiastically from at every opportunity.”

— Boris Hokr, Aktualne.cz

Links

Foreign rights: www.praglit.de

Publisher: druhemesto.cz

An excerpt can be found here.

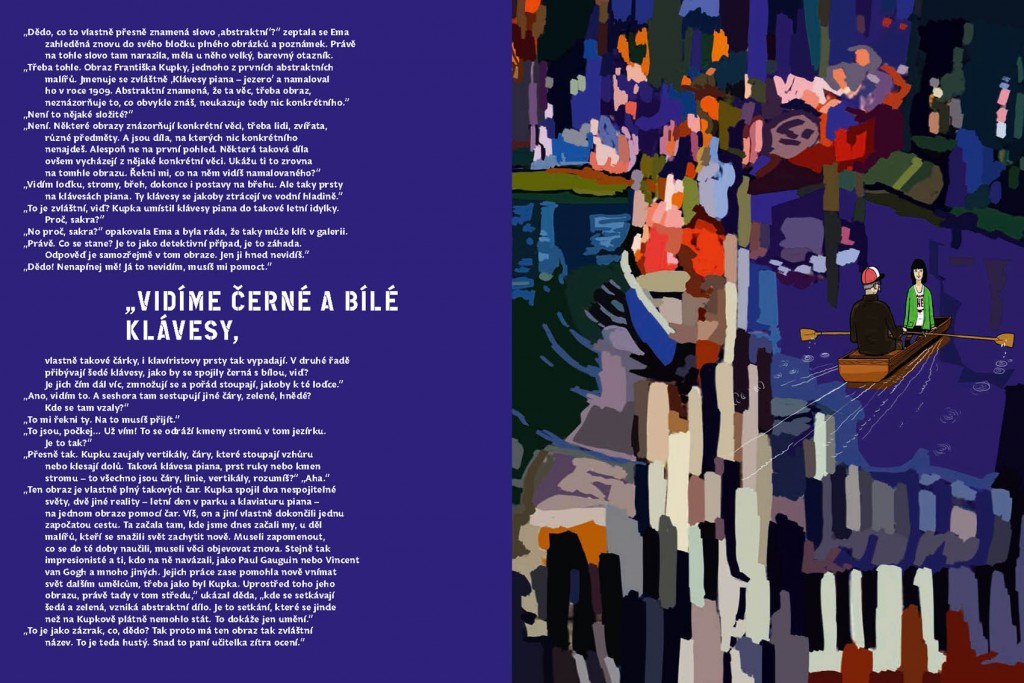

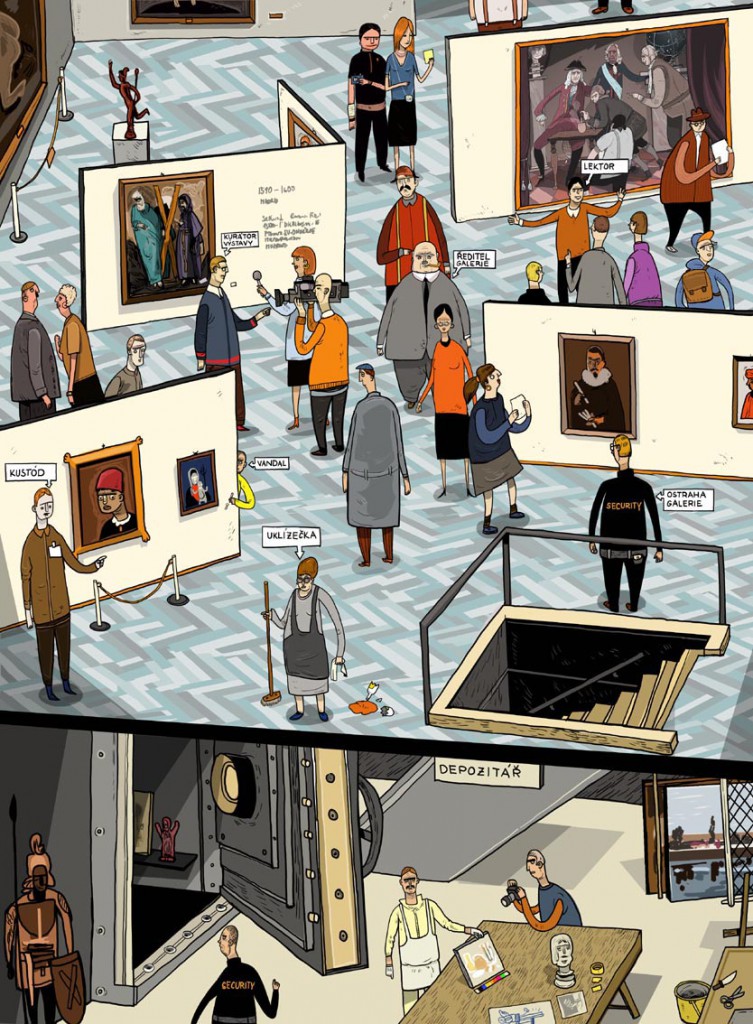

Ondřej Horák & Jiří Franta

Why Paintings Don’t Need Names

Proč obrazy nepotřebují názvy

(Labyrint/Raketa, 96 pages)

One weekend Emma and Nick find out from their grandparents that the world “gallery” applies not only to contemporary shopping temples of consumerism, but also to friendly institutions, which accommodate children’s inherent need to ask, search and think. This Magnesia Litera and Golden Ribbon-winning book uses dialogue-based prose, interlaced with gripping comic-book sequences, to turn exhibition spaces into frolicsome playgrounds that help humanise the forbidding sphere of “modern art”. An experienced advocate of art has joined forces with a notable protagonist of the comic-book circles to create a lovably condensed literary form, combining debates on art-history with light parody and live broadcast of a burglary involving Kazimir Malevich’s famous Black Square. The book includes information summarising main artists, schools, approaches, painting techniques, as well as some of the best-known cases of art theft, giving older school children a better understanding of why an original, and the originality of an artist’s vision, mean so much to us. The jury added: “Ondřej Horák and Jiří Franta have eschewed pedantry and instead gambled on children’s natural desire to ask questions.”

Praise

“This book can be more informative for readers than many general introductory texts about art history or theory.”

— Klára Kubíčková, idnes.cz

Links

Publisher: www.labyrint.net

Illustrations

-

Excerpt ▼

“Granny, how are paintings actually made?”

“It’s quite simple. Artists normally use canvas or paper. But it doesn’t really make any difference – you can use anything you can paint on. You also need to have something to paint with: brushes, paints, maybe an artist’s palette. But you know what? That’s not really important – for example, you can make a picture in the snow with your finger, on the wall with spray paint or on the pavement with chalk. That’s not what it’s about. It’s about what you create. That’s the only thing that really matters.”

“And what about that stand Grandpa has in the cellar?”

“An easel. And a straw hat on your head, paint all over your hands… You know, that’s more just a notion people have about how an artist should look. The truth is that you don’t even need an easel. You can just put the canvas on the ground or on a table. What I mean is: there’s no such thing as the correct equipment or correct appearance for an artist. I know a painter who looks like an office worker, and an office worker who looks like a painter. Just take a look at that painting.”

“That painting’s so big that I can’t look at anything else anyway.”

“Jackson Pollock placed the canvas on the floor, threw away his paintbrush and poured the paint on straight from the tin. He created totally new works of art which continue to fascinate people today, and he didn’t need to have a beret on his head, or a palette, brushes or an easel.”

“That’s cool. But I’m afraid that when I move on from this painting to the next one I’ll forget about it. That after a while I won’t even remember that I saw it and how much I liked it.”

“It only seems that way to you. Powerful things remain inside you forever. And some works of art have that power. You have them inside you and they affect you without you even knowing about it. For the whole of your life.”

“Do you have them inside you?”

“Of course. But don’t think about it as if it was a roll inside your stomach.”

“Hmm, I don’t know, maybe there isn’t enough room inside me,” laughed Mikuláš, and he ran over to the handrail from which you could look down on the floor below and the whole of the gallery.

“You have to believe in it all at least a little bit, as a wise man once said,” added Granny.

(Translated by Graeme Dibble)

Emil Hakl

Emil Hakl

A True Story

Skutečná událost

(Argo, 190 pages)

Hakl is a Czech literary celebrity, best known for his novel Of Kids and Parents, published in ten languages, with a successful film also based on the book. A True Story matches up to the aforementioned book in terms of quality. It mixes snippets from the history of the German RAF with contemporary Czech decadence, an existential thriller with a love story, and grey optimism with black reality. The jury said of the book: “Into the life of a fifty-year-old, dragged down by a safe but dull office job, comes a new woman – and also a new interest in the history of the German RAF. The two central motifs, at least one of which is based on reality, merge and support each other, and from them the author weaves a simple but incredibly powerful story about the moment when an individual finally decides to act.” It has been published in German and Dutch, and a Slovenian edition is in the pipeline. A clear success!

Praise

“Hakl brilliantly describes the world of men who are wasting their lives away.”

— Klára Kubíčková, idnes.cz

Links

Author website: www.emilhakl.cz

Foreign rights: www.pluh.org

Publisher: www.argo.cz

-

Excerpt ▼

The following evening, a cautious knock on the door. Behind it Evžen, closely followed by a tall, long-haired beanpole, bearded and wide-eyed.

Evžen introduces him, “My colleague – a virologist,” sticking out his tongue and pulling a face like a moron, which with him is a sign that he’s ill at ease.

“Could we listen to something at your place?” asks the virologist.

“Why not.”

They sit down by the monitor. No ‘how are you, what’s new’. Straight to the point. Click, click.

The screen fills with a diva plastered in morbid-looking make-up. The notes she’s emitting are hard to describe.

“Those aren’t vocal chords – they’re a grinding machine,” says Evžen’s colleague delightedly. “Oh, yeah! And another thing I didn’t know – in 1977 the paleontologists Adrian and Edgecombe named a group of extinct trilobites after the members of the band: Arcticalymene rotteni, A. Viciousi, A. Matlocki, A. Cooki.”

“I don’t know anything. I don’t watch anything,” counters Evžen. “Last night I put on, er, a classic, Dařbuján and Pandrhola – that’s the kind of crazy fucker I am.”

“Come on, it’s one of the greats.”

“For me it was more about killing time. But I noticed: a – Pandrhola has red hair, b – the evil grain merchant Bašta also has red hair and c – the stuttering doctor who always wants his money up front, otherwise he won’t come, is a bit ginger too. All of the horrible characters are redheads – why is that?

“It makes sense. For two or three hundred years, better-off families would marry among themselves to keep their property together. It started off in the country and then the youngsters went to the towns and immediately got used to life there. That’s why it looks the way it does here. Almost every one of us has an unfortunate gene.”

After that they just silently drink in Diamanda. That’s the creature’s name.

I can’t make them out at all. They know each other from school, from some party. That fiend and Evžen – what can they have in common? Evžen cultivates the hard man image, he likes thrash metal, but other than that he hardly ever drinks, he doesn’t smoke, he’s all about family. He likes to read Ajvaz while drinking tea in the garden. Actually, I guess they took his garden away from him along with the house.

Diamanda produces some screeching which you’d have thought wasn’t human. A belligerent, psychotic shriek.

After an hour I get up. “Guys, I’m off to bed,” I tell them. “There are mattresses and sleeping bags in the cupboard. Tea and coffee are over there, the sugar’s on the table, help yourself to anything in the fridge. Want any alcohol?”

“No alcohol, thanks. Definitely not.”

So you’ve got something, you swine, and you didn’t offer me any. I might not have wanted it anyway, but you could at least have offered.

“I just need to save something,” I say.

“Save away.”

I drop the retching singer into the system tray and back up my files.

They watch me carefully. Evžen giggles in a way that’s typical of him – even he doesn’t know where the funny, clever guy ends and the total arsehole begins. It’s the same with me sometimes – the extrovert wants out and doesn’t know how.

“You’re a total god, the way you’re doing that,” comments the oddball.

When I wake up I can hear a lively discussion next door. “You’ve never been? Never? You have to go there for at least three weeks. Just wander around staring at everything – there’s no way you’ll be bored. Where else in the centre of a city can you see a boar farm, a twisted, rusted factory that hasn’t changed since the last air raid, and a Gothic church occupied by dignified hippies in their sixties trying to be creative but failing because rheumatism and THC have taken their toll. And next to them is a house full of underage anarchists, stinking, gobs of spit everywhere, and their totally vulgar girlfriends.”

“Curty dunts.”

“Yeah, you don’t have to go there. Two doors up there’s a nice little bistro full of eighty-year-old grannies with lace collars – you can chat to them about anything, surprisingly they still have a brain in their head and they’re interested in the world. Of course, it’s normal people who are the most interesting, not those zoological ones, though it’s not so easy to get to them. Not that it’s impossible. You’ve just got to be patient.”

“I’m not, though.”

“You should still go. If you’re coming back by train, take the S-bahn. From a distance you’ll see an unbelievably huge glass ant hill towering above the roofs.”

“I was supposed to have gone for a month, cuntfuck, but I hate always having to push myself forward, trying to get a grant. It’s bad enough that I have to see those grovellers every day.”

“The funny thing is that you can already pick out those types in the first year of primary school. You can see clearly who’s going to spend their whole life in clover and who’ll be in the shit.”

“The most beautiful woman I’ve ever seen was my class teacher at primary school. She had a body like one of those Russian women snipers, hairy armpits… Her name was Rotuše Caltová. When I was falling asleep, I used to have visions of her breastfeeding me, interrogating me and stuff. What ant hill?”

“The Hauptbahnhof. The trains go there along suspended tracks, you go in, you get off. You think you’re in a train station – bullshit, you’re in a shopping centre. Floors and floors of escalators, galleries, one shop next to another. You eat a herring baguette, you gradually go down lower and lower until you reach the bottom. Then you’re in the train station. Aseptically clean platforms, silence…”

I open the door. The same situation. Diamanda is demonstrating the wreckage of her vocal chords.

“She’s chirping like a cicada,” I say and put the kettle on. “Have you been sitting watching this all night?”

“We’ve had enough of her,” confesses the dishevelled fiend. “We’ve been sitting on the floor drinking coffee. We’re not getting in your way, are we?”

Evžen dangles a mug from his tattooed hand, examines the bottom for coffee grounds and smiles ambiguously.

On the table there are 15 empty cups.

Among them is an open tin half-filled with roughly pressed golden-brown pills. They look homemade. They exude a rustic charm. So it’s like that, you fuckers.

I inconspicuously swipe a few of them.

“Time to go,” they get up as if on command. “We’re off. Thanks for the coffee and the digs. Your coffee’s great.”

“Sorry,” says Evžen, “I don’t think I introduced my colleague. We were a bit spun out yesterday. This is Pitvor. I’ll write to you from the fucking corporation. You’ve no idea how those normal emails, where we don’t actually say anything to each other, keep me going.”

His colleague offers me his bony shovel of a hand.

“Pitvor,” he says, “My nickname from nursery.”

“How come you’re colleagues when you both work in different places?”

“It’s not our work that connects us, it’s what we do in our free time.”

And they’re gone.

(Translated by Graeme Dibble)

Kateřina Rudčenková

Kateřina Rudčenková

Walking on Dunes

Chůze po dunách

(Fra, 74 pages)

The winner in the Poetry category. This anthology by Kateřina Rudčenkova (1976) brings together poems from 2008–2011. Eroticism, sensuality, anxiety and loneliness – the ancient themes of poets’ discourse and conversations with the world – sound even more heart-rending and spellbinding in these verses. The book concludes with a captivating cycle of poetry written on the beaches of the Baltic Sahara, among the dunes, in an evocative landscape of deserted grassy plains where one feels as if one is experiencing the end of the world, cosmically and nostalgically. To quote from the jury’s statement: “The poet observes and describes – often so aptly that it sends shivers through the reader… Walking on the Dunes stands up to repeated reading, focusing on the individual layers which naturally intermingle and enlighten one another.” German translations of Kateřina Rudčenková’s poems can be found on the Lyrikline website, and Rudčenková’s earlier collection You don’t have to visit me has been published in German.

Praise

“This new book by the acclaimed poet Kateřina Rudčenková is without a doubt a long-awaited event… As if the moderation of the author’s convictions went hand in hand with a moderation of expression.”

— Michal Alexa, iLiteratura

Links

Author website: rudcenkova.freehostia.com

Publisher: www.fra.cz

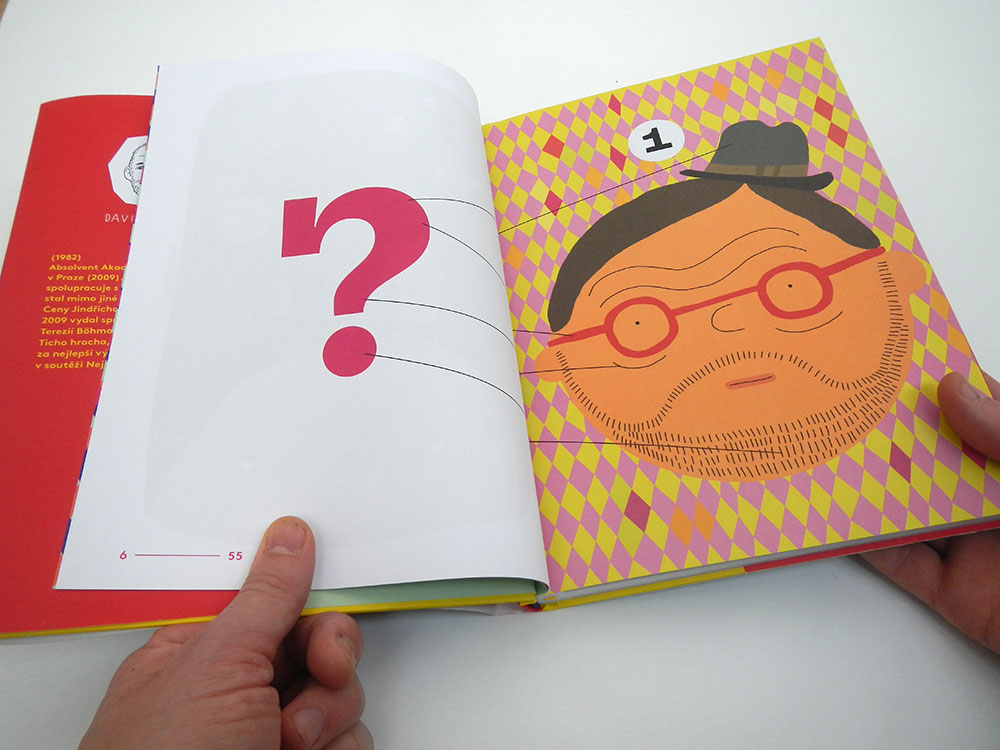

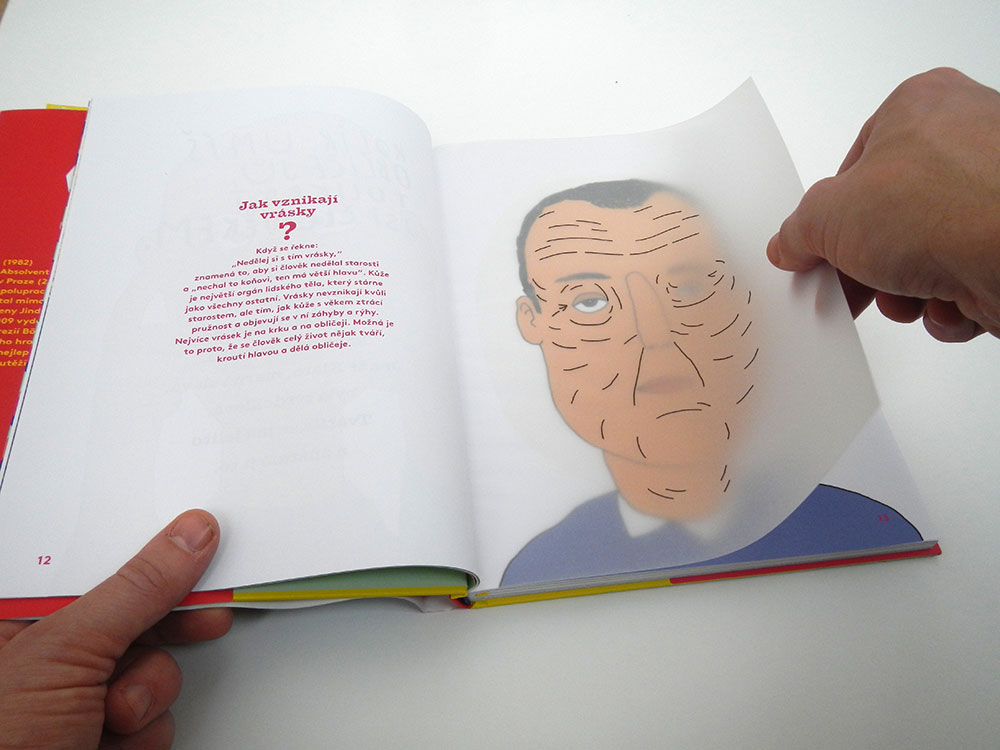

David Böhm & Ondřej Buddeus

David Böhm & Ondřej Buddeus

The Head in the Head

Hlava v hlavě

(Labyrint, 145 pages)

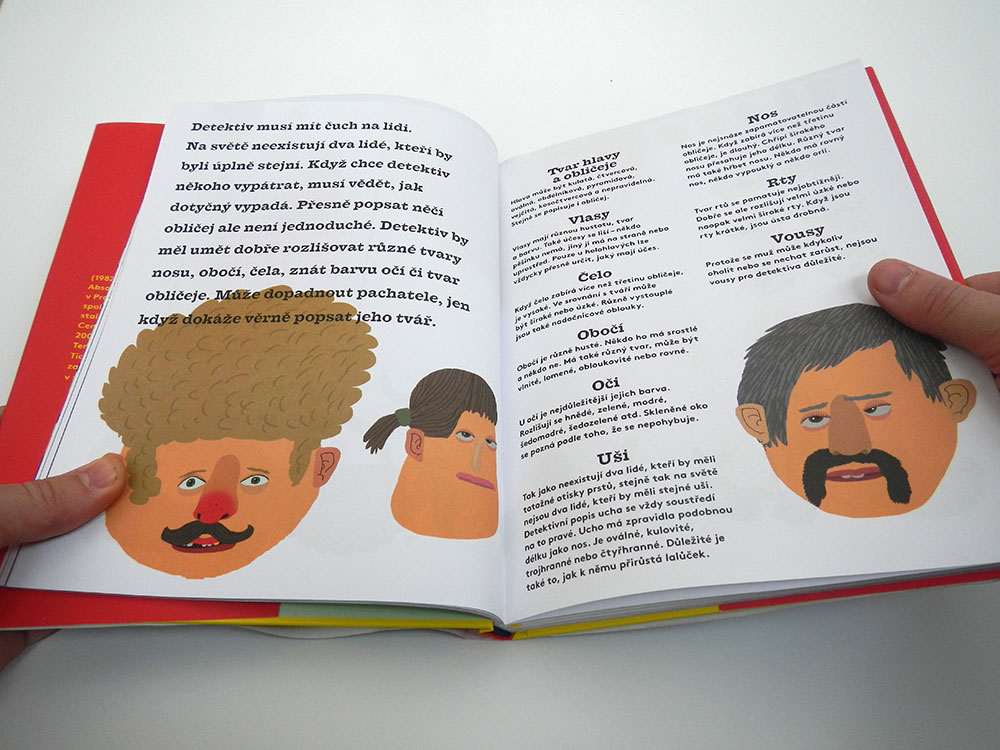

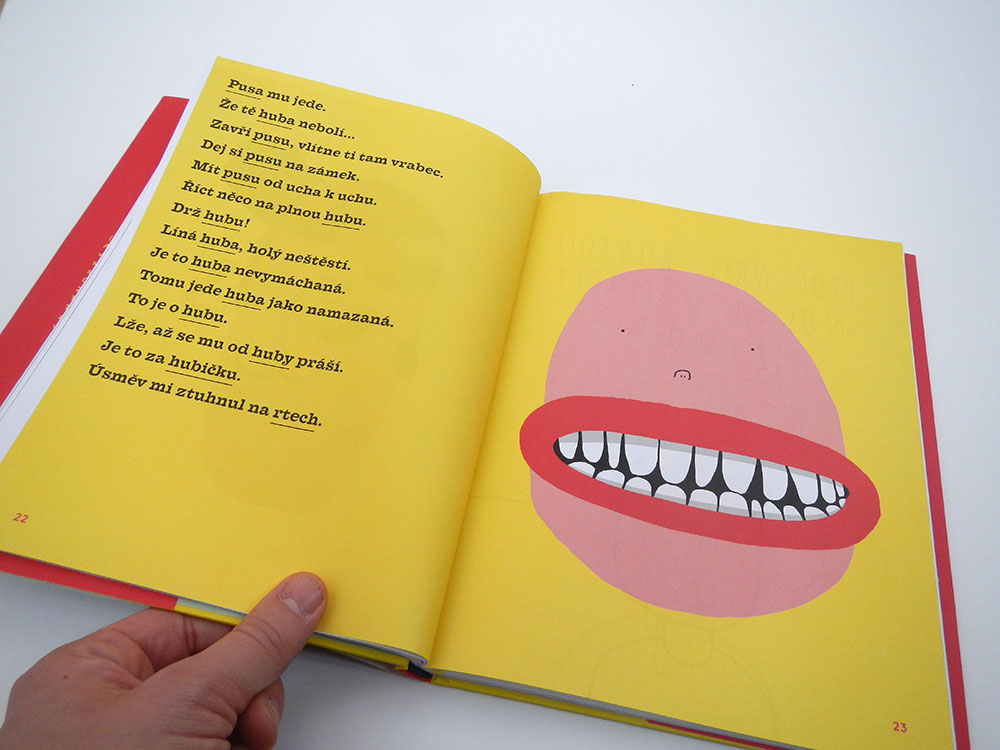

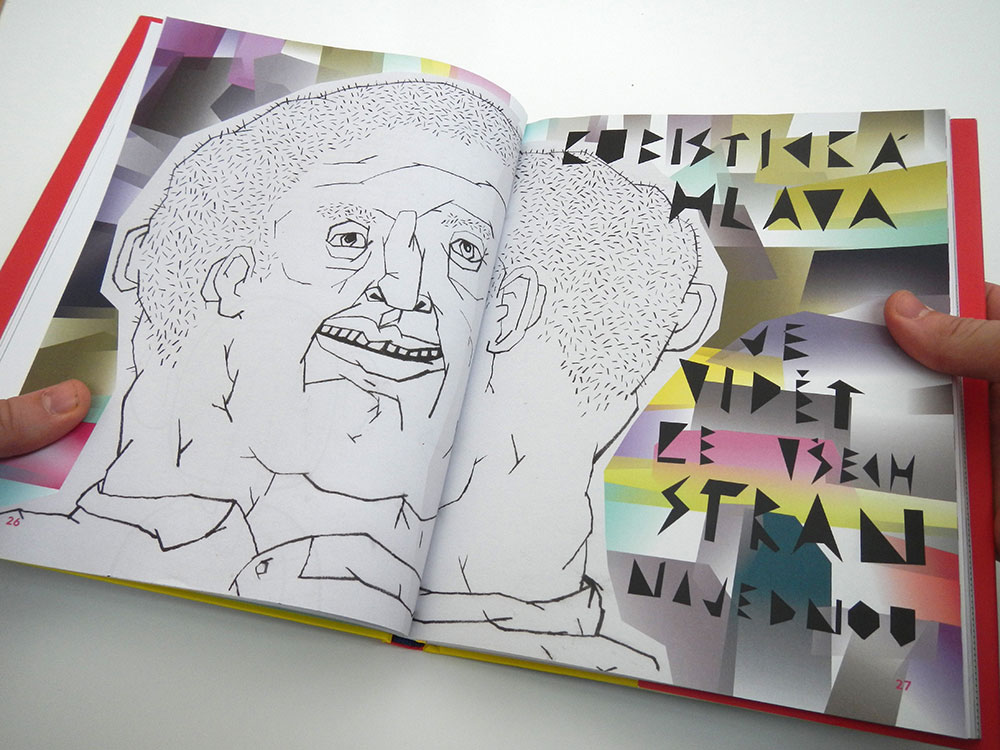

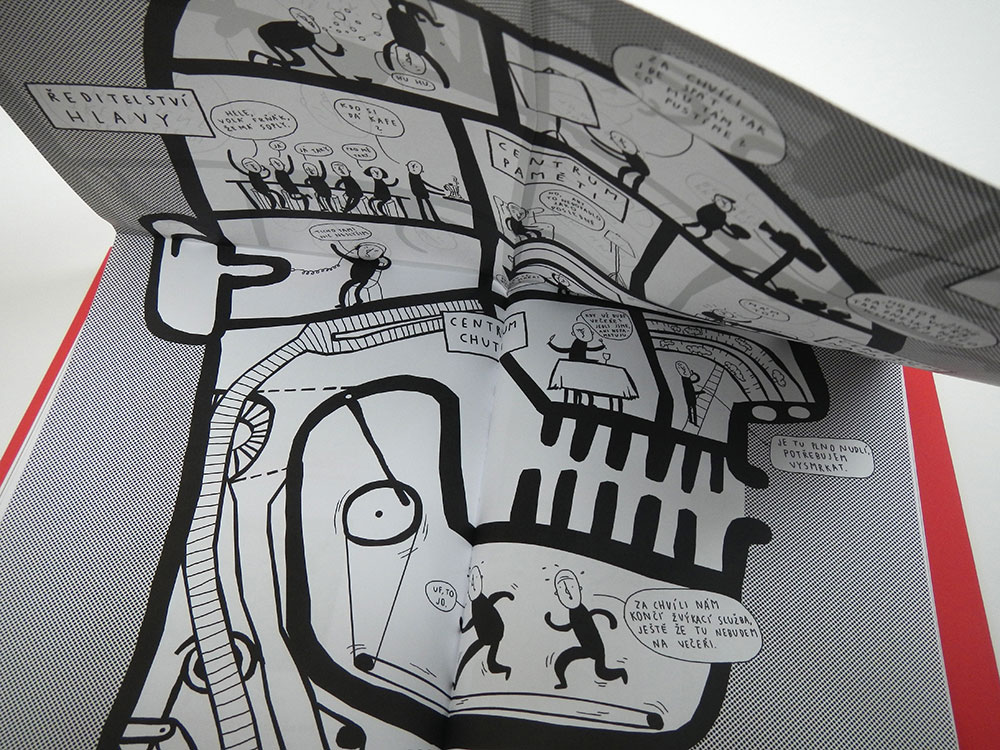

The 2014 Magnesia Litera in the category of Books for Children and Young Adults as well as the 2014 Most Beautiful Czech Book of the Year, followed by the Golden Ribbon in the category of Literature for Children and Young Adults. Few books have received so many accolades. So what’s it about? It’s about the head. The head – that round thing between our ears? Ah, but there’s a lot more to it than that. According to the authors, the head is quite fascinating – it tells us what there is to see and hear, what something smells or tastes like. The head is the management centre of the body because our brain remembers everything – who I am, who you are, and how we can reach each other when we want to put our heads together. In short, the head is the most important part of the body, and the more you look into it, the more you realize that you need at least a small encylopedia to describe everything that is in it and connected to it. The Head in the Head is an unusual and original publication, the first Czech “headopedia”, aimed principally at child readers, which uses an imaginative and playful visual format to help them grasp the basic facts about the head, the brain, and how they work. The result is a visually inventive and poetic book combining humour, fun and information, in which children’s inquisitive questions are answered by, among others, a neurologist, a boxer and a detective. The jury said of the book that: “It is a work which blurs the boundaries of age – similar publications usually boast that they are intended for 9- to 99-year-olds.” A German edition is in the pipeline.

Praise

“The authors have created a book which offers much more than just a few observations about the head and how it works. In 120 pages it demonstrates how it is possible to work with a book as an object. Böhm conceived each page in a completely different way. Sometimes he used simple comic-book-style illustrations; elsewhere he cut out an opening to the next page and Buddeus filled it with stories.”

— Judita Matyášová, Lidové noviny

Links

Publisher: www.labyrint.net

Illustrations

-

Excerpt ▼

THE GIRL WITH A FLASH DRIVE

How Much Can Fit into Your Head?

No-one has yet built a computer which can store as much information as your head does. The human memory is enormous. If someone has an excellent memory, they are not only good at storing but also at recalling information. There are several different types of memory. We have a short-term memory for things that we won’t need to remember the next day. When we are crossing the road, we only need to keep the fact that the green man is lit up in our memory for a few seconds. However, there are some things that we have to remember for a much longer time. Our medium-term memory is used to store information that we will need for a certain period of time, for example at school. We also have a long-term memory for things that we will need to know all our life.

What is the point of forgetting?

So that we feel happy when we remember something again.

How do we memorize something and how do we recall it?

The memory has two important helpers. One of these is our experiences, for which a special structure in the brain called the limbic system is responsible. It recognizes what is pleasant and unpleasant for us and what makes us happy or sad. An experience helps us to remember an event and everything connected with it. It then affects the way we behave in the future. Memory’s other helper is our imagination. There are many different techniques to make it easier to remember something. They all have one thing in common: they teach us how to create a link between what is difficult to remember and what is easy to remember. If you form a surprising, funny or crazy image of the thing you want to remember, then you won’t be able to get it out of your head.

(Translated by Graeme Dibble)

Zuzana Brabcová

Zuzana Brabcová

Ceilings

Stropy

(Druhé město, 200 pages)

Winner in the category of Prose. This novel was the last to be published in her lifetime by the late author of Year of Pearls, an extraordinary novel with an extraordinary theme (one of the first Czech novels to openly describe lesbian relationships). Year of Pearls has been translated into several languages, and Ceilings, which deserves a similar fate, has so far been published in Egypt. The inner drama takes place at a psychiatric asylum; “detox” becomes a place of human relations exposed, a place of torturous questions and answers, a place of life traumas into which the outer world intrudes as an exacerbating element. In an at times fantastic narrative, the so-called real and dream world blend into one, as do the character’s inner feelings and ostensibly objective picture of their lives. The jury said of the novel: “What appeals to readers most is not even the stylistic brilliance. It is perhaps the persistent deliberation upon the fate of a disparate group of sick women through which the author offers us an insight into our equally disparate present. The novel Ceilings seems to confirm the age-old rule that, paradoxically, the more specific a novel is, the more it touches us.” We have to agree.

Praise

“Zuzana Brabcová’s novel is a literary event, a work on the fringes which is extraordinary in its condensed and poetic style. It is, at least for me, the literary event of the past year and beyond.”

— Petr. A Bílek, Respekt

Links

Foreign rights: www.pluh.org

Publisher: druhemesto.cz

-

Excerpt ▼

“Where are you taking me?”

The female nude sprawling in her mass of red hair does not even move. The person has stopped speaking dialect and is once more staring silently at the street in front of him. But then he started yawning so much that the young woman who had been lying down sat up sharply and turned slightly green. Maybe it was because she had been slowly sipping iced mojito. But she had ordered the drink herself! She is sitting with her mother in the cubist café and the waiter is setting two glasses and a cream cake on a little plate in front of them. Naturally, the cream cake is square-shaped – it is a cubist café, after all. Behind the grand piano sits a pianist, and even from here you can hear his joints crack as he wearily runs his fingers over the keys.

“I wanted to talk to you, and now this…” says her mum as the first chords thunder. And I, free of tattoos, sip my mojito and smile because: “Mum, do you hear what he’s playing?” And the worn-out pianist’s voice sentimentally croaks:

Dark eyes, passionate eyes,

Burning and splendid eyes

How I love you so, how I fear you…

Verily, I espied you in an ill-starred moment

And Mum doesn’t believe that it’s just a coincidence, that I hadn’t requested the song from the pianist, and contentedly sinks the spoon into the cream cake…

“Where are you taking me?” She doesn’t shout. She harnesses the roar. She subdues her tone so that she can have a completely ordinary, matter-of-fact, more or less polite conversation between two people. But the ambulanceman was silent. He had even stopped telling jokes about gypsies and poofs to his colleague behind the wheel.

All of a sudden the ambulance stops. A door slammed. For a long time nothing happens.

I dream, though perhaps not about mojito, I wouldn’t dare: they’re going to get me some water to drink. After all, they’re not transporting a thing. A piece of sandstone in slippers. Somewhere in the toilet by the pump they fill a plastic bottle with water and get themselves coffee from a machine, the driver with sugar, the ambulanceman without, and a filled baguette and bacon-flavoured crackers. And now a geyser is gushing from the roadway in front of a car. The cloud bursts above the city and a stream of water goes straight into my mouth. Down at Můstek, three fat, smiling, chattering old Italians lean over to drink on a hot summer’s day, 16 July at 1.15pm in the year 2008. Or some other time? Does it matter?

I place my palms under a gushing spring somewhere high in the mountains – you are with me; I follow your bent, girlish, delicate back and your firm, non-girlish step which says: Christ, stop lazing about all the time in bed with your depression and get up and walk, go, stride, plod, march, slog through the countryside and scramble your way up the hill and run down the hill, breathe deeply, like Mum used to tell you when you were a young girl, Jesus, you’re breathing like you were giving birth, you have to breathe deeply!, inhale the fragrance, look at what’s rustling behind that tree, an animal or a rock, over there’s a dilapidated hide and underneath it is a boletus mushroom, when was the last time you found a real white boletus?, and the wind in the trees and cobwebs between your fingers, and on your shoulder a mosquito sits in a drop of your blood.

And you let me drink from your cupped palm – not much of a success, I just get a wet face. We still have ten kilometres ahead of us and my feet are covered in blisters. Suddenly, down in the valley below us, the landscape forms a dome, glowing in the setting sun. I embrace you as if it were for the last time. Where is that moment? Who could find it in my body, now as stiff as a statue? Where is that moment…who could find it…and your tongue in my mouth, the taste of blackberries, your saliva, life.

Finally. The redhead opened the door and banged it shut again. A man in a leather jacket slid into the seat beside her. Thick plastic glasses jutted out from his face. He looked a bit like Andy Warhol.

“Do you have anything to drink? I’m terribly thirsty,” she whispered when they started off again.

He barely glanced at her. He probably just registered with indifference the sedated monument with purple slippers on whose belly a knapsack had lain since the year dot. In her haste she hadn’t been able to find anything else in the box from Popel. He averted his gaze and didn’t say a word.

Wherever they’re taking me, Rybka, I’ll make up for what I’ve done to you: I’ll roam the hospital corridors and let them shove a hosepipe into my bowels and at night I’ll cover myself up with the mumbling of sick old people and their children by their stinking beds, children sickened by the time wasted in the disgusting hospital stench, I’ll let it all into my head as penance for the unfathomable babbling of the world and the rasping shriek of goblins.

Behold, just see how I come into the prison courtyard, dizzy and tired, and dribble sauce from a mess tin onto my sweatshirt, and how the hungry hands of thieves grope me at night; I throw myself into prayers, as cold as the river Vltava in January, or I will be forever immobilized in a bubble of silence; and then, thrusting, lying down and standing up, standing up and lying down, I walk round Mount Kailash, above which circle vultures and at the foot of which your grandfather wanted to be chopped up when he dies.

Anywhere, just not to the Garden.

And once again they’re rattling their way through the city over the cobbles, over the asphalt, and they stop at the traffic lights. At one point Ema turns onto her side, as far as the straps will allow, and vomits. She vomits under Andy Warhol’s feet. A small jellyfish glistens on the ambulance floor, a cartoon bubble that they forgot to write text in.

“Do you want to play Chinese Whispers with me,” she asks. But Andy doesn’t understand. How could he? It’s impossible to play Chinese Whispers with only two people. And so she starts to play by herself, she whispers and mutters, stutters and then passes it on, and then it suddenly hits her, what if at least once in this game it was the other way round – what if in the end a clear word formed from what had started off as a piece of nonsense: for example –

Garden. She can see it wildly pulsating, as if they had just created it a second ago, that mockery of symmetry, the monstrous cosmos split into a triptych. Around a well, into which clusters of dead birds rain down, naked riders on pigs gallop through a dark landscape shot through with flashes of light; the pope-devil on a magnificent throne devours and then immediately throws up the damned and at that moment there is dancing to hellish music and a goblin with a drum in which an infant is trapped, and over here scorpions and a man crucified on a harp, and over there two ears joined by a needle, from which the handle of a knife sticks out.

“The pope-devil there is devouring…” The glasses turned round to her inquisitively. “Do you know where they’re taking us? Do you have anything to drink?” And surprisingly Andy Warhol says something. “I’ve no idea. I imagine you’re cold.” And Andy Warhol takes off his leather jacket and covers her up to her chin with it.

The ambulanceman says something into the radio. Only then did she realize that the siren wasn’t switched on. Fortunately neither she nor Warhol were at all important. Not acute cases. She should have tried to leave the emergency room at Motol on her own, leave an empty wetsuit there in her place, swim home and fall asleep, without any tablets this time, sleep for twenty-four hours and then wake up, open the blinds and go to work and have lunch with Rybka and light candles in the evening, and put on Nico and wait for Dita to call… And talk to her and laugh and then make love at night. Wake up. Open the blinds. Go to work. Call Rybka, invite Mum for a mojito and a cubist cream cake at the café. Simply keep moving in the safe womb of everydayness.

(Translated by Graeme Dibble)

Jakub Řehák

Jakub Řehák

The Trap for Brigita

Past na Brigitu

(Fra, 80 pages)

Winner in the poetry category (2013). Jakub Řehák was born in Uherské Hradiště in 1978, graduated from the post-secondary film school in Zlín and now works in the Municipal Library in Prague. Besides poetry, he also writes essays. He builds on the avant-garde of the First Czechoslovak Republic, particularly the legacy of surrealism that he brings up to date in an original way both through a distinctive vision of cinematic editing and through a captivating expression derived from the Apollinairian concept of a poem as an unbound ‘zone’. Brigita, the titular character of the book, is not only a specific girl, the poet’s lost lover, but also a common, slowly uncovered feminine principle. The jury said that: “Řehák’s poetry is a gripping stream emanating from a confident poetic gesture through which the poet recasts raw ‘signs of the times’ into an unsettling and purely contemporary myth.”

Praise

“This is poetry which opens up gradually, which one enters into in a roundabout way. Poetry which knows how to snap its trap shut even when it is read repeatedly – and each time with the help of a different lure.”

— Markéta Kittlová, iLiteratura

Links

Publisher: www.fra.cz

Kateřina Tučková

Kateřina Tučková

The Žítková Goddesses

Žítkovské bohyně

(Host, 456 pages)

Kateřina Tučková is an art historian, translator and writer who has been very well received by Czech readers over the past decade. Her best known novel, The Žítková Goddesses, sold over 110,000 copies, won four Czech awards including the Magnesia Litera Readers’ award and has been translated into many languages including German and Polish. The novel is a fascinating tale of the female soul, magic and a part of Czech history kept hidden. A group of mysterious woman, known as goddesses, have lived high up in the White Carpathian Mountains. They are far away from everything, which is why it is said that certain women among them have succeeded in preserving knowledge and intuition the rest of us have lost. They have passed this knowledge down from generation to generation for centuries. Dora Idesová is the last of the goddesses. She is reluctant to accept an outdated way of life and to read the futures of those who come to her in drips of wax, as her Aunt Surmena did. But everything changes once she understands that her personal circumstances that she has always considered unhappy – being sent to a boarding school and hospitalization in an asylum – is part of a carefully thought-out plan. It is the late 1990s, and in the archives of the Ministry of the Interior there is a file awaiting discovery – a file compiled by the State Security police on an enemy of the state, her Aunt Surmena. A disbelieving Dora begins to untangle details of the previously unknown fates of her family and other goddesses…

Praise

“A brilliant mix of fact and fiction.”

— Der Standard

Links

Author website: www.katerina-tuckova.cz

Foreign rights: www.dbagency.cz

Publisher: nakladatelstvi.hostbrno.cz

An excerpt can be found here.

Jiří Hájíček

Jiří Hájíček

Fish blood

Rybí krev

(Host, 360 pages)

Hájíček is from South Bohemia. In Hájíček’s case it is worth mentioning this geographical location – not because he is an author of purely local significance (on the contrary – Hájíček is one of the Czech Republic’s finest), but due to the fact that he uses this setting as a theme in his books. He has won two Literas: the first for Rustic Baroque, which has also been published in English: however, we wish to draw attention to his other prize-winning book. In 2008 Hana returns home to the village she grew up in after 15 years abroad. But the place she had imagined settling in, marrying and working as a schoolteacher has become a virtual ghost town. The story revolves around the building of the Temelín nuclear power station, which involved clearing several villages. Their displacement severed old ties and roots. Seeing her father, brother and childhood friends Hana takes a searching look back and tries to heal old wounds. The jury stated that: “A power station and the residents’ futile struggle against it becomes the backdrop to dramatic interpersonal relationships and stories of ordinary people in unusual circumstances, narrated in a traditional manner. The author describes the plot and characters vividly and convincingly, creating a high-quality work of literature through his simple style.” It has been published in Polish, Hungarian, Belorussian and Bulgarian.

Praise

“With Fish Blood Hájíček has become a master of intimate drama. The ordinary and everyday are vivid in their effect; the blend of detail is altogether plausible. At the same time the author’s informal style – no strained metaphor or affected layering of semantic imagery as freed by the postmodern imperative – always succeeds in creating the right atmosphere. ”

— Eva Klíčová, Host

Links

Author website: www.hajicek.info

Foreign rights: www.dbagency.cz

Publisher: nakladatelstvi.hostbrno.cz

An excerpt can be found here.

Michal Ajvaz

Michal Ajvaz

Luxembourg Gardens

Lucemburská zahrada

(Druhé město, 176 pages)

Ajvaz is a poet and novelist whose books can be classified as playful literary fantasy filled with symbols. His books are regularly published abroad and have been translated into English. The French translation of Ajvaz’s The Other City was awarded the Utopiales prize for science fiction. The novel we have selected was awarded the Litera for Book of the Year, and also contains elements of science fiction. The Luxembourg Gardens describes a sequence of events experienced by Parisian secondary-school teacher Paul in the summer holidays. In an absent-minded moment he hits the wrong key on his computer keyboard and misspells a single word; as a result, he spends the happiest and most terrible period of his life. The action of the novel is set in Paris, Nice, Nantes, New York State, Moscow, the Caribbean island of Saint Lucia, Taormina in Sicily, and Lara, a town of the author’s invention. It has already been published in Russia and Croatia, and preparations are underway for a Bulgarian edition. The jury stated that: “The author manages to do something simple yet quite remarkable: he perceives his mother tongue differently, as if from the outside, and penetrates into its very essence. He sees its hitherto unnoticed, miraculous qualities; he senses its melodies and hues. This idiosyncratic linguistic obsession leads to knowledge. The novella is not as sophisticated as Ajvaz’s previous books – with one difference: there is a sophistication here in the intermingling of subtle prose with elements more typical of lower forms of literature.”

Praise

“In his latest novel, Michal Ajvaz has ingeniously built up an incredibly imaginative web of stories which connect up, cross over and influence each other.”

— Markéta Kittlová, iLiteratura

Links

Foreign rights: www.dbagency.cz

Publisher: druhemesto.cz

An excerpt can be found here.

Jan Balabán

Jan Balabán

Ask Dad

Zeptej se táty

(Host, 192 pages)

This novelist and translator is one of the best and most popular writers of the past two decades. His most highly acclaimed work, We Might be Going, was named Book of the Decade in the Magnesia Litera competition. The book we have chosen won Book of the Year in the same competition, as well as the Lidové noviny newspaper’s Book of the Year and Respekt magazine’s Book of the Year. The crux of Jan Balabán’s novel focuses on dying and death even though its inherent plot centers on the painstaking pursuit of life, which first has to be found in its depth or reinvented. In a sense, we are all somehow similar to the characters of this extraordinary, vibrant story replete with dialogue, soliloquy and silence. A story which searches for truth only to find sincerity. In our temporal existence, we are trying to discover something about the quintessence of actuality or be near – at least momentarily – to something substantial. It has been published in Sweden and Poland, and Bulgarian and Serbian editions are in the pipeline. The jury stated that: “Balabán’s latest, almost chilling, novel is an incredibly honest account of life in extremis.”

Praise

“Ask Dad, which Jan Balabán spent the last three years of his life working on, is the essence of his writing: it is autobiographical, harrowing and depressing. It tries to come to terms with the past and the future. It is gripping, economical and authentic.”

— Kateřina Kadlecová, Reflex

Links

Foreign rights: www.pluh.org

Publisher: nakladatelstvi.hostbrno.cz

-

Excerpt ▼

Get up early. Outside the window the blue ink of a night already fractured into day. It happened just a short while ago. How I’d like to be there again some time to witness our terrestrial floe passing out of the realm of night. Seeing this means not going to bed at all. Sitting by the fireside all night. Occasionally throwing on another log. Occasionally uttering a few words and then just wearily observing the darkness growing thinner among the trees. The grey of the trunks transforming into the first hint of colour, blue smoke from the fire, and then you look around and everything is naked in the first light of day.

Sometimes you can’t sleep. But insomnia isn’t the same as being awake. It is a horizontal neurosis. A torturous kind of hoping. An urgent expectation that at this very second of waiting for sleep, the longed-for sleep will come. That second stretches out into an unbearably long, unbroken period of time. Like the moon tonight. It stole into the window pane from the left-hand side an hour after midnight and slowly made its way across it in a descending, flattish arc until five in the morning, when it disappeared beyond the right-hand window frame. If I had been asleep, I wouldn’t have seen it at all. If I had stayed awake and looked up from my work or my book from time to time, I would have seen its disc at various points along its path. But insomnia drew its entire course out for me like the trail of a silver slug upon dark glass. For an undivided five-hour-long instant it showed me how the world smudges into blurs and the universe into slug trails when a moment cannot come to an end.

Hans thought of his father, who suffered from insomnia during the last few years of his life. The stress of the hospital, of the pale, sickly faces and the fates of people dependent on machines. Later came his own cardiac arrhythmia, prostate and above all anxiety. Whether Kateřina would ever overcome her illness, whether his two boys, Hans and Emil, would make something of themselves or would squander their abilities and drink themselves stupid, as now seemed likely. Whether his wife Marta would be happy one day or would just have to go on and on putting up with things. Whether this whole life that we crawl through like soldiers in the mud under barbed wire was futile. Whether this burning and cramping up would one day pass. And whether we would ever meet our parents and brothers again, whether we would be united, at least through our destiny, at least through the same love at various times, until time ceases to exist. Is there a fellowship of the living and the dead, as children have been told so many times? Or is life just burning and cramping up, just a meaningless blur, the trail of our spiritual and biological decline?

And so Hans got up early. He just threw a sweater over his pyjamas, slipped his bare feet into his shoes, let the dog out and went to take a leak on the field in front of the hut. I’ll go round the corner and I’ll see it among the boughs of the fruit trees, big, much bigger than in the night, and white like a temporal bone. A perfect circle. No, it isn’t perfect, it’s already waning and it’s flattened on one side, which makes it look all the more like the human skull that my brother Emil showed me sticking up out of the ground from a dug-up grave in the town cemetery. At the time Emil was working there as a labourer. If he couldn’t study, he could at least come up with a bizarre manual occupation for himself. Sleep, he said then, contemplating the skull through narrowed eyes, is a landscape of its own. Then he handed the skull over to the gravedigger, who wrapped it in a black rag along with the other remains of the grave’s previous occupant and laid them to one side.

Hans went into the hut. He threw a handful of kindling onto the last glowing coals in the stove. It roared cosily for the first time since evening. He put water on for coffee and went to take another look at the moon in the branches of the fruit trees, at that image which would be so difficult to paint with all the connotations it had now. It was even bigger, closer to the horizon and much paler. It was dissolving in the early morning like a sugar cube.

Am I a sleepwalker? Hans asked himself, gazing in fascination at the temporal bone among the leafless boughs and moving back through the tunnel of time. A few years ago at six o’clock in the morning the same bone had been hanging among the antennae on the roofs of the blocks of flats by the hospital. He had only noticed it when he switched off the car lights in the car park in front of the main entrance. He had come for his dad, who had called his mum to say that he had started to feel unwell while he was on night duty, that she shouldn’t worry, that he would just go for some kind of examination in the morning to rule something out. And his mum had immediately called Hans and asked him to go and collect him, because she often had hunches which were regularly proved right, and so Hans went immediately.

He looked at the moon impaled on an antenna and asked whether it was a good or bad omen. Was he here too early, or had his dad been delayed? He hadn’t. He was walking slowly alongside the wall, with one hand on it for support and the other clutching his stomach. It was really him. Now he had both hands on the wall, as if he was afraid that he would fall, and in this cautious way he proceeded by sidestepping along the length of the wall towards the main entrance. He was on his way back from somewhere, probably from a futile attempt to get somewhere by himself. The early-morning walkers cast disapproving looks at him. They thought he was drunk. Hans ran up to him and supported him.

Dad, what’s going on?

I seem to have got a bit mixed up, lad. I wanted to go home, or to neurology or somewhere, but now I’m wandering around in circles. I imagine I’ve had some kind of episode. Some kind of minor stroke. After that people get confused like this.

Where do you want to go? Should I take you to neurology, or home?

Home? All the future events of his life were contained in the look he gave me. We can’t go home like this. I have to go to the hospital.

But you’ve finished your shift. I’ve come to get you.

I know. You’re a good lad. But you know, son, I need to go to the hospital now, not as a doctor, but as a patient. First I need to go to neurology. It was probably an ictus. Take me to Dr Skála on the second floor. You know him, Petr Skála. He’s got the same first name and surname.

How’s that?

Peter, you are my rock. Skála – rock. That’s what I meant – from the Bible, you know?

Of course I know.

So take me to him and he’ll check me over. And then we’ll go through all the steps until we figure it out. First we have to rule out…

The mournful expression that my father had had in his eyes at the mention of home was gone. Dr Nedoma had begun to matter-of-factly review the case of a patient who happened to be he himself. And, supported by his son, he walked as a patient through the doorway from which he had emerged as a doctor for the last time a short while before.

Someone tugged at Hans’s sleeve. Hans opened his eyes. It was a dog. As if to say: Don’t sleep. The kettle on the stove had almost boiled dry. Dark sky beyond the window, just a light streak above the horizon. Was it evening, or morning? At that moment you couldn’t tell. It would depend on what came next. Then that arrow would appear, that accursed vector of time. The way it did then, in the moment between the doctor and the patient. Not even they could remain standing in that doorway for ever.

(Translated by Graeme Dibble)

[ ]